For the past few weeks, Iron Halo, a catalog of Sal Salandra’s art, has occupied my coffee table, stopping everyone who sees it in their tracks. The cover is a detail from a work called Human Ashtray: an ultramarine background surrounds a bearded man wearing a dog collar, his head restrained by a disembodied hand. Two cigars flick ashes into his salivating mouth. But it’s not the shocking nature of the picture that commands a double take—the real reward arrives when you notice that the image is composed entirely of cross-stitched thread.

Salandra, a septuagenarian artist with no formal art education, has practiced needlework for more than four decades. At first, he created quaint pictures of dogs and flowers while working as a hairdresser, but for the past 10 years, he’s been crafting complex, provocative, sexual and sometimes absurd scenes reflecting queer subjectivity, BDSM power dynamics and the debauched underbelly of Catholicism—all things with which he is intimately familiar. Iron Halo captures the work Salandra exhibited at his first-ever solo show in 2021, hosted by Club Rhubarb, an experimental gallery run by Tony Cox out of his Chinatown apartment in New York City. As the catalog’s introductory essay by Michael Bullock notes, Salandra, a longtime member of the leather community, sees a connection between Catholic pageantry, acts of submission that permeated his youth, and the rituals surrounding BDSM that liberated him as a gay man later in life.

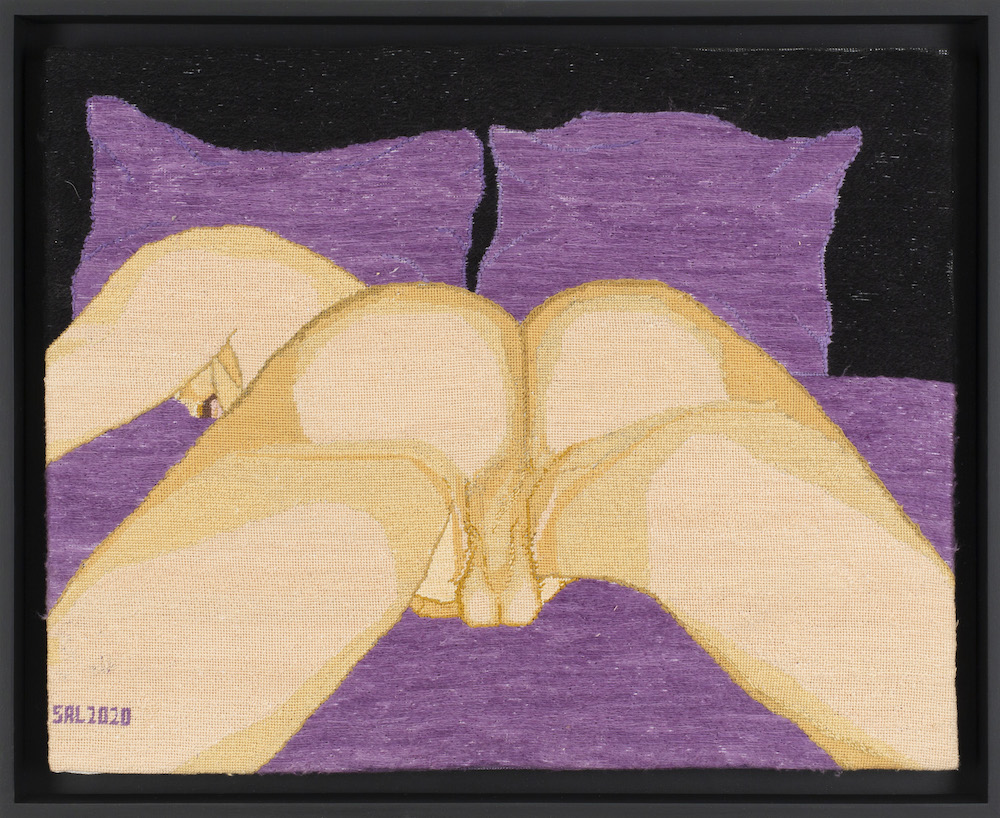

Kiss It, 2020.

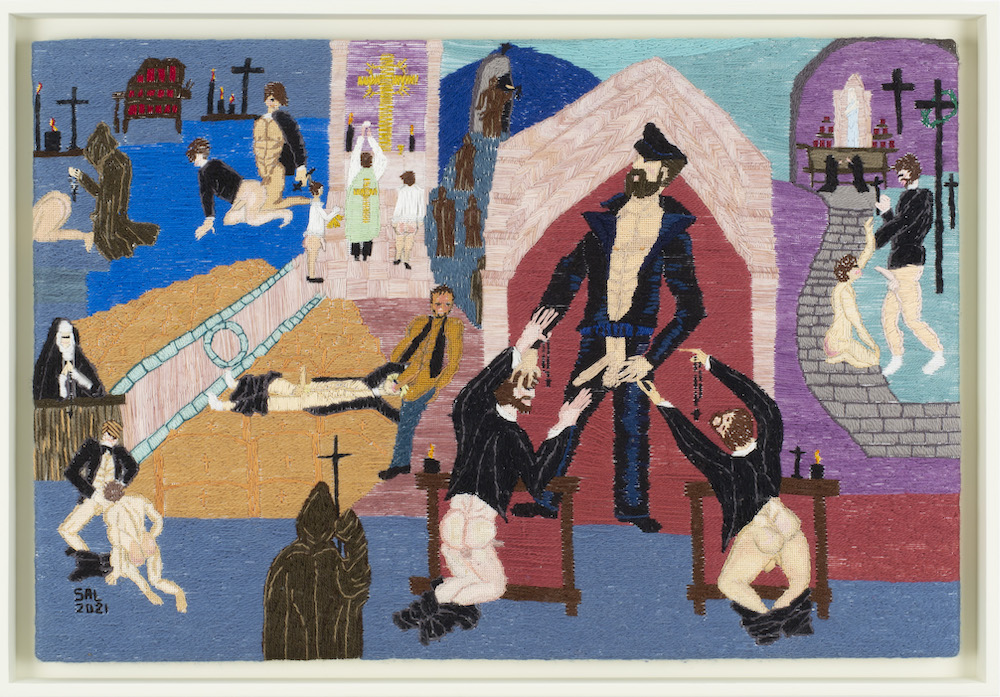

In Church Taught Sex Is A Sin, we are drawn into a multi-perspectival narrative within the confines of a sacred interior. A hooded figure watches the scene unfold as two bare-bottomed priests kneel in prayer, clutching rosaries as they reach toward the cock of a ripped leather daddy who stares into the distance at the blessing of the Eucharist held aloft by another priest, attended by altar boys with reddened backsides. Nearby,

another priest lays on the ground as his mouth vacuums up the crotch of a man wearing jeans and boots. And there’s plenty more action in the rest of the image—an orgiastic ballet straddling sin and salvation is brought to life through painstakingly stitched threads, forming a delicious dialogue between technique and taboo.

The subversive power of Salandra’s art depends on its ability to catch its viewer off guard while celebrating libidinal exuberance through a traditionally conservative medium. Needlepoint typically adheres to predetermined patterns and predictable outcomes along a rigid grid, contributing to its associations with order and control. But Salandra’s work, which he calls “thread painting,” ventures into improvisation, often taking on the more ornamental appearance of embroidery, using threads as brushstrokes to evoke tactile elements, from body hair to veins on an engorged phallus.

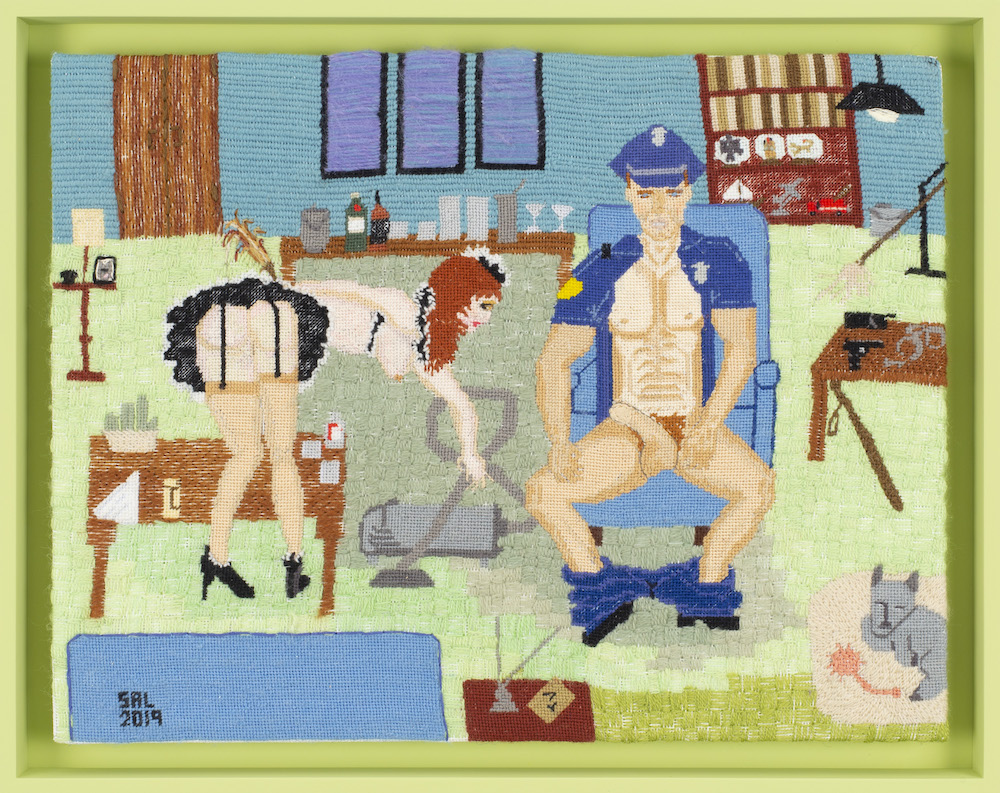

Maid Service, 2020.

While Iron Halo doesn’t delve deep into art-historical precedents, one can’t help but place Salandra within a long tradition of needlepoint. Since the Industrial Revolution, the discourse surrounding this craft in the Western imagination has hinged primarily on its associations with femininity and domesticity, which until recently relegated it to the periphery of “serious” art. Generations of artists have worked to contest, subvert and queer these presuppositions, using needlepoint, embroidery and weaving as critical vehicles for counter-narratives—a way to highlight the thoughts and actions that “polite” society hides away, or actively tries to erase. Salandra’s practice comes in the wake of such mid-century artists as Allen Porter and George Platt Lynes, whose modernist creations explored homoerotic themes that were more palatable in their era.

Salandra’s work also stands out from other contemporary artists who use needle and thread to directly reference sexually explicit subject matter. Take Leah Emery, who makes complex, thread-bound images reproducing stills from pornographic films. Her work creates meaning by juxtaposing the cross-stitched canvas with the glossy sheen of porn, complicating gendered associations that permeate the two. Salandra’s work operates more viscerally. Filled with awkwardly rendered bodies and flattened picture planes, his thread paintings reflect the uninhibited style of an

“untrained” artist while also producing a surprising sense of immediacy and spontaneity that we don’t normally associate with needlework. This removes any tinge of irony or associations with the countless cross-stitched naughty schlock items you can buy on Etsy.

One of the best aspects of Iron Halo is its use of conventionally photographed images of the artist’s works alongside full-bleed spreads that highlight details of specific pieces, allowing readers to fully appreciate his laborious process. The book provides an intimate interaction with the work, creating an experience that surpasses seeing it on a digital screen (though Salandra’s website is filled with astonishing art). Although it is a slim volume, containing only 14 thread paintings from the artist’s growing oeuvre, Iron Halo leaves an indelible mark. I pray there are plans to publish his catalogue raisonné in the near future