Installation—often understood as the act of locating, positioning and inserting—has, in Nari Ward’s exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch gallery in Los Angeles, intersected with the examination of founding American democratic principles. This combination of past works and contemporary gestures instigates a conversation about the reality of the Westernized world view and its attendant assumptions—plantation, colonization and annexation.

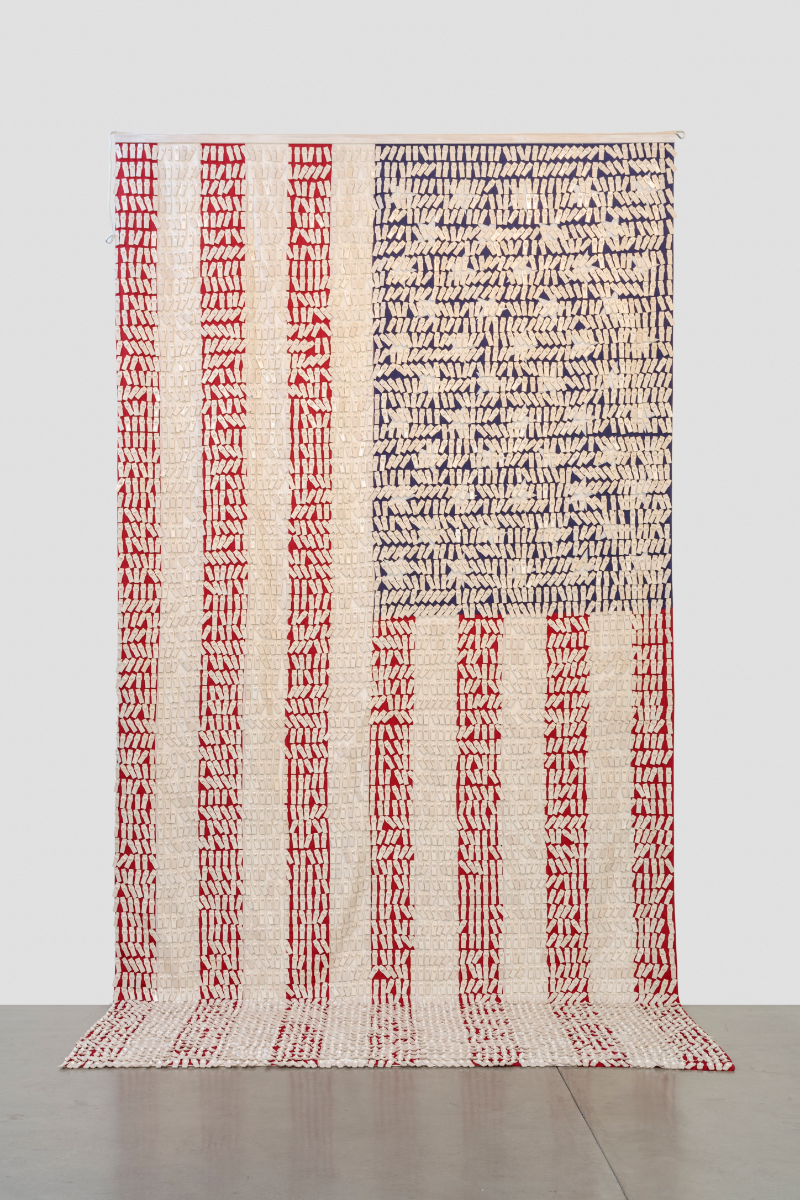

His work Say Can You See (2021), also the title of the exhibition, shows commodified surveillance disguised as freedom as it waves its message. Its title borrowed from the first stanza in America’s national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner (1814), foreshadows a visceral dialogue with viewers. Studded with 6000 white plastic security tags, a towering American flag drapes against a wall and cascades along the floor toward the viewer, suggesting that there are those who are waved to enter and others who are stopped at the door. In light of the January 6, 2021 insurrection and storming of the nation’s Capitol, Ward’s material is a thematically potent choice. The connotation of white security tags evokes safety and protection while simultaneously questioning historical privilege connected to the social construct of whiteness. Like such contemporaries as June Edmonds, whose acrylic Allegiances and Convictions paintings series (2018-19) reinterpreted the meaning of this patriotic symbol, and Rodney McMillian’s mixed-media work, Flag (2002), Nari Ward contributes to the discourse surrounding Old Glory as artifact and artifice.

Nari Ward, Say Can You See, 2021, 1995. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles.

Roll Jordan Roll (2021) references the name of the 19th century black spiritual sung by enslaved Africans who worked on plantations in Southern states. Written by the English cleric Charles Wesley, the popular song was used as a colonizing tool by white slaveholders, compelling their chattel in conversion to Christianity. It was instead subverted by the enslaved as a weapon of agency. Using shoelaces like hanging needlepoint, Ward has written the song’s title on the wall, and the billboard appearance begs to be read. The laces, dripping like Spanish moss from the Southern live oak or the Italian cypress, sadly summons another song, “Strange Fruit” by Billie Holiday where she sings of the horrors of lynching.

Employing oven pans, ironed cotton and burnt baseball bats, Ward has assembled Iron Heavens (1995). Appearing like a sacrificial altar to be wept over or worshipped at, this installation speaks of servitude and violence, as well as sports being a cultural metaphor for war. After all, in baseball there are winners, losers and cheaters. Meticulously laying the bats in groups like rifles against the square iron wall suggests that the game is over. But racism in America is always a double-header.

Ultimately, Nari Ward’s body of work initially entices then provokes, asking us to see beneath and beyond what society has been taught to say and we taught to believe. Each work is unflinching in its aggression. Ward’s message invites receptive viewers to repeat what James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond composed in the Black National Anthem: Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us.