The hair of human beings has a significant amount of lore associated with it throughout time because it is such a highly symbolic part of the body. Hair has had great social, cultural, and economic meaning and in every moment of that history the visual arts have registered the role hair played in the story that it was framing. Hair can be styled, it can be removed, and it can be modified by color or organized by the type. It has been regulated, governed and used as a tool for creating and modifying identities. Nancy Buchanan has been working with hair and images of hair since the 1970s and “Crowning Glories” details her ongoing explorations ranging from primarily performative instances to more drawn and sculptural works.

In the seminal work that lays bare some of the contradictions she explores, A Little Style (1975), the artist staged a performance in which she and a group of five women occupied a semi-public place. The performers and an audience inside the Wilshire West Plaza participated directly while passersby on the street could follow the performance through the large picture windows. To begin, Buchanan did a little dancing while facing the audience and the outside. The other five performers who were facing away from the street, each read about a difficult childhood experience while the artist tried to arrange their hair into different geometric compositions. Afterward, each of the readers modified their face by adding clay-like protrusions. The interplay of confessional and transformative energies was very much located in the notion of hairstyling. The tradition of reformulating one’s identity through the visible transformation of self as especially evident in hair was entirely laid open by the participants in this performance.

Nancy Buchanan, Kim as Roman Lady, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles.

In the most recent work, Hairbrain (2020) there is a cast acrylic element that looks like the upper half of the brain. It rests on an acrylic stand that raises it a few inches off of a mirror in which a locket of hair embedded within it is visible. Harkening back to Victorian mourning jewelry and the notion that a wisp of hair contains a romantic power and evocative qualities, the pristine transparency of the cast acrylic creates a strong counterpoint to that sentimental introjection by way of the whorls of the cerebral cortex. In this dialogue between sentimentality and logic, between something that might be almost abject and yet is most certainly beautiful, Buchanan is interested in drawing the viewer in without providing them with a single judgmental solution.

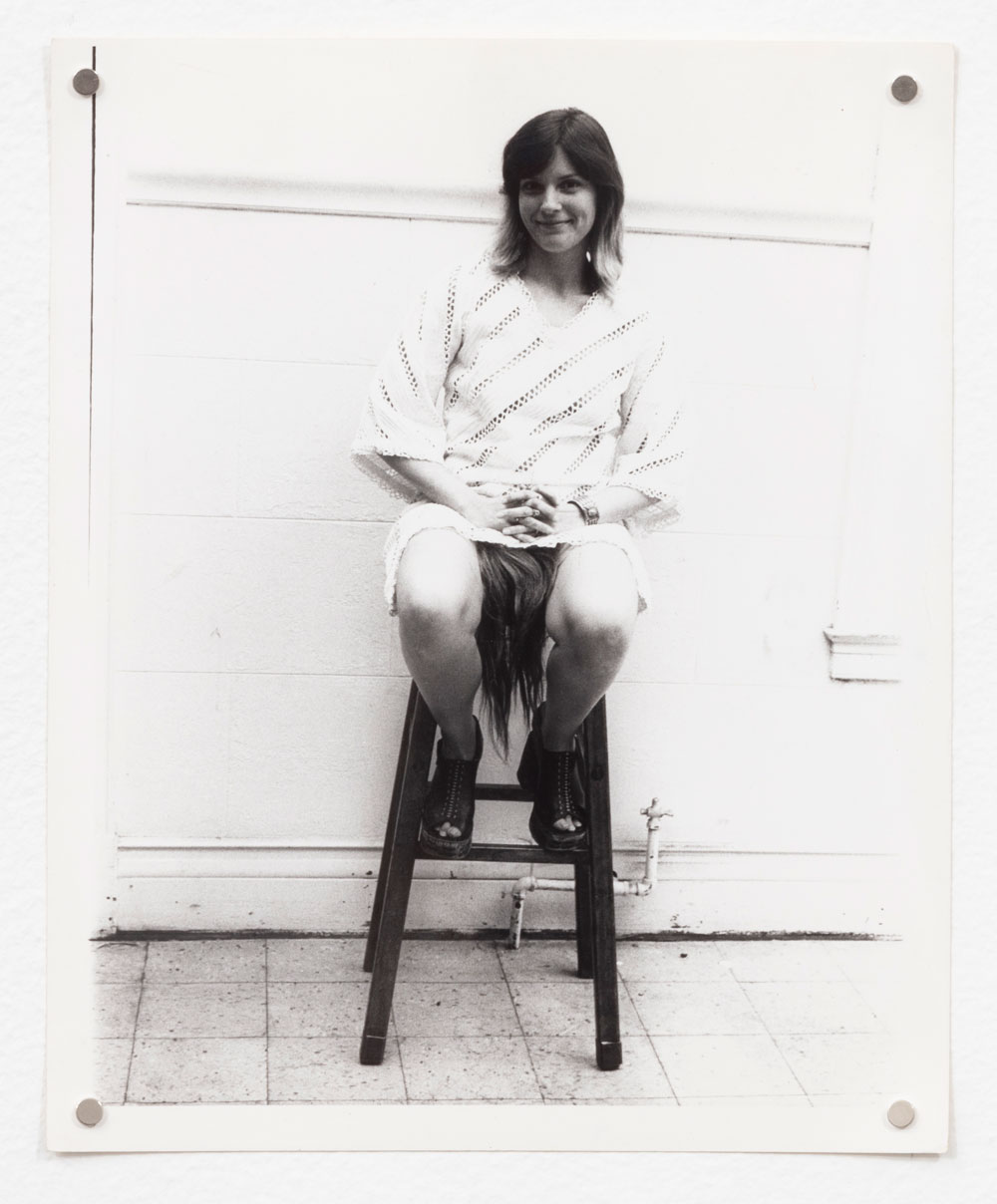

Much of the playful yet provocative conundrum that Buchanan sets up time and again for the viewer to consider is exemplified by Hair Art, Dirty Art, (1974), a photograph in which the artist is seated on a stool, facing the camera after having carefully placed a wig between her slightly open thighs. The bright smiling face moves the interpretation in one direction, while the flowing hair bursting out below the dress moves it in an entirely different arc. It is this contradictory tension that runs throughout “Crowning Glories.”