There are two fantastic shows up right now at Marc Selwyn Fine Art in Beverly Hills—both devoted to artists who have some claim to the term, legend—not as an honorific exactly, but simply in terms of the way they have lived their lives—bringing the full scope of their imaginations to bear on every moment. Cameron (born Marjorie Elizabeth Cameron, 1922-1995) had a life that took her from the Plains states to both coasts and the frontiers of science, technology (and military intelligence during World War II), and (more or less at the same time) art and the occult by way of JPL rocket engineer and tech visionary, Jack Parsons. Parsons drew her into his extended circle of scientists and engineers, occult and ‘dark art’ practitioners like Aleister Crowley, and actual artists including Wallace Berman and (fellow Crowley enthusiast) Kenneth Anger. Parsons’ untimely death likely drew her further into both art and the occult (drugs—e.g., peyote—probably didn’t hurt either). After some time migrating between California and Mexico, she settled for a time in the Los Angeles area where it might be said she made art as a fully integrated part of her practice in magic, the occult, and astrology. Her glamour and penchant for the phantasmagorical were a magnet for Anger and Berman both, and Anger featured her prominently in his film, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. Curtis Harrington featured her in two of his films, including Night Tide (which also features a very young Dennis Hopper, equally enveloped in the film’s mystery and romance—possibly his most important film role up to that time).

Cameron probably destroyed as much of her art as what she left behind—and it’s remarkable we have enough left for the solo exhibitions of her work that have appeared since approximately 2013-14, which is when former MoCA senior curator Alma Ruiz and Yael Lipschutz curated Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman for MoCA’s Pacific Design Center galleries). Marc Selwyn first exhibited Cameron’s work in the Fall of 2014 (Cinderella of the Wastelands, a show essentially re-mounted in 2015 at Deitch Projects in New York). Most of the credit for this probably goes to the preservation work of the Cameron Parsons Foundation, and more specifically its director, Scott Hobbs, who curated the current show (The Lion Path: Art, Astrology, and Magic) at the gallery—and the magic and astrology are very much on view. (The show includes six of the customized individual astrological charts she plotted for friends, clients and famous acquaintances—including John Barrymore.)

Which is a long way of leading up to the magic I really want to talk about here—a kind of magic that almost literally ‘caught me in its spell’—conjured by the second legend on view, Vaginal Davis.

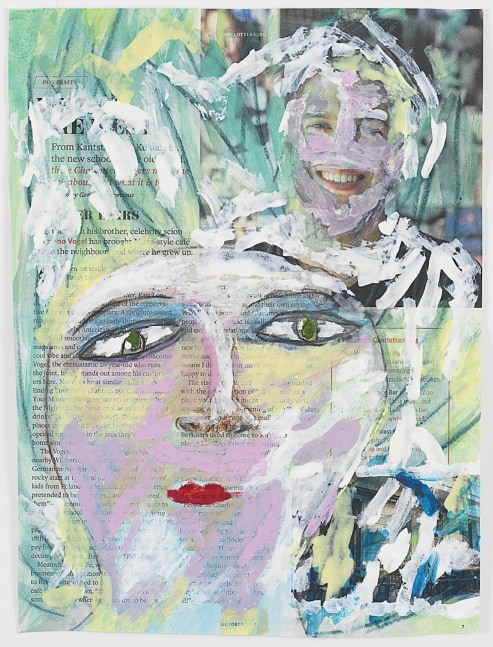

Vaginal Davis, “At the End of A Perfect Day” (2018), Watercolor pencil & various cosmetic pigments, witch hazel, perfume, hairspray, analgesic (Anacin, Excedrin), etc. on paper (magazine page)

Vaginal calls them ‘make-up paintings’—and I’m not sure it’s simply because she uses quantities of cosmetic pigments as their primary chromatic components. I first encountered these kinds of paintings in her contributions to Witch Hunt, the 2021-22 exhibition curated by Connie Butler and Anne Ellegood (an exhibition that really began to take shape as early as 2017, instigated in part by political developments of that year) for the Hammer Museum and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. (Some of the works in this exhibition were made around the same time as the works in Witch Hunt.)

At the time I first viewed those paintings (at the ICA-LA), they seemed to have an aspect of automatic writing or drawing, a kind of post-Arp, post-Fluxus surreal and psychological quality that, within the frame of that exhibition, dovetailed brilliantly with more explicitly cultural-political aspects articulated by artists such as Bouchra Khalili and Candice Breitz. Less than two years later, though, they seem far from unconscious or ‘automatic’, but deliberated, meditative—composed not in any conventional sense, but as if conjuring (more than simply recalling) a face, persona, visage—by tactile as much as visual memory—an alchemy of colors, balms, contouring and tracery; an anointing and incantation. (I’m thinking now of the Joanne Woodward times seven painting from that show—the schematic oval of her face … drawn seven times—seven egg-like Joans in our nest….which seemed to carry an association with her performance in The Three Faces of Eve. How many Joanne’s can be made over into the memory, the icon of each performance, that will be carried with us to the grave?)

They’re pictographic dream faces and Vaginal is tracing her dreams (and ours), and memories channeled and recomposed in dreams into these icons of possession, obsession, abandon, and disillusioned romance. Or simply what is lost, left behind, or slipping from our reach—or time itself. It’s not about ‘identity’ exactly, but it has something to do with who we are, where we’ve been, and what we have left to show for it. I imagine Vaginal composing these paintings at her dressing table—a newspaper section or magazine, the odd letter, bill or postcard stashed somewhere alongside the bottles of toner, face cream jars, concealer, brushes and accumulated boxes, bottles, palettes and compacts of powder and makeup. Presumably there are a few cups or glasses, too—of coffee, water, and maybe something from the night before. Which is why there are also bottles of analgesics alongside the routine and not-so-routine prescriptions. Hassle enough to deal with hair and makeup after a good night. Now, the nights are never long enough and it always seems to be too early in the morning, even as the morning stretches toward noon.

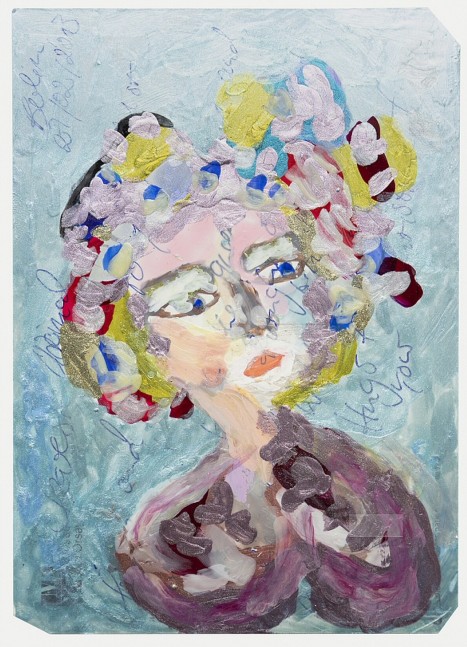

Vaginal Davis, “The Test of Christy Himmelfart, April Fool’s Day” (2019), nail varnish, rouge, mascara, … Aqua Net extra super hold, etc., on cardboard postcard

We spend so much time constructing this façade, this mask—no less armored and fortified than any other part of our person. Somewhere beneath the reflected ruin we can trace the not-quite-original architecture—altered by actions and engagements, time and events, and conceivably a more willful intervention or two. I can easily see the artist looking down from the reflection in the mirror and taking up last night’s invitation card, someone’s postcard, a pestering letter or piece of publicity and inverting it with a tracing of the eye pencil she was just moments earlier moving across her eyelid, or willfully reshaping its tone with the contouring brush that just touched those cliffsides we once called cheeks. (Is there anger here? A little, maybe. Regrets—we’ve had a few. But then we’re forever shadowed by these ‘jeunes filles en fleur’….) Here’s a beautiful face—wrinkles dissolving beneath aspirin tamped down beneath glittery gloss….

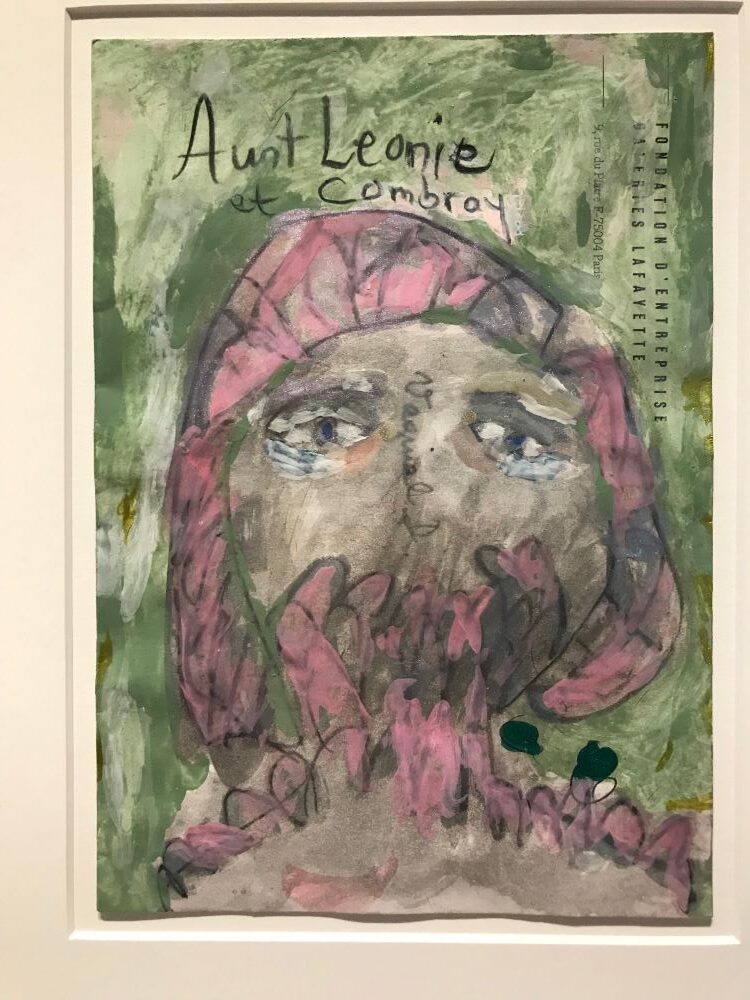

Vaginal Davis, “Aunt Leonie et Combray” (2019), mixed media on paper

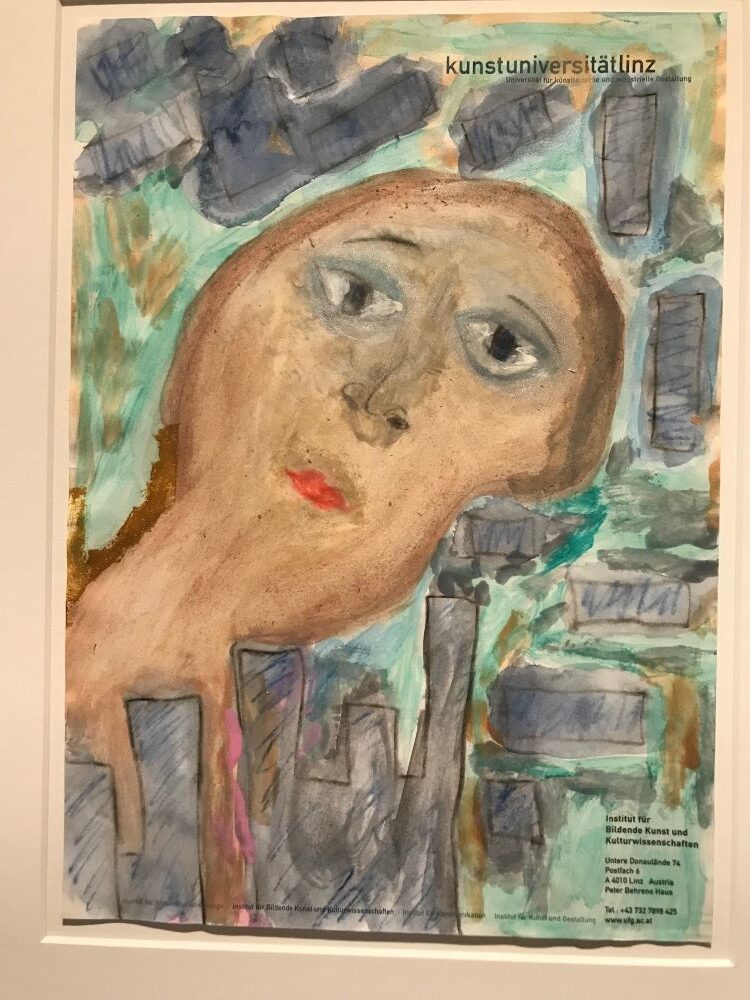

It’s a dream world we know in life, in dreams, and certainly books and movies. I just about melted down between Aunt Léonie et Combray (2019)—with its evocation of pink hawthorn blossoms (Vaginal’s signature a grin-grimace median between ‘Swann’s way’ and that of the Guermantes) enveloping the face in a kind of cloche-bonnet, and Shopworn Angel, ineluctably associated with that impossible-to-capture face of Margaret Sullavan. I’m not sure if anyone—even Lubitsch—really captured Sullavan’s protean persona; and between struggles with hearing deficits and depression, Sullavan’s life and career was itself a struggle for self-possession. But there’s something of her eyes and mien in Vaginal’s cloud-like version—that sense of fatalistic disillusionment in her eyes set against her stoically sealed mouth—looming over rectangular crenellations (referencing her own embattled state or her co-star’s (Jimmy Stewart) fictional one—who could say?).

Vaginal Davis, “Shopworn Angel” (2017) watercolor pencil, nail varnish, lip stain, eye shadow, perfume, hairspray, analgesics, etc. on paper

It’s interesting that ‘Tante’ Léonie becomes ‘Aunt’ here—Vaginal personalizing the relationship, effectively assuming the role of the dreaming, remembering, ‘Marcel’—perhaps recalling real ‘aunties’ who saved her (and so many of us) and the safe places parents can’t object to, negotiating the social (and political) minefields on the other sides of those blossomed embankments. I’m not sure if recent generations look at old movies (whether in cinemas or streaming media) the way mine did. But Shopworn Angel strikes a number of resonant notes in the way both Sullavan’s and Stewart’s characters seem to unfurl—Sullavan’s fiercely self-confident Broadway star, Daisy, whose wealthy beau can’t persuade her to commit; Stewart’s hayseed Bill, literally bowled over, bragging to stand up to the bullies of his army unit—and put to the test when his platoon buddies ask him to introduce them to the star. This, too, in an odd way is about safe spaces, or making (very) scary spaces safe—if only for a narrow window of time. It’s what I’d call a mirror question: who do we have to pretend to be today, tomorrow? who do we have to be right now? who do we want to be? And finally, who are we really? And there’s no satisfactory answer to that last one.

There’s one last note (literally)—of the sort that maybe actually falls on the dressing table. In the movie, it’s delivered to Daisy’s beau, Sam, while Daisy is on stage and about to launch into her show’s big musical number. It’s from (what was at that time called) the War Department and even if you haven’t seen the film, you can guess what it is. But the show must go on even as the world around and between them is exploding. (Presumably the Anacin ‘fast pain relief’ and Excedrin migraine tablets help.)

I realize now that what initially struck me as a kind of ‘automatic’ drawing is really something closer to autofiction. Moving from one painting to the next, there’s a certain randomness that (deliberately) confuses and complicates what is neither anecdotal or incidental narrative nor iconography. Her Cardboard Lover (2017) (a 1942 M-G-M movie directed by George Cukor, featuring Norma Shearer and George Sanders, which for some reason I’ve never seen) appears to materialize out of a few flower petals strewn at the bottom of a piece of blank UCLA letterhead (specifically from the Department of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Studies—who knew?). I’m guessing Vaginal was a guest lecturer and began conjuring the thesis or subject of her lecture from a temporary office in Rolfe Hall. It must have been worthy of Roland Barthes. How else do you get from that to the rose, mauve and amethyst feathers and ribbons that conjure up Juliet Prowse (2018)? We can assume M-G-M had something to do with it, but I’m not sure how many contemporary viewers will remember who exactly Prowse was. She was a regular on television variety shows of the 1960s, but it was her dancing—and specifically her dancing for the 1960 film, Can-Can, that first brought her to prominence in America. (Vaginal and I appear to have endured similarly chronic exposure to 1960s network television and the Late Late Show, but she appears to have seen a lot more dance than I ever did at that age.) Vaginal drops her pigmented feathers on what appears to be a piece of publicity, and it’s notable that Prowse’s career exploded in a similar way—from actually dancing the can-can in French and Spanish nightclubs to her role in the 20th Century Fox film; and from that point on, Prowse seemed to be forever bursting from feathers on American screens and stages until accidents and illness took her from us prematurely.

Vaginal Davis, “Cyd Charisse” (2018), watercolor pencil, cosmetic foundation, eye shadow, rouge, nail enamel, witch hazel, peroxide, hairspray, Henbane, etc. on found paper

Vaginal Davis, “Raven Wilkinson” (2018), watercolor pencil, cosmetic pigments, nail enamel lacquer, peroxide, witch hazel, hairspray, Mandrake & Henbane, etc., on found paper (magazine page)

Some of these paintings are really masterpieces of expressionist collage. (E.g., Illegitimate Daughter of a Texas Congressman (2018) (which for all I know could have been pulled from a newspaper headline—would we expect anything less?); or At the End of a Perfect Day (2018) (which believe it or not also comes from a film, and which, unlike the aforementioned Shearer vehicle, I have seen—and there’s a personal connection for me there, too).) But you can’t help noticing how many dance icons make it into these late night (or early morning) make-up table meditations. I can’t say Vaginal’s Moira Shearer (2018) looks anything like Vicky Page, the ballet star heroine of the 1948 Powell/Pressburger film, The Red Shoes—likely to burn a hole into the brain of any child under 12 who has an opportunity to see it; this image looks a bit more Firebird (which I have no doubt Shearer also danced at one point or another). But then she also played Titania in a stage production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and, much later, Vivian in Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960). Martha Graham and her sister Geordie (who played a very important role in managing the Graham Company) are here. Also Raven Wilkinson, prodigy-progeny of the Harlem Renaissance, who struggled to break the color barrier in the classical dance world before emerging a great international star. Cyd Charisse is here, too—though something of Cookie Mueller’s soul speaks to me through this smouldering gaze.

I suspect Vaginal has quite a few more stashed away in her Berlin studio. There are any number of icons who by now have probably entered her pantheon—Josephine Baker, Gwen Verdon, and later (around the time I suspect Vaginal began seeing ballets), Margot Fonteyn (Shearer’s colleague at Sadler’s Wells), Nureyev, Baryshnikov (men, yes—but androgynous icons on the ballet stage), Suzanne Farrell, Peter Martins—we could go on.

But while the Grahams and the entire Denishawn legacy forever burns its notion of the iconographic into us, it’s The Red Shoes that really marks us for life. Personally, I think the Technicolor film process/spectrum has something to do with this. It’s about dance, sure; and the consuming love of music, dance, art, theatre, and vision. But it’s also about when these things become passions that overtake and control our lives, rule our destinies. It’s about seduction and—as the Massine ballet lays out in the film—the idea of possession, the notion that something outside oneself can take hold of us until death alone loosens its grip. It’s about art as an incomparable and fatal pursuit—and the bargain we strike with our demons to pursue it.

It’s significant that Shearer’s character, Victoria, makes the first move in the film—standing at a bar at a party ordering the same drink as her soon-to-be dance master and company boss, Boris Lermontov (a masterful Anton Walbrook). “Why do you want to dance?” he asks her. She responds with an absurd yet calculated question. “Why do you want to live?” “I don’t know, but … I must,” Lermontov replies, both pensive and provoked by his soon-to-be star.

I can only imagine Vaginal asking herself the same question—somewhere around the age of 12. And now and forever, interrogating the demons in the mirror while she toys with pencils and pigments on the dressing table. It’s that last part of the Symposium Plato never quite got to, but Kierkegaard probably figured out. It’s that dance we do before the lights go out.

Vaginal Davis — Macha Family Romance runs through May 27, 2023 at Marc Selwyn Fine Art, 9953 Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills, CA 90212.