“Jesus, you know, it wasn’t supposed to happen like this. Even if it strikes me now as having been inevitable….”

“I want to know what it will be like once all this (all this: the inexorable, the inexpressible) has become distant memory. I’ve always hated the way the most powerful experiences so often end up resembling dreams, I am talking about that taint of the surreal that besmears so much of our vision of the past. Why should so much that has happened feel as though it had not truly happened? Life is but a dream. Think: Could there be a crueler notion?”

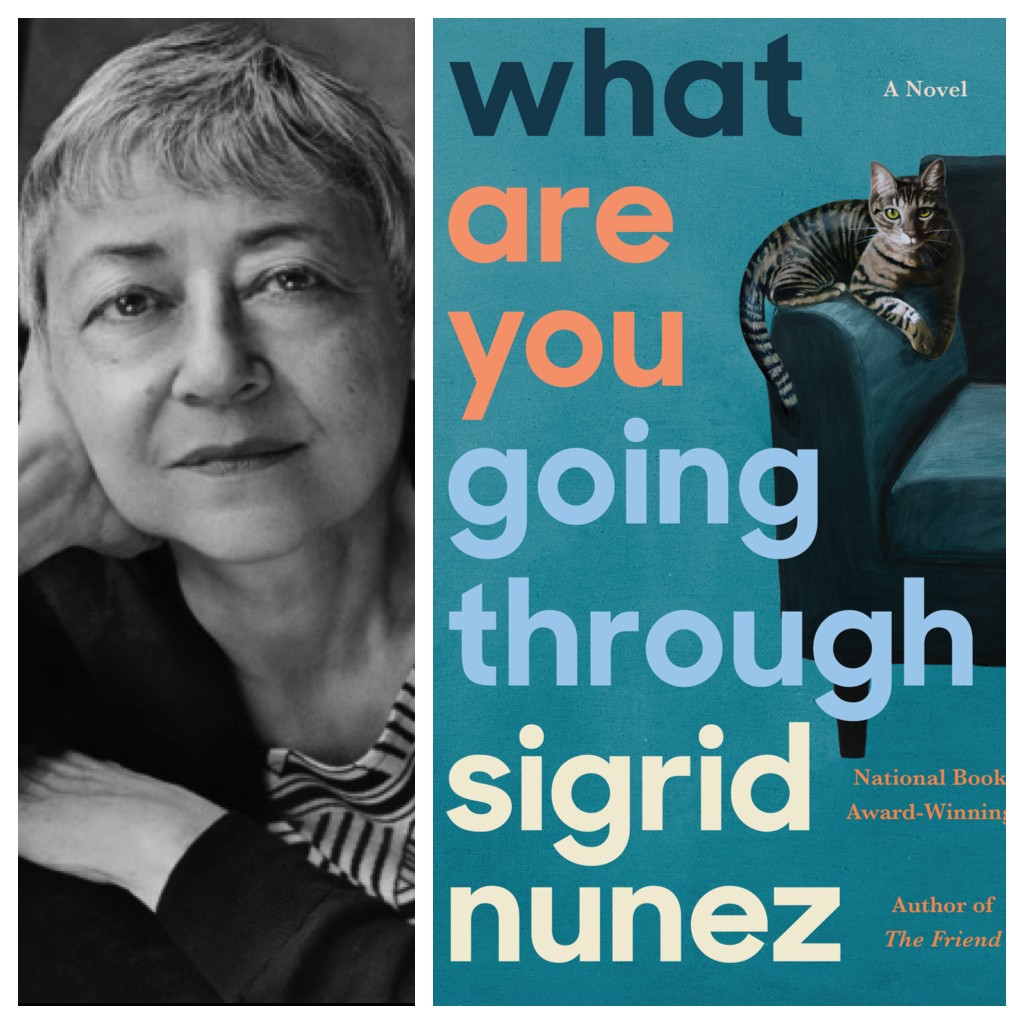

Sigrid Nunez, What Are You Going Through (Riverhead)

These words from one of my favorite things from this year in which we felt death press upon us as ephemerally as a gust of wind, as ponderously as the mechanical wheeze of a ventilator, deadly as live fire, even as we insisted that life mattered—in particular those lives which our law enforcement agencies valued least of all. Why should one murder be the breaking point? It must be said that George Floyd’s murder was preceded by what seemed like an unprecedented string of outrageous police homicides. That so many saw it as it unfolded no doubt was a contributing factor; but after a four-year subversive shit show of constitutional democracy under assault, of undisguised brutality, racism, and xenophobia, of unrelenting cruelty and callousness under color of law and the trappings of state, we were all face-to-face with a mushroom cloud chain reaction whether on the street or behind plate glass.

One thing I think can be safely said about 2020: although it actually did feel very dream-like and surreal intermittently as the days unfurled and events unfolded, as we continue through its last act bleeding into 2021, its long-term consequences will not be experienced anywhere remotely as dreamily or surreally. If we are not already experiencing the scarifying cruelty of its devastation to our health and well-being, our personal and household economies, the altered conditions we face due to climate change, and the material changes to our lives imposed by economic and environmental shifts well beyond 2021, we may feel as much or even more of a restraint on our accustomed activities, movements, habits and behaviours, as the present lockdown and the last. To the extent we are required to change our lives, we must expect that such changes may not necessarily correlate with what we regard as the “pursuit of happiness.”

And in essence this is the first of my ‘favorite things’ of 2020, and the keynote: the end of what we once might have called ‘normalcy’. Part of this is simply a matter of shifting perceptions. The Trump regime (with an assist from other autocratic, authoritarian or totalitarian, fascist or other right- or sectarian-leaning regimes, as well as the global coronavirus pandemic), not simply through an unrelenting assault on the social, political, and ethical ‘norms’ of executive procedures and prerogatives within a constitutional government, but its assault on the integrity of the institution and institutional identity itself, certainly accelerated this. But it was hard to ignore the extent to which mainstream media played along. Jordan Peele could write a movie about it (and probably has).

How is it that we normalize what we know to be wrong? And I mean we—because we all do it to some extent simply by the way we address or reference the status quo, the things which have always figured in large or small ways in our lives—the way we live and work, the ways in which we’re schooled and educated, aspects of the technology that supports these functions, aspects of our government, legal and judicial systems.

I think the playwright and screenwriter, John Patrick Shanley may have summed it up best in his script for the 1987 Norman Jewison (M-G-M/Star Partners II) film, Moonstruck: “Snap out of it!” Sometimes that’s what it takes: a snap, a slap, a traumatic break—and one of considerable force. It is more than an intellectual or conceptual leap to arrive at, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…,” to say nothing of its potential implications.

Return of the Birds

Return of the Birds

I’m not sure at what point I began to notice an increase in the number of birds, but it wasn’t that long after the initial shut-down. Timing had something to do with it: the first lock-down/shelter-in-place orders in Los Angeles and the rest of California more or less coincided with the beginning of Spring. No more than two weeks later, the difference was sharply noticeable – just as the decline of birds — their numbers and activities — has been at least as noticeable over the last decade or two. I can only speculate, but I have to wonder if this has something to do with increasing observations (and appreciations) of birds in many different quarters over the last nine months from coast to coast.

It’s not as if I suddenly took up the amateur study of ornithology in my pandemic lock-down time or organized bird-watching in my neighborhood or Griffith Park. But it was as if birds had dialed up the volume on their morning, early afternoon, and evening chirping and singing. To hear that music again and realize what it meant was an ecstatic moment. Some of my favorite music is inspired by nature, natural sounds, birds. Beethoven is clearly inspired by birdsong in his 6th F major (“Pastoral) Symphony. Messiaen was obsessed with birds and makes a special study of birdsong with his Catalogue d’oiseaux.

Postscript: We’re not out of the woods (apologies for that chestnut) on this decline yet: e.g., the bird sanctuary in Griffith Park is still woefully under populated (though also simply under-populated with bird habitats — i.e., trees); there were reports of massive bird die-offs over Arizona and New Mexico this past summer—birds just dropping from the over-heated skies; etc. We have a long way to go.

Black Lives Matter / Trans Black Lives Matter / All Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter / Trans Black Lives Matter / All Black Lives Matter

Between Breonna Taylor, Eliljah Cummings, and the on-camera murder of George Floyd (really a species of lynching), as with so many Americans, something in me broke, and has yet to mend. Although I could not go out for more than one demonstration, terrified as much by transmission of the coronavirus as by the L.A.P.D., I poured my pathetic earnings into at least half a dozen organizations and would have happily given more, had my attention not turned (after Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders failed to secure the nomination) to the priorities of unseating the first fascist psychopath to occupy the Presidency (to be honest about this, the entire duration of the Trump administration felt like a foreign occupation), securing and building on the Democratic House majority, and turning as many Senate seats blue as possible. Racism (like authoritarianism, totalitarianism) will always be with us on one level or another, but #BLM, like the battle to save the planetary biosphere, is one of the campaigns we carry forward until our last breath.

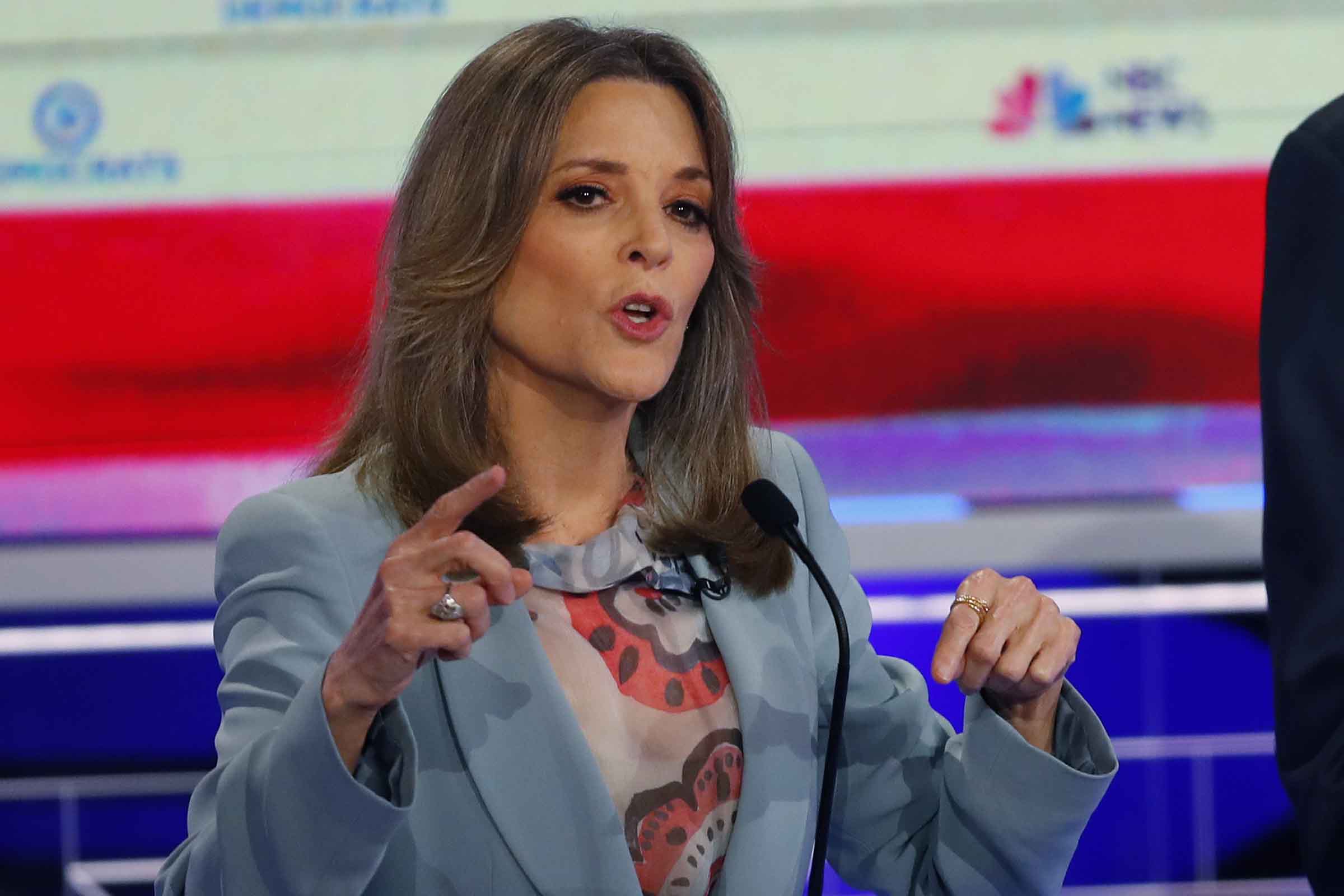

Democratic presidential candidate author Marianne Williamson speaks during the Democratic primary debate hosted by NBC News at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, Thursday, June 27, 2019, in Miami. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

The presidential candidacy of Marianne Williamson

Don’t get me wrong: I went with Elizabeth Warren, with Julian Castro a close second and Bernie Sanders a distant third. (Politics is hard ball; and—forget about bats—the other team and their fans have their knives out for you.) But I fell in love with the notion, the sheer guts it took to bring a foundationally alternative agenda to the 2020 field, to those kangaroo-court-beauty-pageant-game-show-cum-debate stages. You think socialism is radical??? Forget about the ‘God’ stuff — this is about love — as in “what we were born with”; as opposed to the fear that “we learned here.” Too bad hate is always such an easy sell, as 73 million-plus Trump voters will happily confirm. Easy to distrust love when half of those presuming to offer it are not really offering love at all. Also easy to see why love might be conflated with religious faith — love is always a leap of faith. Setting to one side Williamson’s ‘God’ construct, her agenda is really on a continuum with most consciousness-expansion movements since the Enlightenment — building a kind of radical empathy as if through a cognitive behavioral approach, opening and expanding the imagination. If there’s a hiccup in her ‘program’ to speak, it’s probably the notion of ‘practicing forgiveness’— a little dangerous where humankind has already pushed way beyond the tipping point, inflicting so much unforgiveable damage to the planet (and, needless to say, each other). Still, as we were fighting off the haters with bricks, bats, choice nouns and adjectives, and a whole lot of dollars, it was something we needed to hear.

Re-reading Rachel Carson

Re-reading Rachel Carson

Speaking of birds, long before we had a clue the pandemic was going to be moving anywhere beyond Wuhan’s borders, I had chanced upon an early title of Rachel Carson’s, originally published well before The Sea Around Us or her landmark call to environmental action, Silent Spring, Under the Sea-Wind, and began tearing through it, as I might through a great poem or piece of inspired fiction. Describing the life-cycles, processes and functions of aquatic and avian life — and inter-connectedness of it all, she isolates individual specimens and creates fictional trajectories for them, propelling us alongside as if we were part of the same flock, swarm, school. (We are, of course.) I had wanted to look at Silent Spring again after reading Andrea Wulf’s fantastic biography of Alexander von Humboldt, The Invention of Nature in 2018 or 2019, and now began going through all of Carson’s books again, rediscovering the breathtaking poetry she observed in nature (and the literary poetry she referenced and drew comparison to in, for example, The Sea Around Us), and the poetry of her own writing, her voice and sensibility.

Sigrid Nunez: What Are You Going Through

Sigrid Nunez: What Are You Going Through

Poised between radical empathy (specifically, empathy in extremis, as articulated by Simone Weil, who inspired the novel’s title) and a clear-eyed reading of the variety of human experience of the world, including its worst corruptions and pathologies and what they have made of it, What Are You Going Through feels at moments as if Nunez picked up right where she left off in her celebrated last novel, The Friend. Again death is cheated, only to return—not with a vengeance, but absurd and inexorable, in full view of our ravaged legacies, the catastrophes looming just beyond the horizon. We don’t necessarily need the “reality of sickness,” the truths “born of affliction” (I’m quoting Sontag here) because we’re immersed in it. Nunez’s book is a puzzle of paradox and contradiction, unblemished by false consolation, but not without moments of quotidian transcendence.

Aside from a few stand-out novels like this one, I can’t say I actually read all that much during 2020—preoccupied with politics and activism, a seemingly continuous stream of assaults and outrages on bodies planetary and politic, an often demanding job, and the minutiae of daily life under a global pandemic. In addition to Carson, I re-read a bit of Sartre and Genet; also Leonora Carrington. The few other highlights included Jenny Offill’s Weather, read alongside the late poet, Holly Prado’s chronicle-poem, Weather; Reginald Dwayne Betts’ searing collection of poems (not a few of them composed in extremis), Felon; Bill McKibben’s Falter, Wayne Koestenbaum’s Figure It Out, Eugenia Cheng’s x + y; Fayette Hauser’s The Cockettes: Acid Drag and Sexual Anarchy; Jim Carrey’s (with Dana Vachon) Memoirs and Misinformation, Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court.

Rediscovering Television / Michaela Coel: I May Destroy You

Rediscovering Television / Michaela Coel: I May Destroy You

Viewed against the context of my life, it’s amazing how little television I watch generally, and even more amazing how little I’ve watched over the last few years, which many view as a kind of zenith of the medium. Having caught bits and pieces of this series or that through various launch screenings over the past several years, it wasn’t as if I was entirely clueless as to what might be in store, but as I dove a bit deeper, my eyes and ears opened again to different ways of telling the story or putting across a set of ideas, feelings, actualities, moment by moment. Here’s the thing: during these zenith years—really the past decade—television has been transformed (partially through the influences of streaming services, YouTube, and the gamut of digital media). Far from the packaged, 3-camera thing it was once, it’s an entirely different grammar and syntax. You could almost reduce the whole of it down to camera(s) and editing – cameras and cuts, jump-cut of jump-cuts: here’s where you were, here’s where you are—and suddenly we comprehend an entire stretch of ground.

I can still become a bit impatient with it. It’s generally slower than print and I am occasionally tempted to fast-forward through certain streamed series (though there are instances when the opposite is true). I had to jump forward and back to really sink my chops into the stew of content. And then I came to Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You; and, well you know how it is when you encounter that thing that swallows all media; that is words and music and stage and screen and street and theatre and contemporary life and a swath of eternity — okay we’ll set aside ‘eternity’ for the moment. But Coel has created something that both snaps our heads around in several directions almost simultaneously while meeting us (okay I’m about to exaggerate again) right where we live. Alright where some of us (or our friends?) live. Or where we lived about 10 years ago. Except that we didn’t learn as much as Coel has about that place — that multi-compartmented consciousness, those tangents, those boundaries — that keep flexing, moving (did someone just move the goalpost? am I being too sensitive??). Personhood, respect, joy, integrity, freedom, love.

Other favorite television encounters of 2020: Phoebe Waller-Bridge/Fleabag, Olivia Colman (in The Crown), Trevor Noah/The Daily Show, The Queen’s Gambit.

Gunda (Victor Kossakovsky, dir; written with Ainara Vera; Neon/Hallstone/Larsen/Phoenix)

Gunda (Victor Kossakovsky, dir; written with Ainara Vera; Neon/Hallstone/Larsen/Phoenix)

It almost goes without saying that I saw very few films in 2020 (I’m one of those die-hards who prefers seeing movies on the big screen); but given that Netflix was already there, it was inevitable we would have opportunities to take in what would normally have been theatrical releases. Gunda might well continue as one of my favorite things of 2021—it streamed for viewers through New York’s Film Forum the first part of December, but will not officially open or be available for commercial distribution until March of this year. Although many of us have certainly imagined seeing the world in this fashion (and conceivably have — say, on a playing field), we’ve never seen it on film, and through an entirely different mindset — which is to say, another species’ perceptual, cognitive and behavioral apparatus — in this instance, that of a prodigiously large sow, who has very recently given birth to a litter of piglets. Gunda takes us to a specific place on the planet, and another way of encountering, experiencing, reacting to an environment and set of relationships that’s largely non-human (though humans, along with their ghastly machines, do intrude intermittently) — much closer to the ground, the skin of the earth itself (and the underside of that skin). As with the earth itself (or for that matter the farm that is Gunda’s habitat), there are physical, sensory (and yes, intellectual) limitations. But what does it mean for the human viewer that pigs also experience the wonder and delight of sensory experience of the physical environment — the sun, rain, earth? That — without anthropomorphizing — they clearly have thoughts, emotions, individual characteristics, (dare I say it?) personalities. Without spoiling the experience, the film’s ending is not everything one might like it to be. But you will not easily put Gunda or her children out of your mind regardless of what you choose to put on your plate.

Aside from this film that practically pushes all others out of my sightlines, I enjoyed Radha Blank’s The Forty Year-Old Version (Netflix); and Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Netflix/Likely Story) was pretty irresistible — but don’t jump to any conclusions.

Although most of us are too well acquainted with Twitter (and after four years of non-stop tweets from a very public criminal psychopath may be on the verge of complete exhaustion from it, Facebook and any number of social media platforms), there is nothing quite like Instagram—especially for artists who, however secretive about their projects, studio practices, or techniques, almost always have something to show us. Here are just a few that kept me going through 2020.

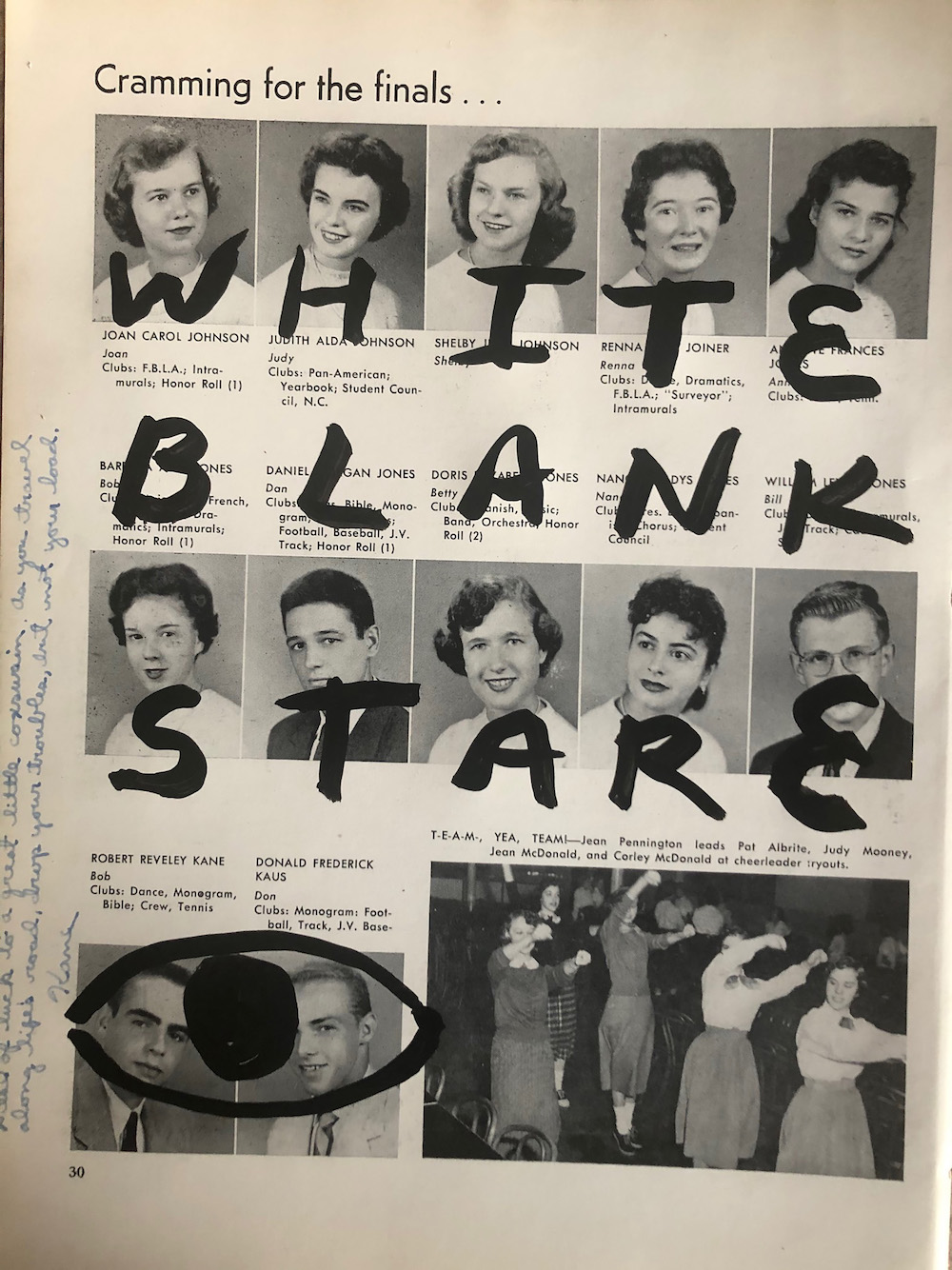

“White Blank Stare,” 2020

Karen Finley: Anyone who read the excerpts from my conversation with Karen Finley in the last issue knows that ‘White Blank Stare’ stopped me dead in my already catatonic early morning tracks, but that’s what these streamed images at their best have the capacity to do. We don’t need to be primed; context be damned—all it has to do is move us in the moment and trigger those multiple interior dialogues that ultimately propel us to action.

Carolyn Marks Blackwood, October 10, 2020, “The world is still beautiful.”

Carolyn Marks Blackwood: The sheer beauty of Carolyn Marks Blackwood’s landscapes is utterly transfixing, but implicit in that transfiguration is a kernel of dread that such idylls might be threatened or—goddess forbid!—polluted, damaged or in any way irreparably altered. In other words, another kind of ‘wake-up call’ inspiring simultaneously hope and urgency.

Brendan Lott: Since some point during the first pandemic lock-down, Brendan Lott has been posting images from his Safer At Home series. The subjects are mostly his neighbors across the street, whose loft windows are shot at just the right angle to preserve anonymity while disclosing sufficient detail of lives lived, interests pursued or in suspense, the masquerades that continue behind closed doors. Lott is certainly not the first or only artist or photographer to peer into the windows (rear, side, or façade) of his neighbors. But he captures something crystalline about this moment—not simply about the nature of solitude or sequestration or the way we live now, but the way we frame our lives, the ways in which we encounter and (conceivably) know ourselves. Yes, there is loneliness, frustration, even desperation — but it’s as much our own as its subjects’. With apologies to the late, great John Prine (one of Covid-19’s first victims), say “hello in there.”

Brendan Lott: Since some point during the first pandemic lock-down, Brendan Lott has been posting images from his Safer At Home series. The subjects are mostly his neighbors across the street, whose loft windows are shot at just the right angle to preserve anonymity while disclosing sufficient detail of lives lived, interests pursued or in suspense, the masquerades that continue behind closed doors. Lott is certainly not the first or only artist or photographer to peer into the windows (rear, side, or façade) of his neighbors. But he captures something crystalline about this moment—not simply about the nature of solitude or sequestration or the way we live now, but the way we frame our lives, the ways in which we encounter and (conceivably) know ourselves. Yes, there is loneliness, frustration, even desperation — but it’s as much our own as its subjects’. With apologies to the late, great John Prine (one of Covid-19’s first victims), say “hello in there.”

Jeremy O. Harris: The chameleon intellect, genius playwright of Slave Play, fashion-plate, insouciant raconteur and de facto on-line magazine-maker viral enough to stare down the corona-virus. Simply one of the funniest and most brilliant feeds on the platform—which is sort of what we expect and certainly what we need. His Coronavirus Mixtapes are pitched somewhere between a Tod Browning or John Waters freak-fest and a Paris Review for the TikTok generation.

Jeremy O. Harris: The chameleon intellect, genius playwright of Slave Play, fashion-plate, insouciant raconteur and de facto on-line magazine-maker viral enough to stare down the corona-virus. Simply one of the funniest and most brilliant feeds on the platform—which is sort of what we expect and certainly what we need. His Coronavirus Mixtapes are pitched somewhere between a Tod Browning or John Waters freak-fest and a Paris Review for the TikTok generation.

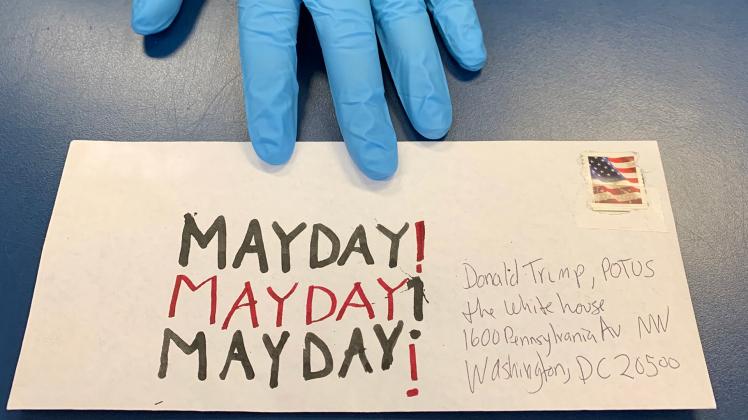

Susan Silton: A potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past; MAYDAY! MAYDAY! MAYDAY!; Quartet for the End of Time

Susan Silton: A potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past; MAYDAY! MAYDAY! MAYDAY!; Quartet for the End of Time

To look at Susan Silton’s projects over the last four years (or conceivably, the last 20), you might think she anticipated all or some part of the disasters that have unfolded over the last four years since a certain psychopathic racist-fascist corrupt/failed real estate mogul television personality was installed as the head of the executive branch of the American government and commander-in-chief of its armed forces. Silton began releasing the sequence of 1930s New York Times front pages that comprise A potentiality… in 2018, but had been showing them again on Instagram as the House prepared its articles of impeachment against the currently sitting president. That the failed impeachment might be followed by a global pandemic could hardly have been anticipated (except, notably, by a number of scientists, artists and writers); but Silton was prepared to address the actuality in real time, initiating a mail project intended to go ‘viral’. The result was her participatory mass-mailing of ‘in-memoriam’ letters consisting simply of the name of an individual who had died from the virus mailed to the sitting president with the emergency signal MAYDAY! MAYDAY! MAYDAY! emblazoned on the envelope.

Even prior to these projects, though, her re-imagined and re-conceived staging of the Olivier Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time had sounded a quiet but brightly piercing alarm for the darkness to come. In her staging (which included that non-pareil pianist of contemporary music, Vicki Ray), one of the performers steps forward to recite in staggered fashion a line quoted from Hannah Arendt’s Men In Dark Times: “Even…Even in…Even in the…Even in the darkest….” (The actual sentence reads: “Even in the darkest of times, we have the right to expect some illumination.”) In her book, Arendt goes on to say that “such illumination may come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time-span that was given them on earth.” That flickering light is all we ever really have and Silton manages to connect it like a beacon to the community around her.

Even prior to these projects, though, her re-imagined and re-conceived staging of the Olivier Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time had sounded a quiet but brightly piercing alarm for the darkness to come. In her staging (which included that non-pareil pianist of contemporary music, Vicki Ray), one of the performers steps forward to recite in staggered fashion a line quoted from Hannah Arendt’s Men In Dark Times: “Even…Even in…Even in the…Even in the darkest….” (The actual sentence reads: “Even in the darkest of times, we have the right to expect some illumination.”) In her book, Arendt goes on to say that “such illumination may come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time-span that was given them on earth.” That flickering light is all we ever really have and Silton manages to connect it like a beacon to the community around her.

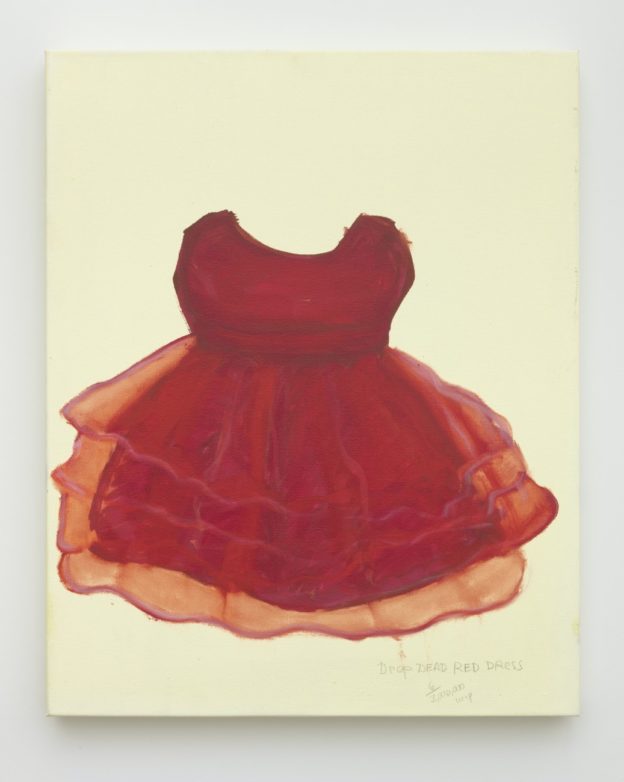

Kim Dingle — Red Dresses and Restaurant Mandalas

Kim Dingle — Red Dresses and Restaurant Mandalas

Sometime mid-year (around the time we once might have expected the final shows in a gallery’s exhibition calendar before summer group shows or the brief summer hiatus when big gallerists and bigger collectors make their way to Aspen or Banff or Italy or Salzburg or Santa Fe), probably around the time we were first emerging from the first pandemic lock-down, Kim Dingle posted a kind of souvenir of a painting on her Instagram feed—the kind of pinafore dress we associated with “Priss” and her pre-school pack of girl-pals—except shorn of its pinafore-puff shoulder sleeves and sleeveless, just slightly longer, layered, elaborated, zhuzhed—and red—the kind of red we wear when we mean to start something. Dingle captioned it as a “DROP DEAD” RED dress—and I didn’t even have to read the rest of her caption—”to wear the day our ‘president’ drops dead.” Perfect mind meld—but that’s the genius of Kim Dingle. I could not get that dress out of my mind. On the one or two occasions I felt up to addressing wardrobe issues (did we really have any anymore?), I strolled through racks of exquisite designer frocks I had not a shred of interest in, only to return to that one red dress in my mind’s eye that I would wear like a Baby Snooks out of the Village of the Damned.

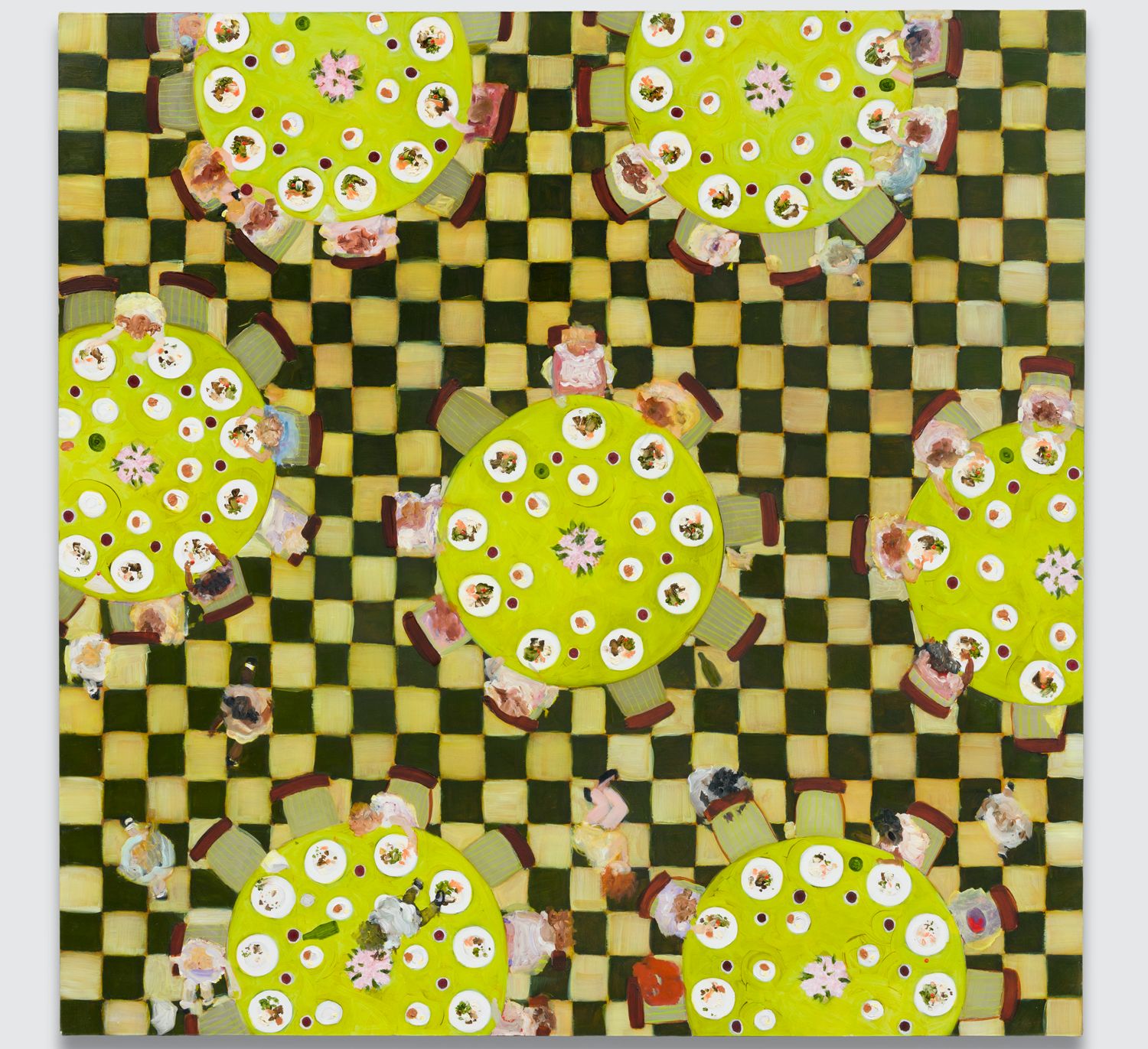

I never found it; and in the meantime Dingle had (of course) moved on, seemingly in a vein both philosophical and nostalgic, with what she called “restaurant mandalas” (at Andrew Kreps in New York)—what evoked (and surely were when they were initiated) restaurant seating and party catering plans. Dingle famously operated a café called Fatty’s in Eagle Rock; and although these paintings felt quite distant from that particular café experience, in their diagrammatic, pattern-and-decoration—spiraling table-settings against the grids of checkered floors — composition, they evoked something of a pre-pandemic attitude — of continuity, of camaraderie, community and hospitality. We miss our girlfriends — and for that matter, the boys, too.

I never found it; and in the meantime Dingle had (of course) moved on, seemingly in a vein both philosophical and nostalgic, with what she called “restaurant mandalas” (at Andrew Kreps in New York)—what evoked (and surely were when they were initiated) restaurant seating and party catering plans. Dingle famously operated a café called Fatty’s in Eagle Rock; and although these paintings felt quite distant from that particular café experience, in their diagrammatic, pattern-and-decoration—spiraling table-settings against the grids of checkered floors — composition, they evoked something of a pre-pandemic attitude — of continuity, of camaraderie, community and hospitality. We miss our girlfriends — and for that matter, the boys, too.

Lisa Adams / Kelly McLane: “Unreality”

Lisa Adams / Kelly McLane: “Unreality”

Is it okay to just say they got there and got it before the rest of us? The dysfunction running like fault-lines through entire societies and not simply their outer limits (though certainly more visible there); dystopian outlooks (and largely human-created, corrupted wastelands); and despair (something that really comes across in Kelly McLane’s paintings and drawings). I had already seen some of the paintings Adams showed alongside McLane’s works at Santa Monica College’s Pete and Susan Barrett Art Gallery, but they still looked so fresh and alive, as did the empathic vibrancy of McLane’s new work—always evolving and finding the ever more precipitous edge.

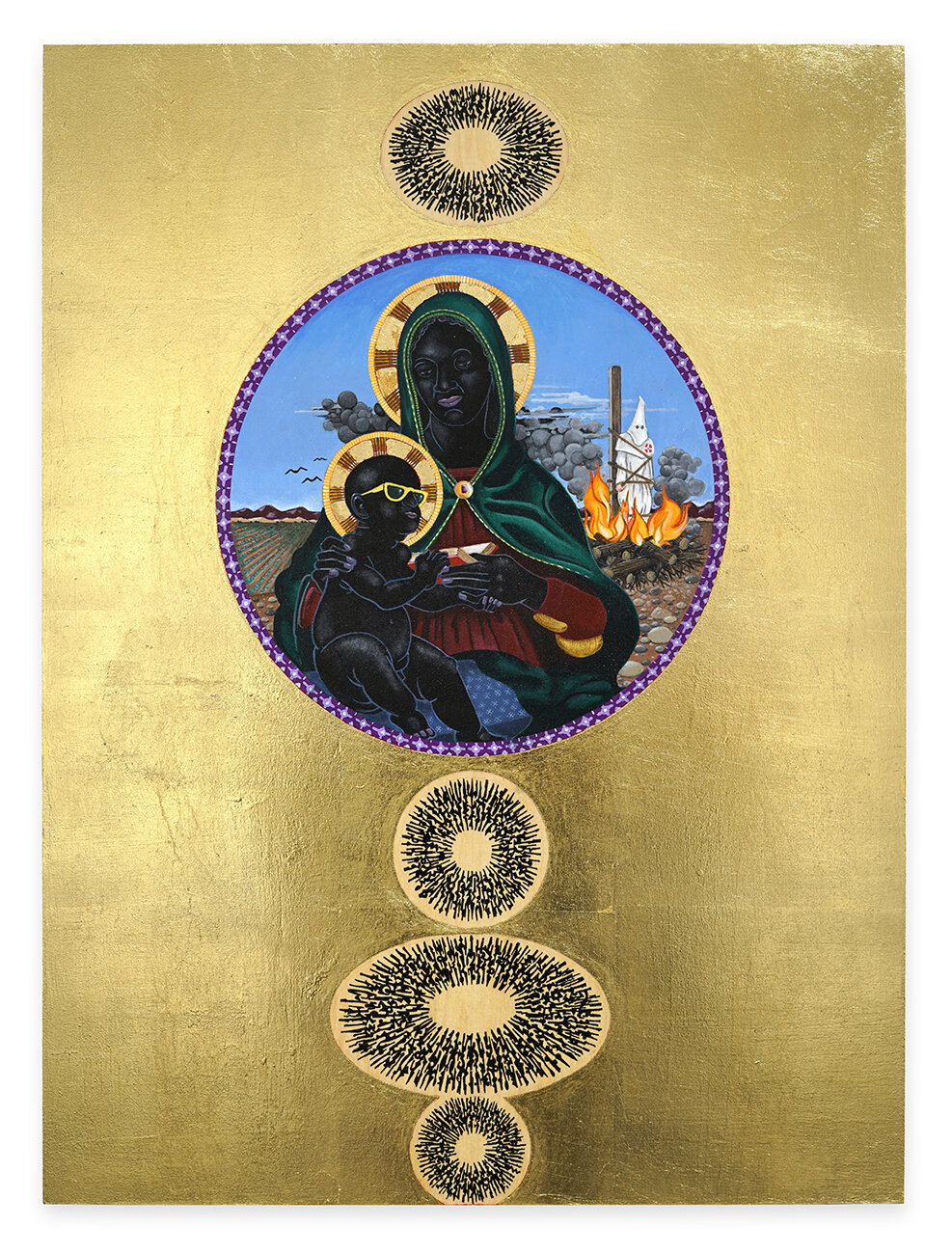

Mark Steven Greenfield: Black Madonnas

Mark Steven Greenfield: Black Madonnas

As anyone acquainted with Greek Byzantine, Russian (and Turkish) icons knows, some of the depictions of their saintly subjects are quite darkly complexioned, which makes some sense given their original inspirations. So it’s easy to understand how Mark Steven Greenfield might have been inspired to leap to wholesale transmutation of a flock of iconic Madonnas (whether actual icons, icons of art history, or icons entirely reconceived). These were all wonderfully rendered (at the William Turner Gallery where I saw them), but also brilliantly re-imagined and re-contextualized, encompassing not simply mythic or historical references, but willful revisions and corrections to those dark legacies (the largest and most encompassing of these being simply white European racism and brutality, especially as replanted on American soil). What’s particularly wonderful about these paintings is the darkness they encapsulate about the infernal machine of civilization yoked to life’s eternal cycles, even in its most tender moments.

Yuja Wang, February 18, 2020, Disney Hall

Yuja Wang, February 18, 2020, Disney Hall

Before she even stepped onto the stage at Disney Hall that Tuesday evening, Wang announced over the auditorium’s PA that she would play the program in exactly the order her mood dictated, without regard to the printed program. She opened with a sonata by the proto-classical Venetian, Baldassare Galuppi, that unfolded like a prayer in delicately arching C major fifths and sixths before plunging into the dark, glittering waters of Ravel’s Une barque sur l’océan, then laid into Alban Berg’s Opus 1 Sonata in a way Thelonious Monk would have instinctively connected with. Then on to the Scriabin F# major sonata and the ecstatic fireworks to ensue; Chopin, Mompou, Brahms, more Scriabin — and, well you get the picture. Wang is already a pianist of legend (perhaps the Argerich of her generation), with any number of celebrated concerts and recitals under her Leger ‘bandages’; but some dates simply soar into unimagined stratospheres, and this was one of them. In only a month Los Angeles would be going dark, but this was a musical performance to keep one’s spirits aloft for the rest of a very dark year.

Boris Giltburg

Boris Giltburg

I’m always discovering new pianists (mostly of the jazz and classical variety), and Giltburg is my discovery of 2020 (not that he hasn’t been around for quite some time). What hooked me was an amazingly leisurely yet gorgeously articulated and ever-so-romantic rendering of the Rachmaninov 3rd piano concerto. Someone compared him (disfavorably) to Alexis Weissenberg and Sviatoslav Richter (both incomparable masters it must be acknowledged); but this entirely misses the point of Giltburg’s performance of style. This is another kind of barque sur l’océan, or maybe just a blanket of romance, and was I ever ready for it. You will never hear those harmonics and sonorities in quite the same way after this immersion. You should check out his renditions of the Rachmaninov Opus 39 Etudes-Tableaux and the Corelli Variations, too.

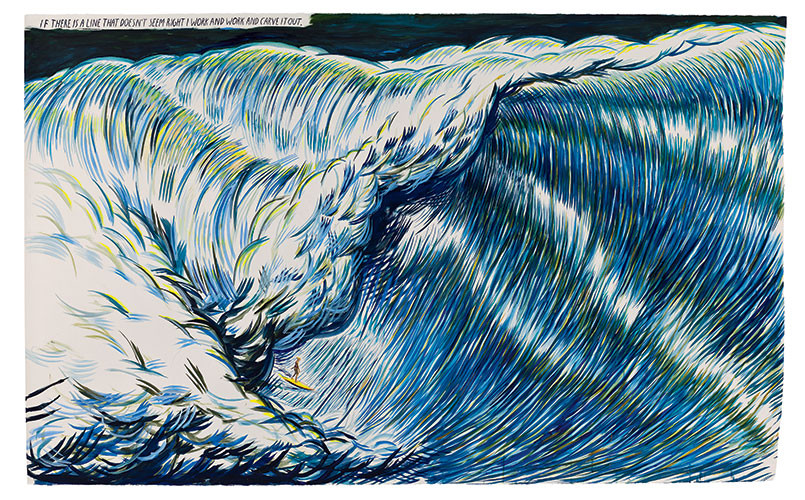

Raymond Pettibon: Where the surf is up per omnia saecula saeculorum.

Raymond Pettibon: Where the surf is up per omnia saecula saeculorum.

Oh—and I almost forgot one: my favorite Person of 2020:

Stacey Abrams: She saved constitutional democracy in America.

Stacey Abrams: She saved constitutional democracy in America.

Now it’s up to us to save everything else.