The last time I was bowled over by an artist’s installation was Damien Hirst’s Theories, Models, Methods, Approaches, Assumptions, Results and Findings at Gagosian, New York in 2000. I have just seen and felt the bar raised again. The artist doesn’t live in New York or London, but in Philadelphia. And the artist is not showing in an upscale art fair in Los Angeles, but in Pittsburgh. Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil installation is an epiphany. It is a wonderful manifestation of curator Ingrid Schaffner’s refreshingly idiosyncratic theme or intention for her 57th installment of the Carnegie International, ‘museum joy.’ Schaffer says, “The aim of this International is simply to inspire museum joy. Simply put: the pleasure of museums comes from the commotion of being with art and other people actively engaged in the creative work of interpretation. Draw on what you know.”

Running from October 15, 2018 through March 25, 2019, the Carnegie International is the second oldest international contemporary arts exhibition. The initial impulse of having this survey was to advance international understanding with a bilateral process of North American and European curators working and consulting together. To curate and select artists, Schaffner worked with “companions” Magalí Arriola (independent curator, Mexico City), Doryun Chong (Chief Curator, M+, Hong Kong), Ruba Katrib (Curator, MoMA PS1, New York), Carin Kuoni (Director, Vera List Center for Art and Politics, The New School, New York), and Bisi Silva (Founder and Artistic Director, The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, and sadly, passed away on February 12th of this year at the age of 57) who added to Schaffner’s international research by each traveling with her to destinations new to them. This was the bilateral process desired by Carnegie and carried out by Schaffner in a unique way. Presenting work by 32 artists and artist collectives, the exhibition invites visitors to explore what it means to be “international” at this moment in time, and to experience museum joy in doing so.

To navigate Schaffner’s final concept, there is a smart, scholarly, pleasure-to- read Guide. It is accessible, friendly, doesn’t talk down and also takes the place of absent didactic wall labels. It was refreshing wandering the Carnegie Museum, not being told what to think, or reflexively reading the label first and looking second. Instead there was the joy of following the loosely laid out trail, making discoveries, finding connections, taking breaks, reflecting, reengaging, all without the usual props and instructions. There were guides in each gallery, elaborating on the work. And if needed, kiosks in the museum where friendly people (true, they were friendly) would answer any questions you asked about the show.

Walking up to the museum there is an auspicious beginning. El Anatsui’s monumental installation, Three Angles, made of folded off set printing plates meshed together with one of his signature bottle cap tapestries traverses the entire exterior façade of the museum entrance. It is an out of the box effort by this major artist who doesn’t hold back. We are used to seeing his brand, and he breaks the mold for this commission.

“Three Angles,” 2018, El Anatsui, Courtesy the Artist and the Jack Shaiman Gallery, Photo by Bryan Conley

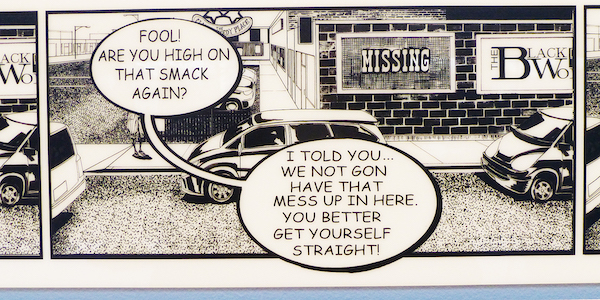

Walking inside, Kerry James Marshall (and an alumni of Otis College of Art in LA) exhibits his complete comic series, Rhythm Mastr that stretches across 70 feet of wall space. First shown in part during the 1999 Carnegie International, it comes full circle with its most up to date incarnation.

Detail from “Rhythm Mastr,” 2018, James Kerry Marshall, Photo by Clayton Campbell

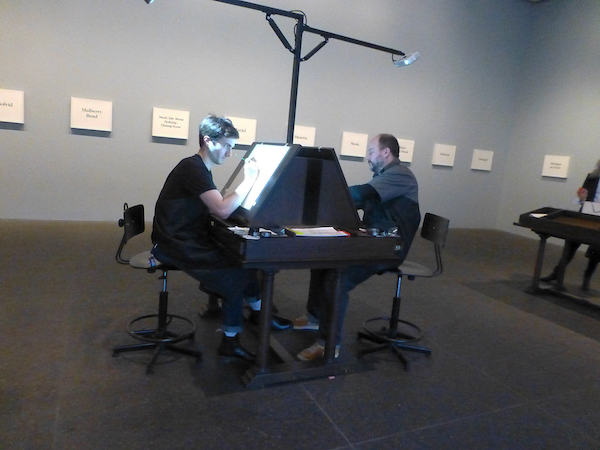

Adjacent Marshall is one of the crowd favorites, Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin. Their participatory installation, Fruit and Other Things, needs a context. Between 1896, when the first International opened, and 1931, the Carnegie Museum of Art made open calls for submission by artists for each edition and rejected a total of 10,632 paintings. Records of the unwanted pictures, along with the artists and the dates they were painted, were kept and remain part of the museum’s archive. Clayton and Rubin have hired sign painters to sit in the museum and hand paint the titles of each rejected picture in alphabetical order. These works on paper are then displayed briefly in the galleries and handed out to visitors for free, along with documentation about the original artist and date. You are asked to take one home, frame and photograph it, then send the photo back to Clayton and Rubin, completing the circle.

Installation view from “Fruit and Other Things,” 2018, Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin, Photo by Bryan Conley

Cameroonian cultural worker Koyo Kouoh’s Dig Where You Stand brings together artworks, books, and artifacts from the collections of the Carnegie and the Natural History Museum in her excellent show within the show. Kouoh’s project researches the archives and collections of the museum to reflect on coloniality, a concept much in fashion and in other hands might have not led to the provocative and insightful conversations Dig Where You Stand can. Her sensitive and smart juxtapositions of objects and artworks are grouped into three sections, Coloniality & Agency, Speculative Temporalities, and Mobility and Exchange. They deliver on the promise to “prompt dialogue among objects and suggest thematic connections that pervade the whole museum.” Just one example of a potent juxtaposition is Cecil Beaton’s coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, an Egyptian relief of Isis, and a 1968 Beauford Delaney portrait of Carnegie patron Tillie S. Speyer. The power of the women is affirmed yet its potential abuses questioned. One takeaway, which is hard to forget is a bald eagle with glass eyes lying in a case, shot down during the Battle of Gettysburg. On another wall a Kara Walker drawing dominates. The viewer’s head begins to spin in a constructive manner.

Installation view from “Dig Where You Stand,” 2018, Koyo Kouoh, Photo by Clayton Campbell

Upstairs in a long, ungainly hallway are the funky paintings, ceramics, videos, and dresses of Beverly Semmes and do they cheer the place up! It is fun to walk down this corridor and see an artist strut their stuff. Quirky chiffon fabric flutters off the wall. Slacker-style, bent, fluorescent colored ceramic pots are spread around, attempting to regain their form from the gravity pulling at them. Videos of nerdy models in funky clothing pass in and out of view. Everyone is having fun in a fashion show that feels like Betsey Johnson on acid. Beverly has been at Shoshanna Wayne Gallery in Santa Monica of late, and doesn’t disappoint.

Installation View from “Feminist Responsibility Project,” 2018, Beverly Semmes, Photo by Clayton Campbell

There are many more good artists in this survey. Yuji Agematsu’s tiny sculptures made of everyday debris picked up on one of his daily walks are obsessive and like Japanese packaging, beautiful. Thaddeus Mosley’s totem-like wood sculptures that hold a deep resonance and commanding presence in their indoor/outdoor settings are quietly majestic.

Saba Innab’s work, an abstract ruin of concrete and steel that mimics a tunnel dug out by the embattled citizens of Gaza, is installed adjacent the Greek sculptures, and this juxtaposition makes the work poignant and disturbing. British hotshot Jeremy Deller has installed tiny television screens into the museum’s permanent galleries of miniature period rooms. They are funny and mildly intrusive. Karen Kilimnik’s humorous and sly interventions of her quirky paintings and objects insinuate themselves into the decorative arts collection, and feel right at home. Mel Bochner’s one-liner text paintings are playful, punchy, and can be a lot of things to lots of people. There are many more; the books as art installations of Dayanita Singh, or the wonderful ceramic wall installation by Sarah Crowner.

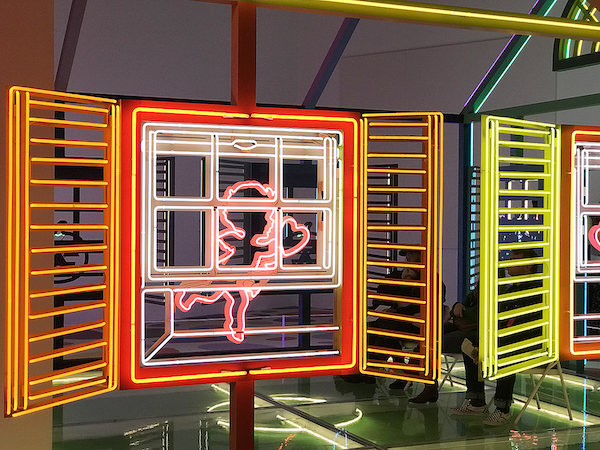

But let’s get to Alex Da Corte. He had a show at Mass Moca in 2016 with lots of neon, brash colors, baubles decorating surfaces, some damn good video work, interesting Queer art, collaborating and mashing in the work of his friends and their alter egos. He has been coming on strong and is sought after for a budding post pop formality. MassMoca was a jump for him from where he had been. Sometimes that is what it takes, giving an artist the platform they need to stretch themselves so their ideas leave the realm of the conceptual and make that leap. With his commission for the Carnegie International, he has made another, more quantum leap with work that is so good, so magical, that everyone who sees it remembers it.

Andrew Russeth, writing in ArtNews on October 15, 2018, said the following, and I agree and love the way he writes about Da Corte: “ It is the best work in the show, and one of the most thrilling I’ve seen in recent years—the rare example, in this International, of an artist swinging for the fences and hitting it out of the park. A giant Heinz bottle is jumping around, freaking out because it’s holding a lit stick of dynamite. The Wicked Witch of the West is singing LeAnne Rimes, improbably accompanied by Oscar the Grouch. Bugs Bunny is sitting on a cartoon crescent moon, crooning Frank Ocean. Then, as ambient music plays, Da Corte walks slowly through the door of a familiar looking set. He’s dressed as Mister Rogers (who shot his children’s TV show nearby), wearing one of his brightly colored sweaters, smiling warmly to the camera and sitting down to change his shoes. Pretty soon he’s out the door, returning a moment later in a different sweater, switching his shoes once more and departing. He does it again and again, arriving each time in a new sweater and with the same joyful hello to the audience. It’s by turns hilarious and sad, and more than a little dark, but as he keeps going, something else happens: it begins to have the feel of an epic. It’s moving—heroic, even. He—Rogers, Da Corte—is striving to get the job done as well as he can. Like us all, he’s putting on his best face, trying to get through the day.”

Installation view from “Rubber Pencil Devil,” 2018, Alex Da Corte, Photo by Clayton Campbell

Installation view from “Rubber Pencil Devil,” 2018, Alex Da Corte, Photo by Clayton Campbell

Installation view from “Rubber Pencil Devil,” 2018, Alex Da Corte, Photo by Clayton Campbell

And there you have it. The bar has been raised, and you can experience it for yourself at the Carnegie International through March 25th. Go feel some museum joy. No hustle, no agenda, nothing to prove, nothing to put a price on. Just for the love of art, the artists who make it, and people all around you digging it.

Clayton Campbell is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles, and his latest E-Publication of photographs, short stories and commentary, Tales From the Downslope; But Picking Up Speed Really Fast can be downloaded at; www.claytoncampbell.com/book-store/