Thérésa Tallien, the French Revolution’s ‘it’ girl, knew how to manipulate perception. Once an emblem of revolutionary glamour, she played the game until it turned against her. Even in captivity, awaiting execution, she refused to become a simple object of pity. The mirror sent to her cell each day wasn’t punishment; it was a tool. Stripped of adornment, starved, pale, she studied herself—not to break, but to refine the performance. When she emerged from prison—freed in part by the influence she still held—she did so as a legend, the Notre Dame de Thermidor, not just a survivor but the architect of her own spectacle.

The sad girl isn’t merely suffering; she’s a tragedy calculation—a negotiation between vulnerability and control. Contemporary Thérésa Talliens understand this too, but where her pain was instrumental, ours is a recursive, self-consuming loop. She is an embodied contradiction, unsettling rather than sympathy-seeking, forcing us to ask if vulnerability can ever be sincere in a world that feeds on it. To be a sad girl is to cultivate a wound. But is sad girl art subversive or exploitative? That binary is too neat.

Recently, I’ve been noticing a promising momentum, particularly in L.A. The era of women draping themselves in gauze, staring mournfully at the viewer, and calling it subversion—what I’d dub Francesca Woodman cosplay—is beginning to dissolve. In lieu of it, a new energy is rising: young women artists taking the fragments of that aesthetic and pushing it into raw, urgent terrain. No longer a vanishing act but an occupation.

Martyrdom isn’t inherited; it’s rehearsed. My generation of young women artists and writers has learned the performance well. Knees bruised, lips cracked, we braid each other’s hair before dawn, praying to our lace-dressed martyr, impaled on the family’s iron fence. The Virgin Suicides’ youngest Lisbon girl—caught between innocence and annihilation. We learned from the saints; ribs cracked open in ecstasy, martyrdom mistaken for holiness. We practiced in secret—pressing our fingers to candle flames, writing bad poetry in the margins of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. I still wake in vintage slips, lingering in the high of the aesthetic, the strap slipping from my tiny shoulder. Playing the role of the pale, femme poet in my own cinematic world. I once went by Luna (not my name), defaced library books with my poetry (sorry), wore Catholic school saddle shoes (though I didn’t go). I wanted a self-mythologizing ritual, a transformation of fragility into potential, rendering the distinction between endurance and performance irrelevant. But I no longer mistake aesthetic for intention. It’s not about discarding the performance but knowing when to break script.

Shannon Cartier Lucy, Woman in a Trench Coat, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Shannon Cartier Lucy’s work offers a window into this realm of self-mythologizing. Her work consists mostly of paintings of figures that I would also cast as “pale, femme poets.” In the piece Woman in a Trench Coat (2018), the slender figure dressed in an immaculate white coat smiles at something out of frame. Her expression is the divine balance between absurd humor and placid derangement. However, the pivotal part is following her hands as they clasp around her throat. It reads as a solitary moment in the muted tones of a blurred-out, lush landscape with casual self-inflicted violence. Cartier Lucy’s figures do not collapse under the weight of their fragility; they shape it into something deliberate, like violence that contrasts her pristine vintage trench coat for spring. It is a sculpted aesthetic that both performs and resists commodification. But it is not just a commodification of pain; it is a ritual. Saint Teresa’s visions of ecstasy were spiritual, but they were also deeply theatrical. She staged her suffering, perfected the pose of rapture. Marking this approach to more of a tradition than a marketable trend. It is a form of belief. Not in the pain itself, necessarily, but in the way it structures identity, gives shape to the formless ache of being.

Los Angeles-based artist Shana Hoehn explores the tension between bodily destruction and transformation in her paintings and sculptures, as seen in her recent solo exhibition at Make Room this February. Her figures twist, they fold, split, and splinter; they expand into grotesque acts of self-transformation. Her consistent use of braids—common symbols of femininity across the girlhood spectrum from sister-wives of Fundamentalists to cheerleaders—morph into something even more insidious than those examples. They become their own phallic ligament, cracking like a whip, poisonous vines of nightshade constricting and consuming. Like the sad girl, they exist in a space of paradox—a familiar image warped into something dangerous and potent. Her girlhood limbs and parts are devoured by infinite orifices, the desire to eat oneself or be swallowed. They ask us to reconsider girlhood, not as something passive or innocent, but as something capable of great violence, both external and internal.

History and literature are littered with sad deities who blur the line between suffering and dominance, their actual power forged through their own undoing with a side of carnage.

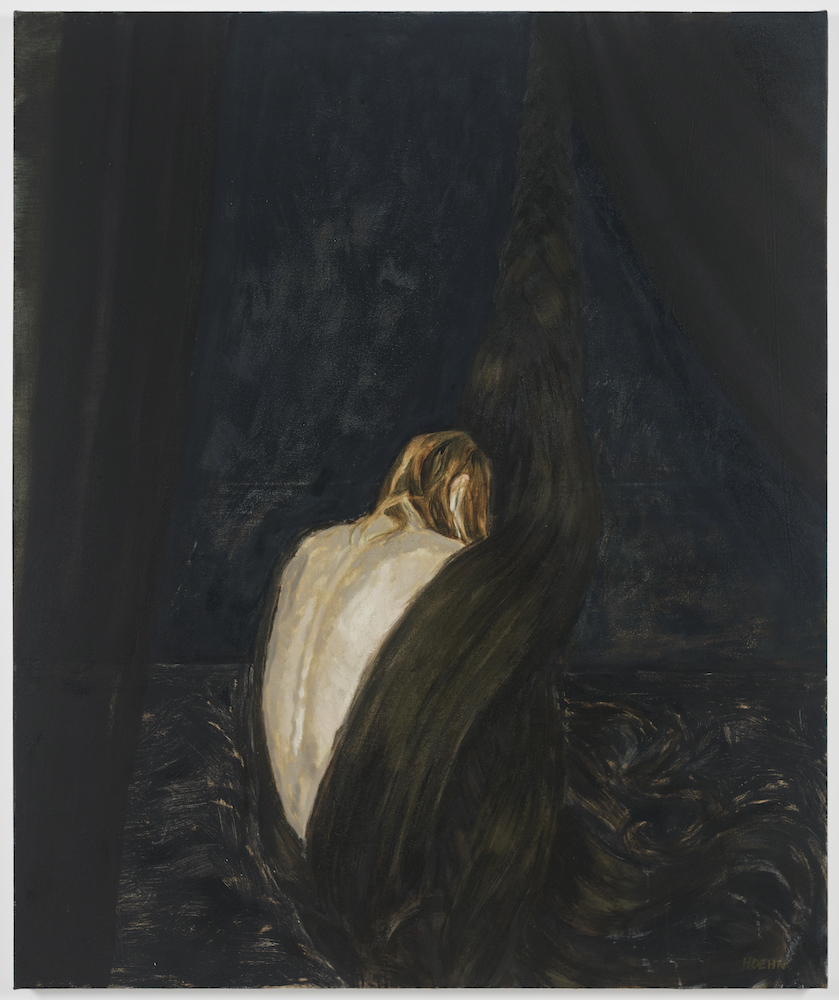

Shana Hoehn, I give birth to myself, 2025. Photo: Alex Delapena. Courtesy of the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles.

Perhaps in the background of Hoehn and Cartier Lucy, who challenge conventional narratives of femininity and girlhood, is Unica Zürn’s work, shaped by the fractured psyche of mid-century Europe, confronts suffering as a transformative force. Her life—marked by mental anguish, violent relationships, and a tragic end—becomes part of a larger, transcendent presence. Zürn’s self-portraits, such as Self-Portrait (1965), capture the body in states of continual metamorphosis. Rather than remaining static, her works unravel suffering, converting it into a force that reshapes identity. Pain becomes a continuous flux, an evolving process where boundaries blur and the self is perpetually remade.

Anne Carson writes of emotion as a force that moves ahead of itself—perhaps madness. But madness is not formless; it is a ritual as old as myth itself. Dionysian ecstasy, Orphic descent. Virgin Suicide. To feel is to be cast into the jagged contours of history, where suffering is spectacle. But in this situation, the storyteller holds the power. Carson’s heroines—Herakles’ wife, the girl burned into glass—are not merely figures of endurance; they become icons, their pain transforming into a legend that cannot be undone. In Hoehn’s I Give Birth to Myself (2025), the figure emerges from a tangled weave of hair shifts between confinement and release, offering no clear-cut narrative of exploitation or subversion. Hoehn’s work speaks to a rupture in the binary, where vulnerability becomes both a prison and a moment of radical emergence. Zürn’s work similarly fractures the body, not as a passive victim of history, but as a dynamic force, subject to reinvention. for both artists, suffering becomes an act of disintegration and reconstruction—history rewritten not by overcoming trauma, but by remaking the self through it.

In Cruel Optimism, scholar Lauren Berlant suggests that when suffering becomes ingrained in culture, it shifts from being personal to collective—so familiar it almost becomes aesthetic. Cartier Lucy’s Bathtime (2018) captures this with a woman submerged in water, her face buried in her hands, her black dress darkening the water around her, as if we are witnessing a casual but cursed domestic baptism. There’s no comfort, no escape—just a repetitive cycle. One set of hands rubs shampoo into her hair, another holds her down, while a third claps to the side. The violence doesn’t lie in any single act; it’s embedded in the whole, as though the entire scene is structured to contain it.

The sad girl was never just an aesthetic; she was a warning. But warnings lose their power when they become too legible, too easy to romanticize. The problem isn’t vulnerability—it’s the way vulnerability has been flattened into a currency, traded in self-conscious martyrdom. The strongest artists refuse this loop. Cartier Lucy’s women, caught between violence and banality, don’t ask for sympathy. Hoehn’s figures contort past recognition, their bodies not symbols but volatile material. Zürn unravels the self completely. These artists demonstrate that, when recontextualized, suffering is not a pitiable condition; it becomes something to fear. This is where the sad girl fractures: when she stops looking at herself in the mirror and starts clawing at the glass.