“Photography; I’ve always loved it,” says Moby, the noted techno-music composer and performer who is also cultivating a reputation as an art photographer. “My mom was a painter, my uncle was a photographer for The New York Times.” When Moby was 10, his uncle gave him a serious camera, a Nikon F, and later some darkroom equipment. He learned to develop film and enlarge his own prints, but for years he was self-conscious about calling himself an artist. “There’s a mixed history of musicians becoming visual artists,” he admits. “Then about five years ago I had a body of work and showed it to my artist friends in New York and luckily they encouraged me.”

That was also when he started spending more time in Los Angeles and bought himself a dream house in Beachwood Canyon. (He’s a serial home renovator, and has gone through several apartments/houses in Manhattan and in upstate New York.) This time he bought a Norman-style castle with turrets and pointed roofs built in 1927 for L. Milton Wolf, one of the developers of Hollywoodland. On the compound is also a guest house designed by John Lautner, added in the 1950s, which he uses as his office/studio and where this interview is taking place.

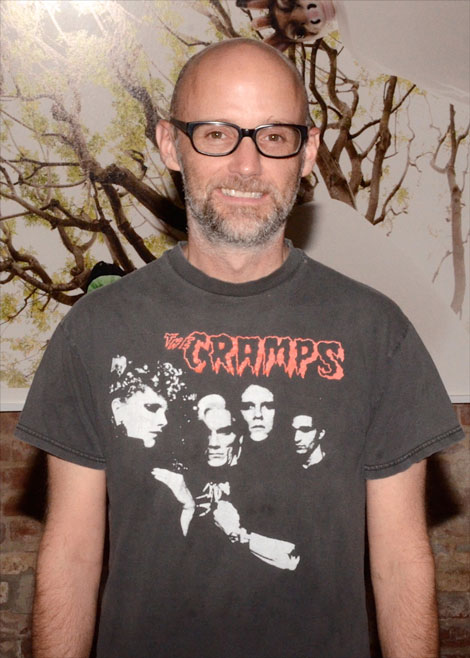

Moby is the stage name for Richard Melville Hall— it’s also a longtime nickname since he is actually related to Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick. A small, wiry man with a shaven head, he is wearing an old T-shirt and horn-rimmed ck glasses. He rarely smiles or laughs, but he does talk easily, in a slow, almost drawling sort of way, as if constantly thinking about the effect of the words that come out of his mouth.

In 2011, he had his first art exhibit in Los Angeles at Kopeikin Gallery. That show, “Destroyed,” featured blow-ups of pictures he’d taken during his concerts around the world: the view from the stage, his view of the teeming masses looking both ecstatic and possessed. A sea of figures waving, shouting, swaying, bathed in eerie rakes of purple, green and yellow light. “I was thinking of the Dutch Masters versions of hell, like the Lake of Hell,” he says. The comment is stated matter-of-factly, but makes you wonder what he was thinking when he was up there playing his guitar or drums. Did he think he was in the Underworld, playing to the damned? “The [exhibit] was a success in that people liked it; it was a failure because it didn’t scare anyone,” he told me.

His second gallery show, also in Los Angeles, “Innocents, New Photographs of the Apocalypse,” took place this spring at Project Gallery, and while the dozen or so very large blow-ups definitely have a dark, somber tone, I’m not sure you would call them scary, either. They were all taken in Southern California—some around his swimming pool, where he shot the music video for the song “A Case for Shame” on the new album, Innocents, that came out last fall—and which to some extent was inspired by the city.

“When I moved to Los Angeles, I got interested in the history of cults,” he says. He refers to the various cults and New Age movements that began or got traction here: “This is ground zero for cults.” He cites predictions for the end of the world in 2012, according to the Mayan calendar (some said). “Nothing happened, but then I started thinking maybe it did. The narrative for this show is that the Apocalypse has happened, and I’ve invented this post-Apocalyptic cult. It’s the cult of innocence, informed by a sense of shame. They look at human history and have a terrible sense of shame over it.” The members of this cult dress up in robes and animal masks, and in one photo they are gathered in a circle over you; this image graces the cover of the Innocents album.

The opening for his show was packed. Moby mixed with the masses (and some celebrities) and complied with requests for autographs. The photographs included dark, moody clouds looming over the landscape and a young girl in the sunshine, running towards the darkness on the left. He refers to the latter as “the angel of the Apocalypse, all the stuff around her is so menacing, this barbed wire and super sharp agave. At first it seems like a lighthearted image, and after scrutiny it darkens… ” (He stages shots, and he used digital alterations.) He clearly likes that edge, where something seems one way but turns out to be another, where light and innocence has a darker, even threatening, underside. “One of the things that art can do is to change people’s quotidian experience,” he says. “I wanted to create this disconcerting narrative.”

All images courtesy Project Gallery