“Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings,” is a deeply satisfying survey exhibition of the photographer’s work which has traveled from the National Gallery of Art in Washington to the Peabody Essex Museum (Salem, MA) and is currently at LA’s Getty Museum.

While attending the press opening, I had a chance to discuss the exhibition with the curator of the National Gallery. She wondered aloud why Mann had not had a major traveling show until this point in her career. Could it be that she was working from a region, the South, outside the art centers of Los Angeles and New York? Or, that her work was disparate in its interests, resisting a brand and digital fashions? I wondered if it were perhaps that there were few opportunities on this major museum level for any artist, and historically less so for women?

What was unexpected was the curatorial selection. Many of the photographs were being seen for the first time. The exhibition of 110 works has been organized into five sections entitled Family, The Land, Last Measure, Abide With Me and What Remains.

Mann’s career and this exhibition commence with what we first knew her for, the iconic photos of her family. The decade-long series included photographs of her children, sometimes staged, and some of which were nude. The controversy that swirled around Mann in the Spring of 1992 with the publication of the book, Immediate Family, was intense, coming on the heels of Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ uproar and the Robert Mapplethorpe firestorm, with the Corcoran Gallery exhibition cancellation and the Contemporary Arts Center of Cincinnati being brought up on obscenity charges.

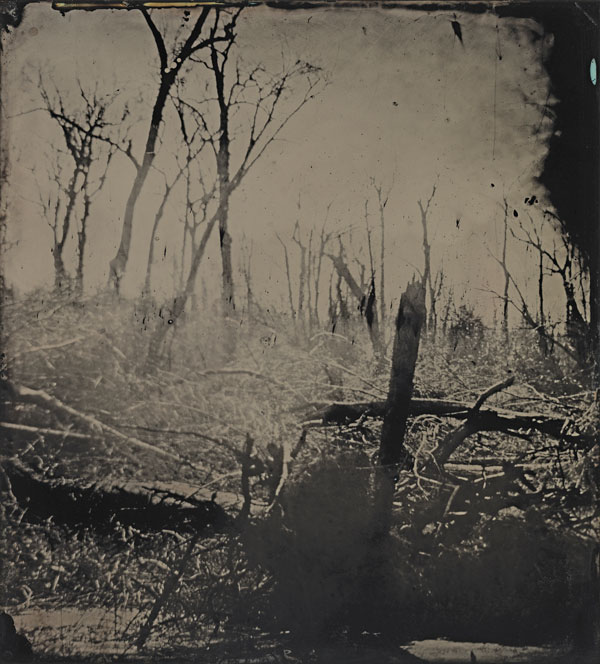

Battlefields, Antietam (Black Sun), 2001.

Much has been written about these photographs and Mann’s personal responsibility or lack there of to her children, their welfare, as well as issues of child pornography. But by 2001, when Time magazine named her “America’s Best Photographer,” it stated: “Mann recorded a combination of spontaneous and carefully arranged moments of childhood repose and revealingly—sometimes unnervingly—imaginative play. What the outraged critics of her child nudes failed to grant was the patent devotion involved throughout the project and the delighted complicity of her son and daughters in so many of the solemn or playful events. No other collection of family photographs is remotely like it, in both its naked candor and the fervor of its maternal curiosity and care.” Historically tolerance and censorship ebb and flow in cycles, governed by the prevailing moral politics of the moment. Looking back across two decades we wonder about the controversy and see the art.

Mann spoke in an interview with Terry Gross of NPR’s Fresh Air in 2015 about the controversy. She “was surprised by so much presumption in people’s reactions.” The artist didn’t seek out this controversy, and sees the photographs as what they technically are, 1/30th of a second captured on a piece of paper. “They are not children, they are photographs.” Fiercely protective of her family, “I never separated myself as an artist and a mother. …When I saw their bodies and photographed them, I never thought of them as sexual, I thought of them as simply, miraculously and sensuously beautiful.”

Mann did not go to art school, but has a masters degree in literature. She studied photography at Bennington College with Norman Seeff, but says she never reads about photography. Her iconoclasm seems to abound in A Thousand Crossings with her deference to black-and-white and monochromatic printing. Only five images are in color. Her absorption in the craft of photography is monumental and pervasive in a way rarely seen in digital age. Her devotion to the craft of photography includes references to the craft-centric Pictorialism movement of 1900–30. For example, she relies on an old 8 x 10 view camera and experiments with antique lenses. She liberally uses the antique collodion wet-plate process for making negatives to achieve accidental painterly effectives akin to nonobjective painting. She has experimented with 19th-century tin-type methodologies to achieve deep blacks and liquid smears for particular images. Her practice is to shoot mainly in summer and print the rest of the year in the darkroom. As a printer she is extraordinarily deft and creative.

Easter Dress, 1986.

After the Immediate Family photos, Mann evolved to what she describes as “deeply personal explorations of the landscape of the American South, the nature of mortality (and the mortality of nature), intimate depictions of my husband and the indelible marks that slavery left on the world surrounding me.” The exhibition’s next section, “Land,” is a preternatural view of the South’s landscape and the deep tensions it still holds. Large in scale, dark and sepia-toned, I wonder if the older techniques she employs create historical baggage or author something new, authentic, honest?

The image, Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie) from 1998 seems to suggest something nostalgic, until you read the wall label that says this is the bridge from which Emmett Till’s murdered body was thrown. It is jarring, traumatic and ghostly, filled with the abject horror of this terrible American crime, yet deeply respectful.

I was struck by the third section, “Last Measure.” These large prints from the Civil War battlefields of Antietam from 2001 are dark and mesmerizing. The point of view is that of perhaps a soldier, lying face down, bullets whizzing by, straining to see as the last light of reason flickers out in a blasted landscape. The work seems prescient, given our current socio-political realties. A New Yorker article from 2017, “Is America Headed For A New Kind Of Civil War?” came to mind as I was looking at “Last Measure.” The article posited that conditions nurturing conflict around the globe can now be seen at home. Most civil wars of today are low-intensity conflicts with episodic violence in changing locales—unlike what we experienced in 1861–65. Nevertheless, the final, awful legacy of the Civil War, as Mann’s photographs suggest, with their absence of violence as the evidence of the unspeakable, is that it can happen here again if we are not careful.

Blackwater 13, 2008–2012.

Her work is indebted to the South, and the history of blood and bones it carries deep within the body of the earth. “Landscape” for Mann is about the way place shapes people. In the fourth section “Abide With Me,” the artist seeks to come to terms with race, history and the land as a contested site of struggle, survival and shifting memories. Her “Blackwater” series of tin-types is brooding and visceral, photographed in the Great Dismal Swamp where Nat Turner and other fugitive slaves hid before the Civil War. The section continues with a room devoted to small photos of turn-of-the-century African-American churches, when African Americans were first free to worship without whites overseeing them. The gallery is filled out with images of her parents’ African-American housekeeper, Virginia. She was a clearly beloved figure for Mann, and how Mann first came to know the profound discrepancies and gulfs in race relations in the South.

The body is the vehicle Mann returns to again and again. Four moderately scaled portraits of African-American men are included. These were done after Mann was inspired by the choreographic work of Bill T. Jones that keyed on the black body as the site of stereotyping, exploitation and violence towards African Americans. As a white woman, born in 1951, Mann has an unflinching desire to understand “the seemingly untraversable chasm of race in the American South.”

The final section is called “What Remains,” and manifests her lifelong fascination with themes of mortality, death, decay, love and hope. This cycle of life and regeneration threads beautifully throughout this final section. It has large-scale photos of her children’s faces, described as hopeful images as she lets go, no longer youthful, intimate, or black and white.

They are expressionistic and ethereal. There are two composite self-portraits taken after Mann experienced a serious riding accident and broke her back. Aging and mortality became an immediate issue for her. But most notable perhaps is one of her favorite bodies of work, images of her husband who suffers from muscular dystrophy—a large, powerful former blacksmith, whose body is seen through a haze of distressed surface and painterly accident, as her technique as a photographer and printer touches a special moment of sensitivity. She says of this work, “It began as documentarian and then became art, it makes weakness revelatory.” It was work she and her husband could do together, and were “incredibly happy times, lovely moments in their marriage.”

They are still together. Sally Mann continues to live and work in Lexington, VA, as she has for the past 45 years.