There’s something in the Los Angeles air recently that’s been conjuring the ghost of Charles Manson. He has been coming up in conversation frequently (or maybe I am bringing him up). California’s back on the national stage for its hippie-turned-fascist tendencies. Utopian visions morph into murderous cults à la the Zizians. The inherent contradictions of the “Golden State” are getting blown wide open. Another possible culprit for the Manson discourse: Michelle Uckotter’s show “Moviestar” at Matthew Brown.

At the opening of “Moviestar,” everyone is asked to remove or cover their shoes before stepping on a grimy mustard yellow carpet. I get a whiff of cigarette and briefly wonder if the smell is real as I seem to be within some sort of 1970s set (crowds of people are in fact smoking inside). Sculptures of cardboard boxes with chandeliers haphazardly tumbling out are situated in the room like discarded props—and I catch a glimpse through the crowds of a striking Uckotter painting.

“Moviestar” at Matthew Brown is just one segment of Uckotter’s takeover (the darling of Frieze week!) of Los Angeles, the others being an identically titled show at Marc Selwyn and a video screening at Now Instant theater in Chinatown. Uckotter has traded in her paintings’ previous recurring attic setting for a middle-class mid-century living room, or perhaps we have simply wandered downstairs. At Matthew Brown, we are in a living room, stepping on its carpet, looking at paintings of a similarly carpeted space. What unfolds in the paintings, adapted from stills from the video, is a night gone off the rails, a crime scene, or maybe just a dark and twisted sexual fantasy. The women of “Moviestar” are in compromising positions, but whether licking a gun, tied up, or doing the tying up, they emanate a manic power.

I call them paintings because the work does contain oil paint, but Uckotter’s scenes on panel lie somewhere in between drawings and paintings. Pastel is layered atop oil paint, and scratchily articulated figures that from a distance snap together, turn into a controlled chaos of lines and scribbles close up. The oil pastel is waxy, and while matte from straight on, it catches the light when the viewer shifts angles. Paint is treated as if it’s the same substance and emerging from the same tool as the pastel. The boundaries between the two blur, distinguishable only upon careful examination. The sculptural clay-like quality of the pastel produces chalky flecks of byproduct, chunks of which appear at the edges of marks where Uckotter has pressed with great force. Like the white cap of a wave, the excess pastel reveals a turmoil and intensity.

Michelle Uckotter, The Lady with Gun, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

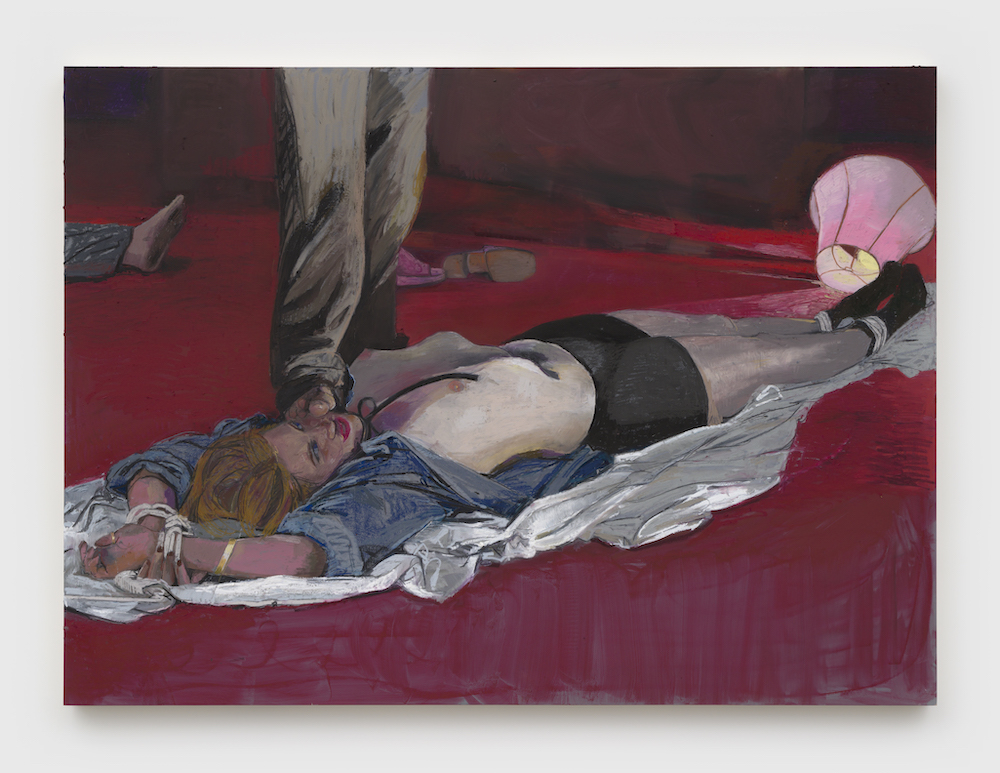

In The Sot (2025), a woman is splayed out, bisecting the frame, hands and feet tied, a foot pressed against her face. Her shirt has been ripped open to reveal a bare chest. This woman is playing to the camera or perhaps the camera is playing to her. Uckotter’s framing is ripe with a lustful gaze. The violence depicted isn’t quite frightening; it’s evident that this is merely a performance. These girls are “movie stars” acting as victim, killer, musician, or psycho. And I don’t know if I quite buy the verisimilitude. While denied access to any straight-on gaze, we have body language and composition to go off of. The subjects are equipped with an unnatural assuredness.

Beyond a few scratches, bodies remain intact or are mysteriously slumped over. The implication of body horror gets absorbed into the surrounding scene and furniture. The saturated red carpet furnishing the floor in the paintings bathe the room in a nefarious bloody glow. Glasses, bottles, and decanters, filled with a syrupy red wine, are strewn about. The dingy, green carpet in Dream (2025) is patterned with pink and magenta rose buds that appear like open wounds, with the surrounding carpet turning a bruised yellow and gray. In The Lady with Gun (2025), a lamp, the shade perched at an angle, drips with spots of red. The red resembles scratches on a body, though it’s questionable whether this is blood splatter or the worn-out shade’s stray threads. It’s not the only disturbed lampshade. In The Sot (2025), a fallen shade sits beside its captive companion. Both shade and figure are pink-tinged, their bodies equally exposed. At Marc Selwyn, a lamp gets its own portrait, in which it lets off a thick, snotty, chartreuse glow.

The Manson murders, the epitomic Los Angeles murder spree of the 20th century, hover over “Moviestar.” What strikes me about the similarities between “Moviestar” and the Manson murders is less visual or temporal—hippies, pig noses, drugs—and more the cinematic collapsing of truth and fiction. The phrase uttered by Hollywood elites in Tate and Polanski’s circles, “live freaky die freaky,” is apt for Uckotter’s girls.

Michelle Uckotter, Dream, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

I don’t quite know how to situate the relationship between the three parts of the show. If Matthew Brown is a bacchanal of decaying femininity, Marc Selwyn offers the grimy masculine, populated by men with sweat-clumped hair and a single female torso nude. The show at Selwyn is stripped down, having exchanged sculptural ornamentation (only a single chandelier here) for a bare-bones display. The operatic Matthew Brown presentation overshadows it, sidelining it as supporting character.

Then there’s the video. I almost didn’t want to see it lest it bring about some kind of narrative clarity. There is some amount of inevitable disappointment at getting access to the paintings’ source material. A committed period piece peppered with strategically placed anachronisms, Moviestar (the video) (2025) follows careerist artistic types encountering a psychotic hippie home invasion. The anachronisms in dialogue and dress pleasantly destabilize the precise set dressing. In the painting “The Threesome,” a man, tied up by two women, sports a knuckle tattoo that says “true.” This paradox, the untruth of a historical inaccuracy that says “true,” speaks to the intent of the project at large. It is collapsing time, fictionalizing historical events, and exposing violence’s manifestation of unconscious fantasies. Etched into these paintings is a truth of sorts.

But it’s only of sorts. What is a director/painter if not a cult leader, promising the truth while delivering an illusion. Pulling the strings, getting others to do your bidding, emotionally molding your underlings. Manic smearings elevated to godly proportions. I’ve joined the Uckotter cult.

Michelle Uckotter: Moviestar

Matthew Brown (and parallel exhibition at Marc Selwyn)

631 N. La Brea Ave.,

Los Angeles, CA 90036

February 13 – March 29, 2025