Any project that attempts to recontextualize history is embarking on a daunting, arduous task. There’s a fine balance between providing too much detail and too little, in particular when the temporal scope of the story is ambitious. Embracing these challenges with confidence and clear mastery of her material is Katy Hessel, who has rewritten art history from the Renaissance to the present day to highlight the women artists who were working alongside and eclipsed by their male colleagues.

The Story of Art Without Men is well researched and expertly told. Hessel, the art historian behind the popular podcast and Instagram called the Great Women Artists, is uniquely positioned to tell this story. She includes succinct context and clear descriptions of nuanced topics—artistic movements, techniques, genres, tropes—gliding through decades and centuries with remarkable speed without giving the reader whiplash. Indeed, Hessel’s consideration of the reader is what makes her writing stand out. She explains art history with enough details to engage novices while avoiding becoming too didactic and risk boring a more informed audience.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Mnemosyne (Marie Spartali), 1868. Albumen print from wet collodion negative. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Andrew R. and Martha Holden Jennings Fund.

The book begins with shocking anecdotes and statistics. A 2019 study, for example, revealed that 87% of the artists in 18 major US museum collections were men. The UK also fares poorly. The National Gallery in London, Hessel explains, only held its first major solo exhibition by a historical female artist in 2020 with Artemisia Gentileschi. Hessel offers additional facts, which are even worse for women of color, and sets the stage for what her book seeks to correct.

Hessel acknowledges caveats on the scope considered here, which is informed by her own studies that centered on a Western male narrative. Painting, for example, is the only medium discussed in the book until the 19th century, when Hessel first mentions others such as quilting, pottery and sculpture. Of course, her commitment to covering over 700 years in some 500 pages leaves inevitable gaps. However, Hessel’s work invites further research without making this additional work a requirement to understand and enjoy the text she’s provided. Additional knowledge—preconceived or studied after the fact—would certainly complement the book, but the text as is keeps the reader interested and informed.

As she embarks on her ambitious task to rewrite art history without “the clamor of men” (p.12), Hessel chooses a handful of women artists to ground each period. The earlier movements in the 16th and 17th centuries are some of the most informative, in which Hessel relies on extensive research to highlight women whose sparse historical records have been pieced together through legal documents and scholarly reports (mostly written by men). In these centuries, the women whose artistic work and influence survived were nearly always associated with aristocracy or had fathers, brothers or husbands who were also artists.

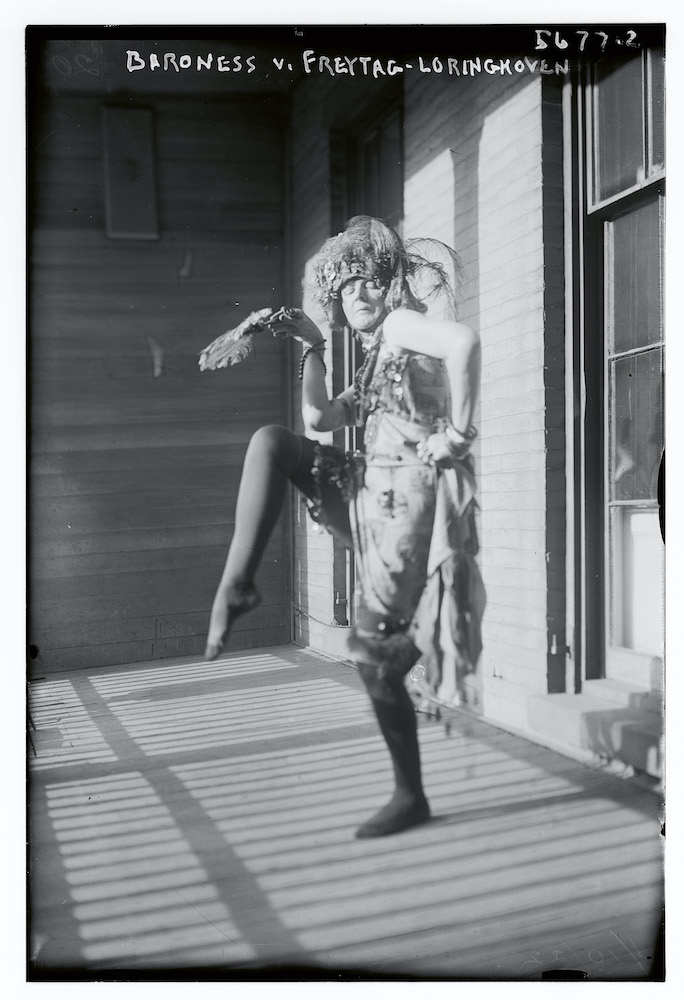

Unknown photographer, Baroness Von Freytag Loringhoven, c. 1920-1925. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

While rewriting history, Hessel takes care to explain why imbalance exists in the first place. She highlights some of the causes for the millennia-long existence of a male-centric art world, including the active exclusion of women from academies and examples of women’s contributions being downplayed, attributed to men, or erased altogether (sometimes by their own hand as women used pseudonyms to ensure a seat at the all-male table). One example in plain sight is Johann Zoffany’s painting The Academicians of the Royal Academy (1771–72), which features the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. All of the 36 members are painted in full portraits—except for the two women, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, who are removed from the group and represented by two barely recognizable busts.

Some of the names in these early years are well known, like Gentileschi, but most will likely be new to any reader—an exciting and welcome opportunity to learn. Unsurprisingly, as developments in women’s rights and access to formal training improved, the number of women artists increased, and their contributions were better recorded. The vast majority of the book is dedicated to the last 150 years and include familiar figures, such as Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Diane Arbus, as well as blue-chip and celebrity contemporary artists, such as Amy Sherald, Yayoi Kusama and Julie Mehretu.

Throughout the book, Hessel’s clear love for the history of art shines. She notes her favorite works and embarks on nuanced, poetic visual descriptions with reverence and excitement, as if discovering her subjects for the first time. It’s these moments that propel Hessel’s text and inspire curiosity. It’s hard to believe it took until 2023 for this book to be written, but it’s clear Hessel doesn’t want this to be the last chapter. On the contrary, The Story of Art Without Men is an invitation to constantly rethink art history and continue to fill in the gaps.