During his year-long residency at the American Academy in Rome, Michael Queenland roamed the streets. Rome is a beautiful city to walk in, filled with ruins and monuments, but like any modern city, it is also cluttered with trash. The detritus—what was thrown away—caught Queenland’s eye and became the subject of his art.

Queenland collected the refuse and transported it to his studio to scan and catalogue. By the end of the year, he amassed a huge archive of over 2500 discarded objects ranging from cigarette packages to balloon fragments, playing cards, grocery lists, post-it notes, scratch cards and flattened wire tops from champagne bottles. What interested him was how these objects mapped the city to become a collective portrait of contemporary Rome. However, Rome is also a city filled with magnificent old churches. These contain intricate mosaics and patterned marble floors. The contrast between these divergent artifacts fascinated Queenland, begging the question: How can a city be so beautiful yet so abused?

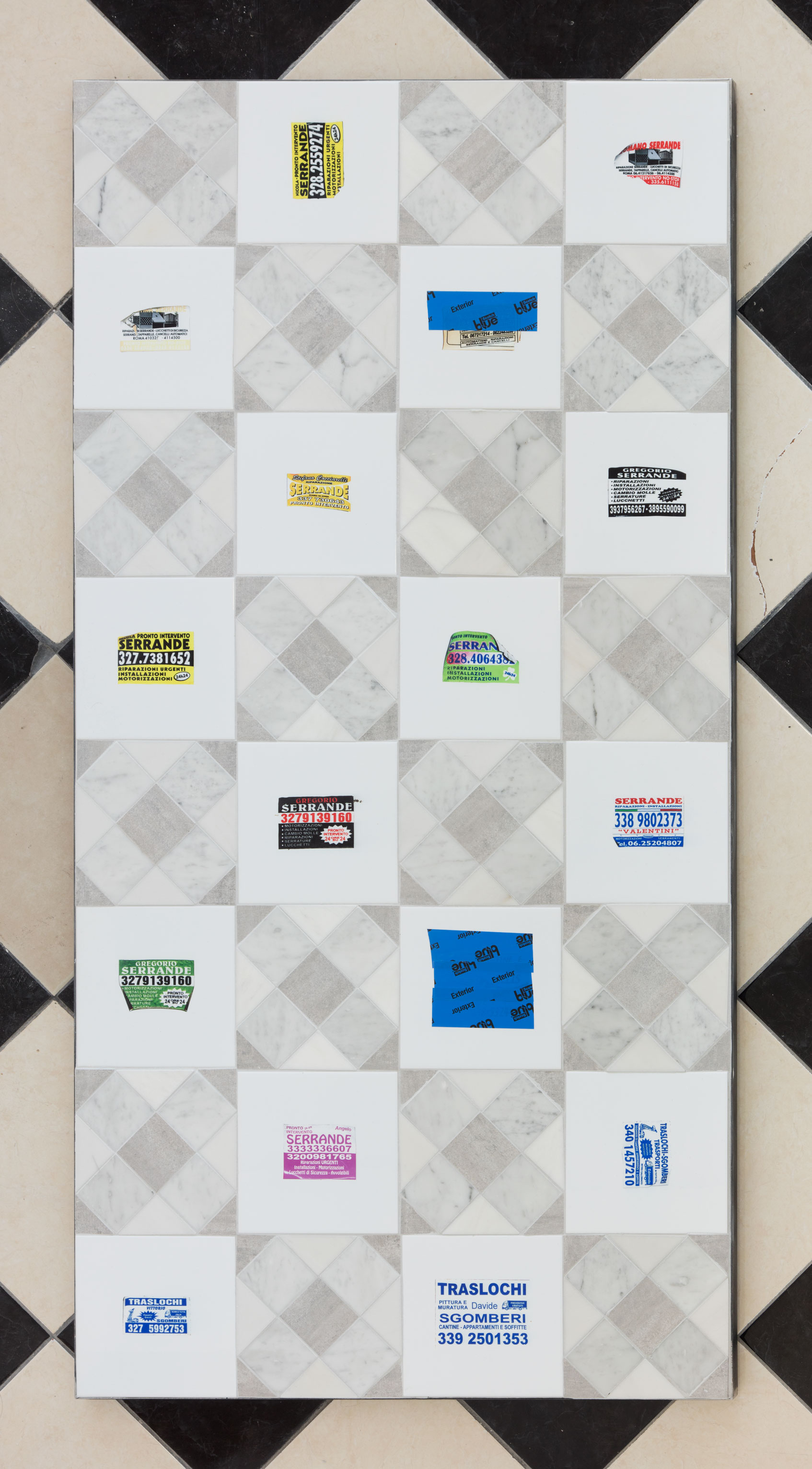

For “Roam,” Queenland created over twenty rectangular floor sculptures measuring approximately one inch high by 32 inches wide, in lengths ranging from 40 to 80 inches. These works are comprised of grids that intersperse eight by eight inch square tiles. Some form patterns made from square and triangular shaped pieces of marble and granite, while others are basic white ceramic, containing a life-sized image of one of the colorful objects Queenland collected and later preserved through scanning. Coincidently, the gallery floor upon which Queenland’s sculptures sit is also a checkerboard pattern of black, white and terrazzo tiles. These flat sculptures partially cover the floor—some are isolated, others connected, forming yet another pattern within the space. They demand to be seen from all directions, requiring viewers to carefully tiptoe in between, making them hyper aware of the similarities and differences between Queenland’s art and the tiled gallery floor.

Michael Queenland, Untitled (Foreign Tongue), (2017), photo by Brian Forrest, courtesy Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles.

Toward the front of the gallery, Queenland situated seven 80 by 32 inch panels arranged to form an architectural shape that only partially covers the floor and calls attention to the contrasting scales and patterns. Adjacent to this cluster of sculptures are two more connected works—Untitled (Services #3) and Untitled (Foreign Tongue) (both 2017) that form a «T.» In Services #3, Queenland embeds sixteen tiles depicting the diverse coloration and typography of cards advertising services whereas in Foreign Tongue he juxtaposes and explores the details of flattened cigarette packages. Other panels contain an assortment of deflated and ripped balloons, as well as combinations of items organized by size, shape and function.

What makes Queenland’s works interesting is the relationship between the torn and mangled found objects and the pristine patterns of the geometric tiles and their divergent referents. The sculptures explore the relationship between ruin and re-construction. They also function as archeological relics that display the fabric of the contemporary urban environment.