Panoramic history paintings depict all encompassing views, often creating a cinematic effect, and require active participation from the viewer, who is surrounded by the imagery. Meleko Mokgosi’s much lauded, multi-panel paintings exhibit a technical mastery that he uses to depict effects of colonialism on the people of Southern Africa. These large-scale works explore the relationships between history and painting; collectively titled “Pax Kaffraria,” they investigate nationhood, post-colonialism and identity via collages of imagery culled from myriad sources.

Mokgosi is schooled in cultural criticism, political and psychoanalytical theory, as well as cinema, and brings these disciplines to bear in his narratives. He also draws from his own history. On every visit back to his native Botswana he sifts through boxes of newspapers his family saves for him. He also peruses magazines and periodicals looking for images of the mundane, the middle class and the depiction of current events to construct scenarios from this source material.

Many of his paintings are carefully crafted multi-panel narratives in which he plans each scene shot-by-shot as if directing a film. Mokgosi storyboards his works, making one or two drawings per painting in which he figures everything out: brushstroke and size, line, shadows, colors, foreground/background relationships. What results is a lushly painted, vigorous melange of disparate images. In the four-panel painting Pax Kaffraria: Full Belly (2014), Mokgosi depicts a fragmented journey through Southern Africa’s recent history. Visually moving left to right across the unprimed canvases one sees a worker holding a part-ram/part-bull on a leash, followed by the depiction of sunglass-wearing officials, and from there the narrative moves to a seated dictator adorned with both contemporary and traditional garments. Next, Mokgosi presents a group of singing women whose faintly outlined bodies meld with their black-painted background. In the final panel, the upside-down meets the right side up—present and past coexisting as a mix of civilian and military personas.

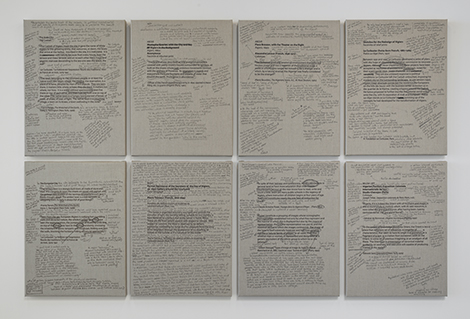

While most of the works are illustrative, Mokgosi surprisingly shifts focus with the inclusion of two text-based works. Walls of Casbah II and Modern Art: The Root of African Savages II (both 2014) are nods to Glenn Ligon’s Condition Report (2000) in which a conservator scrawled the imperfections in the work on its surface. Mokgosi similarly annotates descriptions from the 1914 exhibition “Statuary in Wood by African Savages: The Root of Modern Art” presented by Alfred Stieglitz at Gallery 291 in order to point out contradictions and injustices in the relationships between African and Modern art.

Mokgosi’s project is one of remediation. He makes reference to art, history and popular culture; taking bits and pieces from multiple sources, he conflates them to create works with expansive cinematic appeal but with little to say about anything specific. His seductive works are too prescriptive. They concentrate on piecing together images to make a painting that shifts from one point of view and style to another. While the history and plight of those in Southern Africa are ripe content for his explorations, the works are too distanced and studied to resonate beyond their initial visual appeal.