There’s a scene early on in the film The Night of the Iguana (1964) where Richard Burton, playing a jaded ex-priest-turned-tour-guide in Mexico, asks the bus driver to stop on a bridge. The passengers—a group of American matrons—are puzzled. “What are we stopping for?” one asks. “A moment of beauty…” says Burton, gazing wistfully at the locals on the riverbanks below—women cheerfully washing laundry, children splashing in water. “A fleeting glimpse into the lost world of innocence.”

The director of photography for the film was Gabriel Figueroa (1907–1997), who was by then a 30-year veteran of the film industry. He is also currently the subject of a major and remarkably gorgeous retrospective at LACMA, “Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film” (through Feb. 2, 2014). I knew nothing about Figueroa when I first saw Iguana long ago in some repertory theater. Now Burton’s lines have a poignant ring, for they seem to me also remarkably apt for this exhibition, particularly the first half, when Figueroa was a leading light of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema.

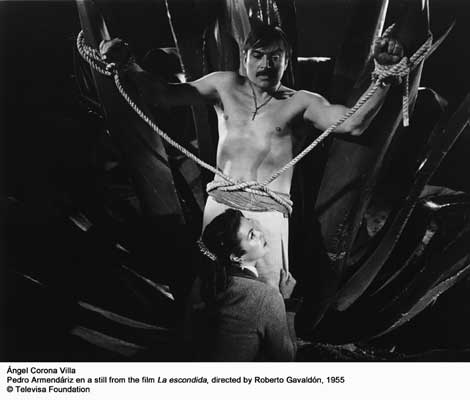

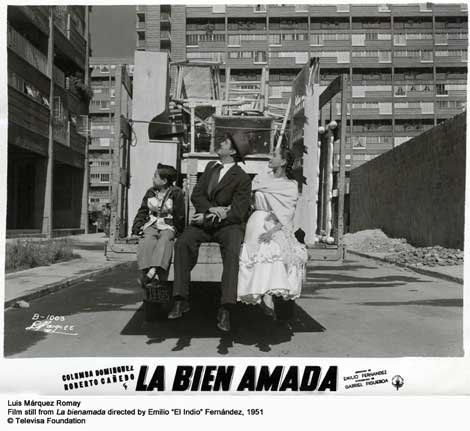

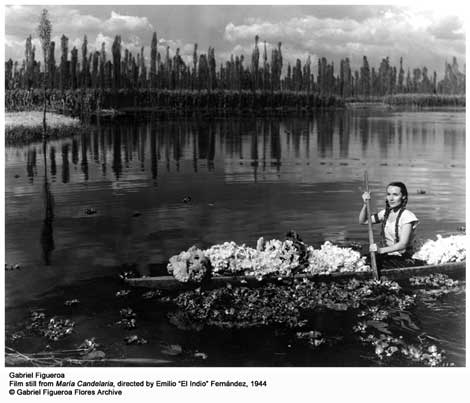

If you’re a film buff, you’ve seen his films—you just didn’t know he was the one responsible for this brilliant body of work. During the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, from the late 1930s through the 1950s, Figueroa worked alongside such great Mexican directors as Emilio Fernandez and Roberto Gavaldon. He helped create the mythic look of the new Mexico—heroic, handsome men and self-sacrificing, beautiful women against the backdrop of sere landscape and adobe houses. (Fernandez, with whom he worked on 24 films, went so far as to say, “Only one Mexico exists: The one I invented.”) Eventually Figueroa also worked with Surrealist master Luis Bunuel, doing seven of Bunuel’s 20 films made in Mexico, and also with Hollywood directors such as John Huston on The Night of the Iguana and John Ford on The Fugitive (1947).

Born in Mexico City, Figueroa grew up during the Mexican Revolution, which began as a revolt against the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, and lasted about 10 years. As a youth he studied painting and became interested in photography. He began to go on movie sets to shoot film stills, first for Revolución (1932), directed by Miguel Contreras Torres. Then he traveled to the U.S. and apprenticed with the legendary Gregg Toland, the cinematographer who would give us the epic visuals of Wuthering Heights (1939) and Citizen Kane (1941).

When Figueroa returned to Mexico, his first job as cinematographer was for Fernando de Fuentes’ Allá en el Rancho Grande (Out on the Big Ranch) (1936), a box office winner that also won him an award at the Venice Film Festival. It set the standard for future “comedia ranchera” which featured the charro (horseman/cowboy), along with doses music and light romance. Over the next half-century, he would rack up an incredible tally of credits: 235 films.

Figueroa’s began his cinema career at just the right time—by 1947, movies were Mexico’s third-largest industry, with 32,000 workers and four active studios. There were about 1500 theaters in the country at the time, with 200 in Mexico City alone. Part of this was due to government support and subsidy.

“Under the Mexican Sky” does more to convey the sheer power of the moving image than anything I’ve yet seen. The curators—Rita Gonzalez and Britt Salvesen of LACMA, and Alfonso Morales of the Televisa Foundation—aimed for visual immersion. It starts with film excerpts the moment you walk into the introductory space and then into the first major gallery. There, four screens in a row to your left project continuous montages of larger-than-life figures. These are loosely grouped by theme—the Mexican Revolution and individuals caught up in it; landscape and its vast beauty; death, through dancing Day-of-the-Dead marionettes; and women’s tremulous faces, close-up and often glistening with tears. Figueroa found great affinity with women, putting his loving camera on such actresses as Maria Felix and Dolores del Rio.

Here you can see the genius of his vision. He effectively alternated close-ups with long shots, light with shadow. He was clearly in love with velvety darks, and understood how our eye is drawn to contrast, and he emphasized chiaroscuro effects in nighttime scenes. He had plenty of opportunities to show night—men and women who worked at nightclubs, soldiers marching through evening streets, a woman trying to catch a glimpse of her lover before he departs. He was fond of unusual or extreme angles, such as a floor-level shot of shuffling shoes as couples dance in a nightclub. He also played with tempo, unafraid to show lingering shots of a man climbing to the top of a buff and looking over a fertile valley, or a man, woman and child very slowly turning their faces together.

There are also four rooms, the openings facing the other way, which show more films closer to eye level. If there’s one criticism I have of this exhibition, it’s that in this gallery the list of films is only available at the end of the clips—and not on the walls where they would have been handier references.

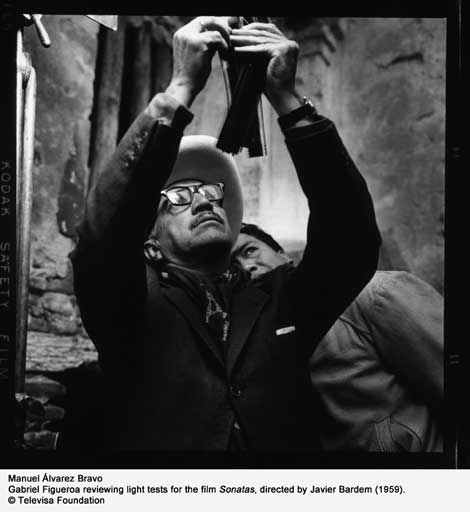

To add to the context of Figueroa as part of a resurgence of national identity are a number of drawings, prints, paintings and photographs by contemporaries such as Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, Edward Weston and Manuel Alvarez Bravo. And yes, LACMA’s own iconic Rivera painting Flower Day from 1925 is included.

In the 1960s Figueroa began working in color. These comedies and stories based on telenovelas look a bit slapdash—maybe it’s the garish fashion of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Also, he was apparently uncomfortable working with color, since it had to be processed outside Mexico, so you couldn’t see the results right away. Another problem, I think, is that color cinematography requires more overall or even lighting, and he lost the depth of shadows he was so adept at working with.

Toward the end of the exhibition, there’s a showcase and two giant posters dedicated to The Night of the Iguana, a film that had a lot of buzz and build-up from the cast and steamy story involved (adapted from a Tennessee Williams play). Elizabeth Taylor visited Burton, actress Sue Lyon was still fresh from Lolita notoriety, and so on. Working with such a cast, which included Ava Gardner and Deborah Kerr, must have been an impressive experience, but the movie shows Figueroa working his personal best. Take the moment Burton takes over the wheel of the bus, in an attempt to steer his passengers to a different hotel. While the bus careens, you see the back of his head (what ladies would have seen), then from the windshield looking in so we see his glazed eyes and the frightened women behind them, then the road ahead (what Burton would have seen), and so on. Figueroa was nominated for Best Cinematography by the Academy, but here was a man who didn’t work for awards—rather for the sheer exhilaration of making beautiful moments come to life.

Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film at LACMA, September 22, 2013–February 2, 2014

Previous Spread (l-to-r): Gabriel Figueroa reviewing light tests for the film Sonatas, directed by Javier Bardem, 1959 © Televisa Foundation. Photo by Manuel Álvarez Bravo; Light test from the film Pueblerina, directed by Emilio Fernández, 1948 © Televisa Foundation.

Above: Movie still from Maria Candelaria, directed by Emilio Fernández, 1944 © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive