Given the current political climate, one in which President Donald Trump in February withdrew Federal guidelines allowing transgender students to use restrooms matching their chosen gender, “Masculine-Feminine” offers a timely and relevant examination of gender identity and topics related to sameness and difference. Organized by curator David Famillian with artist and curator Micol Hebron (whose sculptural installation is also featured in the exhibition), the show is a surprisingly comprehensive survey of both historic and contemporary works despite the limitations of being a smaller campus gallery. The most prominent unifying element is the direct reference to the physical body as a vehicle for exploring topics related to gender identity, specifically within the context of new media and technology.

Towards the beginning of the exhibition viewers encounter four photographic prints by transgender artist Cassils: Time Lapse (Front), Time Lapse (Back), Time Lapse (Left) and Time Lapse (Right), (2011), from the series “Cuts: A Traditional Sculpture.” The sequential imagery, meant to be a reversal of Eleanor Antin’s 1972 Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, also recalls the performative, gender-bending works by artist Lynda Benglis. The use of the body and self in this type of photo-documentation is embraced by Cassils and other artists like Laura Aguilar or Catherine Opie, who identify with gay, lesbian, transgender and queer culture. Cassils pushes the boundaries of photographic portraiture; the repetition of imagery divided in a systematic, grid-like pattern, effectively denotes both separation and passage of time and narrates Cassils’ ardent determination to address masculinity and femininity as social constructs through their radical, deeply personal physical transformation.

Hiromi Ozaki (Sputniko!): Menstruation Machine, 2010, ©Hiromi Ozaki,Loan courtesy of SCAI THE BATHHOUSE INC (Tokyo), image courtesy Will Tee Yang.

Menstruation Machine (2010), by Japan-based artist Hiromi Ozaki (Sputniko!), consists of a wearable sculpture and film, to help men understand the biological experience of womanhood. The machine is intended to be strapped to the waist while pulsating electrodes induce abdominal cramps and release a red liquid. The accompanying film reflects this imagined future, one in which Takashi, a young male protagonist played by the artist, constructs and wears the machine to relate to his female friend’s experience. While the sculpture is more symbolic than functional, this installation, more so than any other artwork in the exhibition, questions perceptions of gender identity while also envisioning future possibilities through biotechnology.

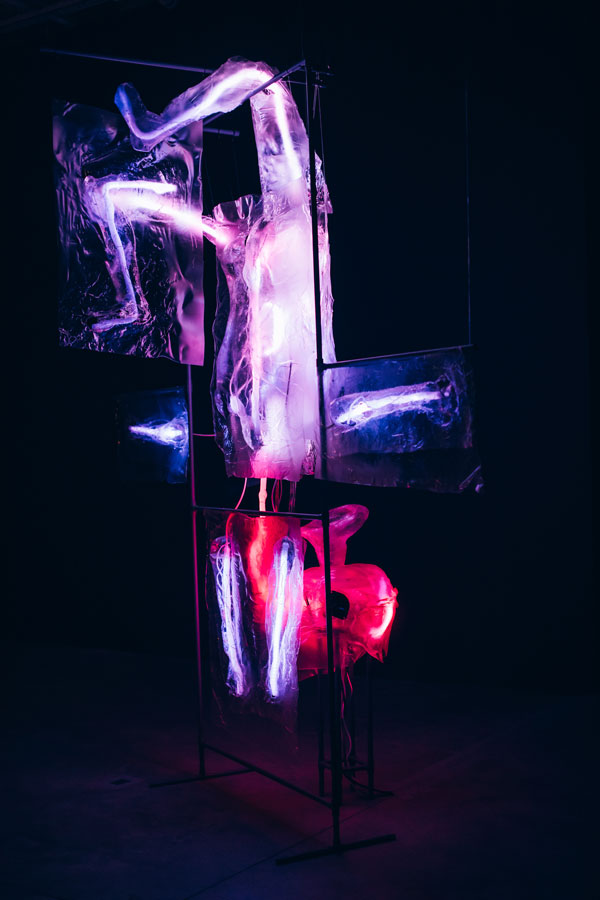

In the last half of the gallery stands Danial Nord’s Sleeper (2017), a multimedia installation with color-changing LEDs, translucent polymer forms cast from the artist’s own body, and audio recordings of voices from social media. The rectangular stacked shapes recall the figure-shaped structures of pioneer media artist Nam June Paik, but with a Brave New World kind of austerity. Nord’s dystopian self-portrait dominates the gallery space and functions as a palpable reminder of present tensions in the current sociopolitical atmosphere.

Other historic works included in the exhibition by pioneering artists Alexis Smith, Austrian-born Maria Lassnig, Lynn Hershman Leeson, and others, help contextualize the more recent contemporary artworks. Upon exiting the galleries visitors are encouraged to write responses to the prompt, “What is gender?” directly onto the gallery wall. Given the myriad of divergent responses, the quest for, as the exhibition description states, “freeing us from the masculine/feminine binary,” continues.