It takes guts to imagine former president Harry S. Truman as a strange and profligate hero, a man who played a significant role in authoring our now debased socio/political framework, a uniquely polarizing figure who is now the unlikeliest muse in the most recent video project of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley, “In the Body of the Sturgeon.” Built around that video project, the exhibition, “America Rides The Breakfast Table,” consists of photographic lightboxes, paintings, wall texts and several sculptural works that attempt to physicalize the liminal space of this fictive universe, a world depicting the final days of a submarine crew (all roles played by Mary Reid Kelley, with the exception of a cameo by Patrick Kelley) aboard a vessel in the Pacific in 1945.

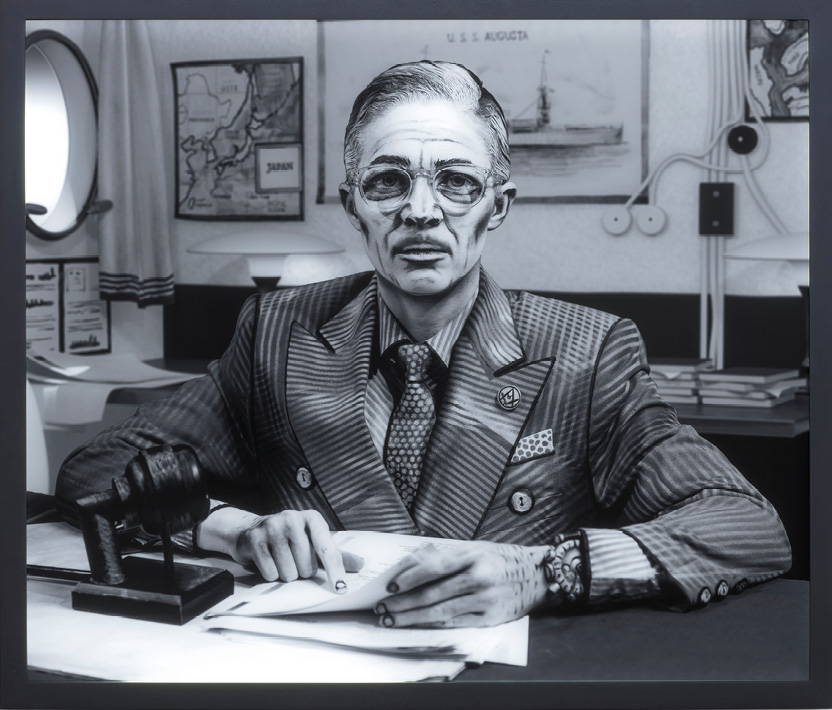

As with Mary and Patrick’s previous work, these disquieting sculptures along with Reid Kelley’s boldly graphic paintings recreate the frenzied atmosphere of the video, yet because the works are frozen within the literal space of the gallery, they are even more prescient and frightening. At the heart of this project is a deeply felt exploration of what it means to be female and invisible; in her performance (the video was performed entirely by Mary Reid Kelley, with a brief cameo by Patrick Kelley), Reid Kelley re-contextualizes yet another male centric world, repopulating it with herself playing all the male roles including Harry Truman. In one fateful image, Reid Kelley is shown facing forward as though addressing the nation, Truman’s face seemingly overlaid atop her own, only her hands betraying her true feminine nature.

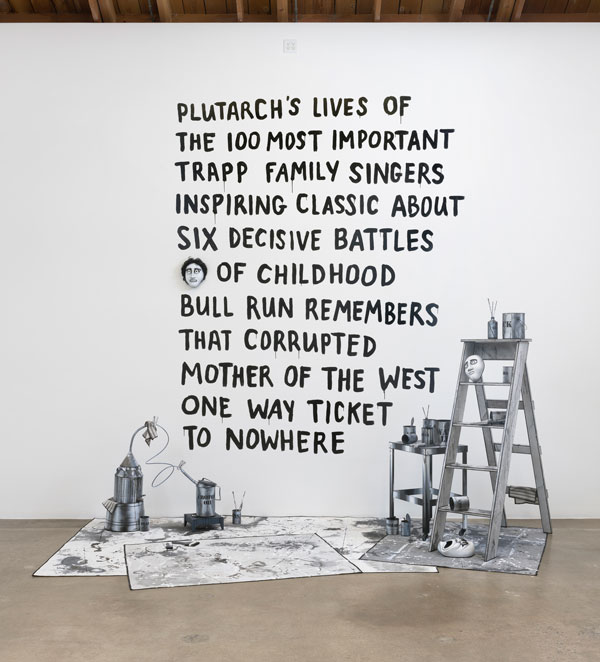

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley, Six Decisive Battles Of Childhood, courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Even the objects we see here, either in the photographs or in the sculptures themselves, appear almost as stand-ins for themselves, cardboard cut-outs of the living world wherein even a small mandolin looks as though it would crumble if actually played. The tension between reality and artifice is one of the dominant themes, yet, historically, as consumers, we more often than not prefer an artificial reality to the one we live in day to day. Yet, at the center of this highly ambitious project is a deep and abiding love of language, and an exploration as to how its bastardization can create new and unsettling meanings.

Reid Kelley’s script is a cento composed entirely of lines from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha (1855) re-composed by Reid Kelley. The result is a text that is oddly disorienting, at once violent and tender, richly discursive, yet obviously deceptive. As viewers, we want to buy into language, yet we understand all constructed narratives are deeply flawed. One detail in all of the images that stands out as truly significant, are the books we find strewn in the background of these photographs. Carson McCullers’ The Heart is A Lonely Hunter (1940) appears folded over a bunk bed frame in one image, and this one singular gesture might be said to sum up the entirety of this project, at least emotionally, as that novel is about a deaf mute whose observations form the basis of the central narrative structure of the book. How can we believe the narrator if he is indeed deaf? Can we trust his observations to be sound? “America Rides The Breakfast Table,” like McCullers’ work, poses the same difficult and largely unanswerable questions.