There’s a fabulous tabula-rasa quality present in “The Shape of Cloth.” Leveraging her experience as a masterful furniture designer, Irish-expat Mary Little presents eight existing unbleached canvas sculptures and a single site-specific piece for her exhibition at Craft in America Center. Ranging in width and depth, each sculpture stands approximately four-feet tall and comprises one material: cotton canvas. Considering the artist’s ability to harness contours and rhythms, simultaneously rigid and (seemingly) dexterous, the assumption is that wires or adhesives—something, must be complementing the fabric. However, only cotton, and skill, bring these works to fruition.

Whether premeditated intent or serendipity, Little’s work merges abstraction and figuration to politely achieve suggestion—though one might interpret the obscene. In Campbell (2015), rotund positive and negative space becomes a textured, topographic “map” of Ireland’s low glacial hill sans water or names (a visceral act of symbolic effacement); in Cooper (2017), a dentata-esque collar begs insertion but connotes castration; and in O’ Sullivan (2016), a length of discarded scroll connotes a scoliosis-afflicted spine.

This implication of violence within the sacred invites immediate categorization amidst the Christian church’s holy/violent dichotomy (e.g. any church containing images of the Stations of the Cross). Whether “The Shape of Cloth” intends to critique the banality of the “sacred” (adding to the genealogy of Marx, Feuerbach, et al.), is subject to debate. Fact is, the exhibition presents Little’s at-times violent compositions—torn, curled, altered, etc.—in a consciously tranquil environs; the exhibit walls are sky-blue. Perceive this as one may.

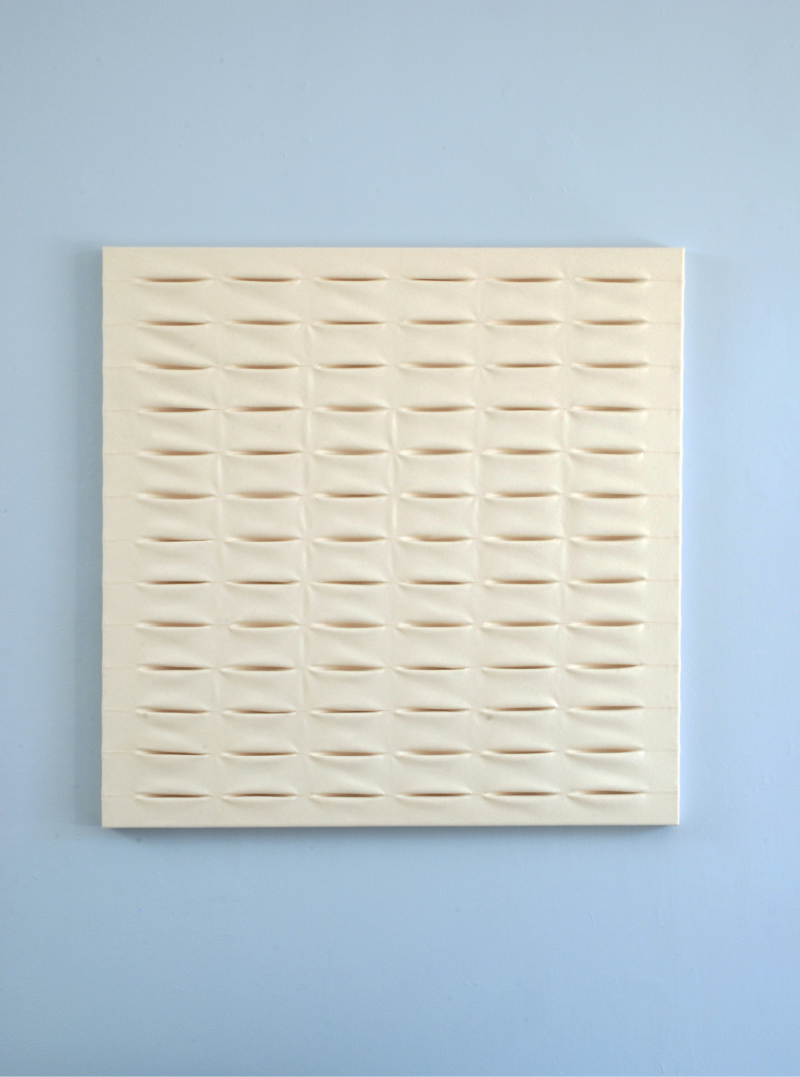

It is nomination that invites any dichotomic play between abstraction and figuration (or even between the sacred/obscene); if Little didn’t prosaically claim that Sheelaugh (2017) was inspired by the polymeric intricacy of an Aran sweater (a type of cable-knitting), the piece would earn immediate “abstract” classification. Of note, too: every piece is “named” in that vaguely Ikea-esque fashion: Marley, Bailey, Neargh, et al. This stress of individuality emerges most successfully in the aforementioned Sheelaugh. A possible interpretation is that the artist isn’t representing an object (in a way, invoking distance and thereby power over “it”), but portraying a closeup of humankind’s own strand-like composition (i.e., DNA). Little’s work is most powerful when it is uniform, repetitious and at peace with itself. Where other works dangle, seemingly “hung” and surrendered to the inevitable violence of existence, Sheelaugh attains composure by contrasting two strengths of magnification. Knowing that materiality is itself some strange, quirky essence that seems to disappear if one looks too closely, the observer is confronted by the idea of materiality itself: what is an object but that which the group “hallucinates” into shared existence? Because really, what is anything but what one’s own brain determines? And what is a brain but, at the basest, a culmination of interconnected strands traversing time?