There is something inherently contentious about an exhibition juxtaposing the work of a contemporary artist with another whose work has some place within the art-historical canon, more particularly one of the most resonant antecedents of the late 19th- and early 20th-century avant-garde. Markus Lüpertz, who has practically made a career of this sort of provocation, has engaged the work of, among others, Corot, Courbet, Picasso and Poussin.

The artist selected here for appropriation, deconstruction and more is the willfully classicizing proto-Symbolist painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (hereinafter Puvis), who exerted a profound influence on Post-Impressionist artists including Gauguin, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Bonnard, even early (e.g., “Blue” period) Picasso, and still later, various Surrealists. For this show, Lüpertz and his curatorial colleagues at Michael Werner contextualized the contemporary artist’s body of work (18 paintings variously executed between 2013 and 2022) amid 38 paintings, drawings and sketches by Puvis. This aspect of the show, which abundantly evidences Puvis’ extraordinary gifts, also serves to track his enduring influence on avant-garde art.

Art historian (and Puvis scholar) Aimée Brown Price writes in the catalog for the show, “[Puvis] was an aesthetic wolf in classicizing sheep’s clothing.” This might be a slight exaggeration, but there was no denying the lupine ferocity of his pursuit of beauty, a specifically French understanding of classicism and a sheer mastery of execution. Lüpertz might be similarly described. Generally characterized as Neo-expressionist, Lüpertz’s work has zigzagged over the years, encompassing everything from Pop to the quasi-conceptual. But what comes across most consistently is an unsettled, even distrustful, relationship with both the past (especially classicism) and the very notion of an avant-garde. In one of the very first paintings seen here, Lüpertz remakes Amor + Psyche (2020)—against an almost schematically color-field backdrop, with its chubby, black-eyed Cupid figure all but fleeing his would-be seductress, both figures modeled in slashing high-contrast strokes—into an allegory of petulant disavowal.

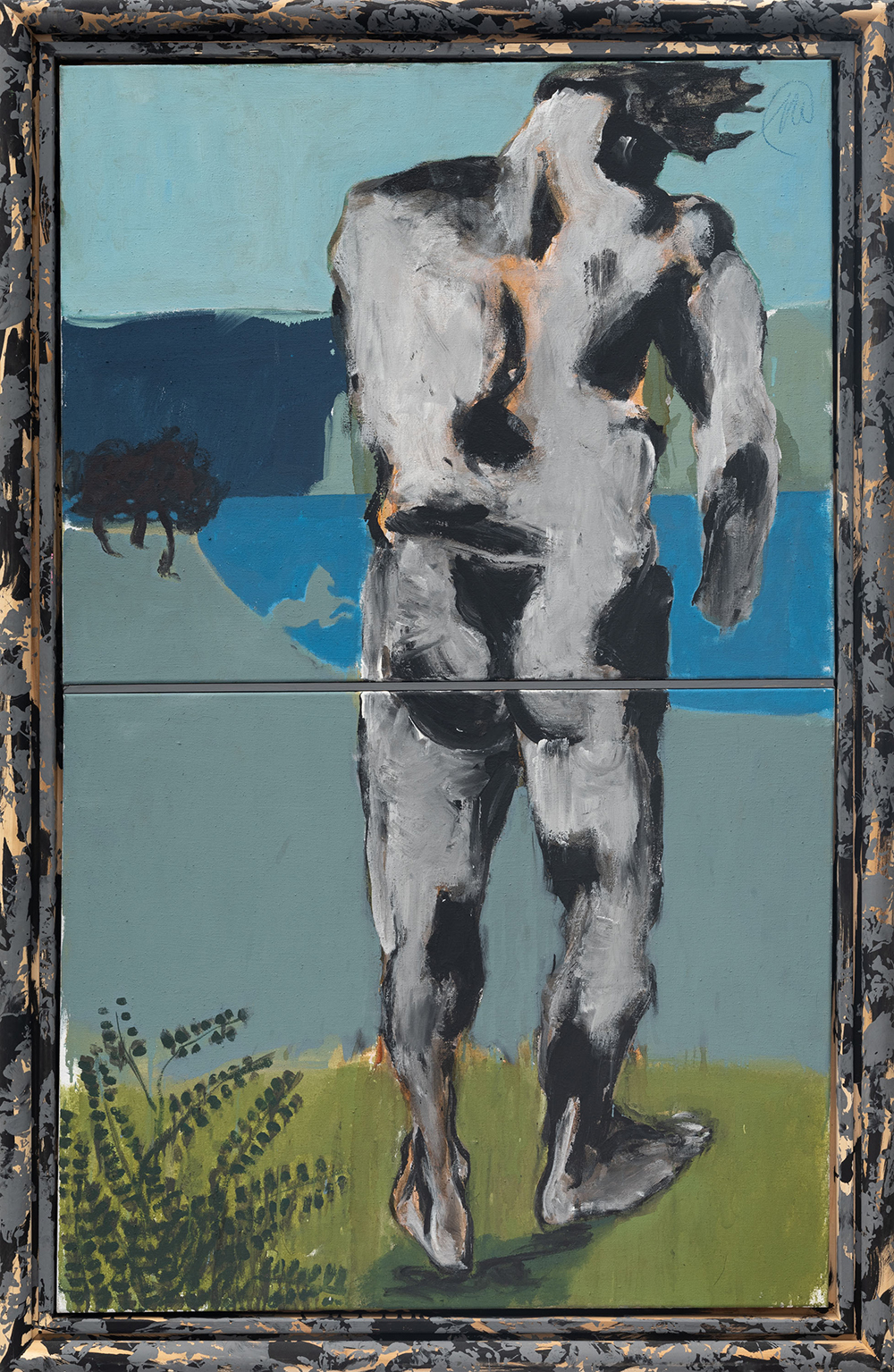

Markus Lüpertz, Orpheus, 2014. © Markus Lüpertz. Courtesy of Michael Werner.

Where Puvis meets his muse in a domain of infinite Baudelairean “correspondences,” for Lüpertz, such correspondences may be entirely illusory, or simply don’t apply. Consider the two “classical” figures that faced each other across the same gallery set against almost identical riparian or estuarial landscapes (no less “classical,” but perhaps closer to an actual German landscape familiar to Lüpertz). In both Caput Mortuum (2020) (literally “dead head,” also a purple-brown pigment) and Russian Green (2020), some portion of the setting, or the figures’ engagement with it, is suppressed, as if to suggest the “pastoral idyll” is itself an arbitrary construct.

Lüpertz’s approach is not simply to appropriate, but to isolate, to foreground, to take apart—sometimes physically: not just diptychs, but even dividing the field into multiple panels, as in the six-paneled Lido (2020), within the same frame. Here too, he draws from disparate classical sources, including Titian and Ingres, as well as Puvis. But more telling are those works in which the isolating—a kind of collage or flotation effect—happens in a single, self-contained field, as in Untitled (2016), with its uprooted and slightly unhinged “allegory.” Here, inconvenient details intrude on already displaced, defrocked “gods”: the fractured trees on the horizon, the soldiers’ crosses at the feet of a “Venus” or “Daphne.” Without overstating the contextualization of the Puvis master drawings here—e.g., a Christ with Tormenters (1858), that is almost a perfect inversion of the Daphne/Venus in the Lüpertz painting—could such an “Eden” be anything but a killing field?

Setting aside the strengths (or weaknesses) of the derailed allegories of the first gallery, the strongest works exhibited may be the paintings dominated by a solitary figure, only one of which owes a clear debt to Puvis (Narziss II [2016]—the title figure appropriated from La Fantaisie [1887], with Puvis’ own “blue hour” palette intensified to a twilight translucence). Lüpertz has a way of articulating what’s misshapen about a subject within a minimalist schema. In Orpheus (2014), a vertical diptych, the full figure viewed from the rear, head bowed and roughly modeled in Lüpertz’s aggressively tachiste slashing strokes, is pitched forward into an almost monochromatic and flattened lake-centered landscape. In both Nacht and Rotes Boot (2013—essentially the same composition), the same silhouette viewed from the waist up (also from the rear) emerges from the prow of a boat.

Plainly referenced here is Puvis’ somber, iconic Le Pauvre Pêcheur (1881), a study which was included in the show. But although Lüpertz seems to underscore a contradictory aspect within the overall body of Puvis’ work—more explicitly in Besuch von Pierre (2018), inserting his palette, soldier’s helmet and skull into the foreground—Puvis was in pursuit of something well beyond this fatalism: the overview as well as the underside, vast and transcendent.