In 2020, Mark Steven Greenfield unveiled a new body of work, “Black Madonna,” followed by “HALO” in 2022, both at the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. Gallery owner William Turner told me in an email that the “Black Madonna” show was a natural progression of Greenfield’s career of investigations into race and racial identity. “It was a sensation when we opened it in the fall of 2020,” Turner says. “It was purely coincidental, but after the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, our show became a catalyst for people discussing these issues.” Turner witnessed viewers staying nearly an hour in the gallery studying Greenfield’s intricate paintings. “We have never had a show that had that kind of depth of impact.”

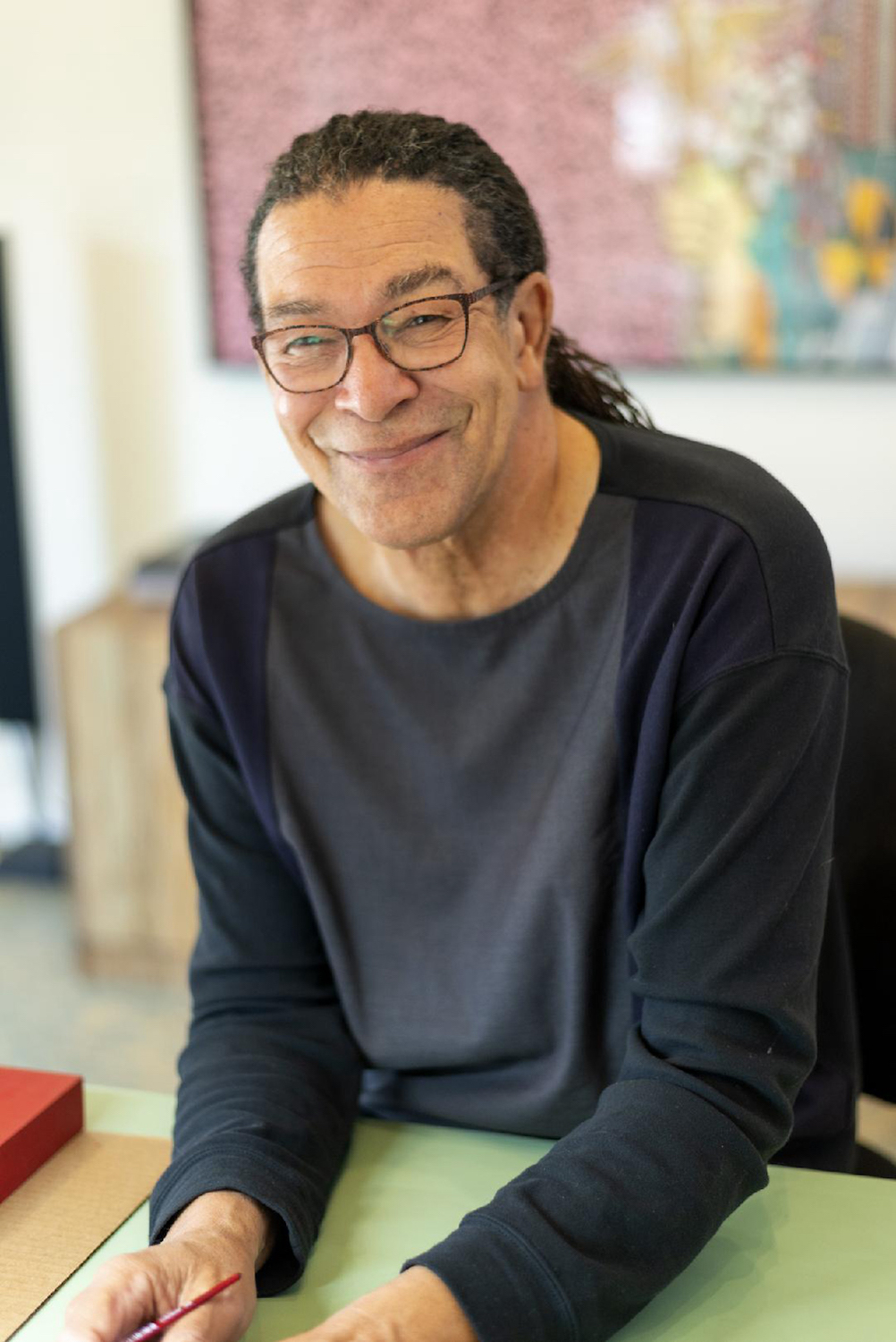

Mark Steven Greenfield Portrait, Photo Credit Tony Pinto

A native Angeleno, Greenfield is receiving well-deserved recognition. Besides being a full-time artist, he has had an

extraordinary career as a significant cultural producer in the roles of arts administrator, curator, juror and teacher in Los Angeles. Like many artists who have a hybrid career in the arts, Greenfield worked as Art Center director at the Watts Towers Arts Center and director of the Los Angeles Municipal Gallery for the Cultural Affairs Department, City of Los Angeles. His associations with over 25 cultural and service organizations are a testament to his ethos of service and support for artists and community.

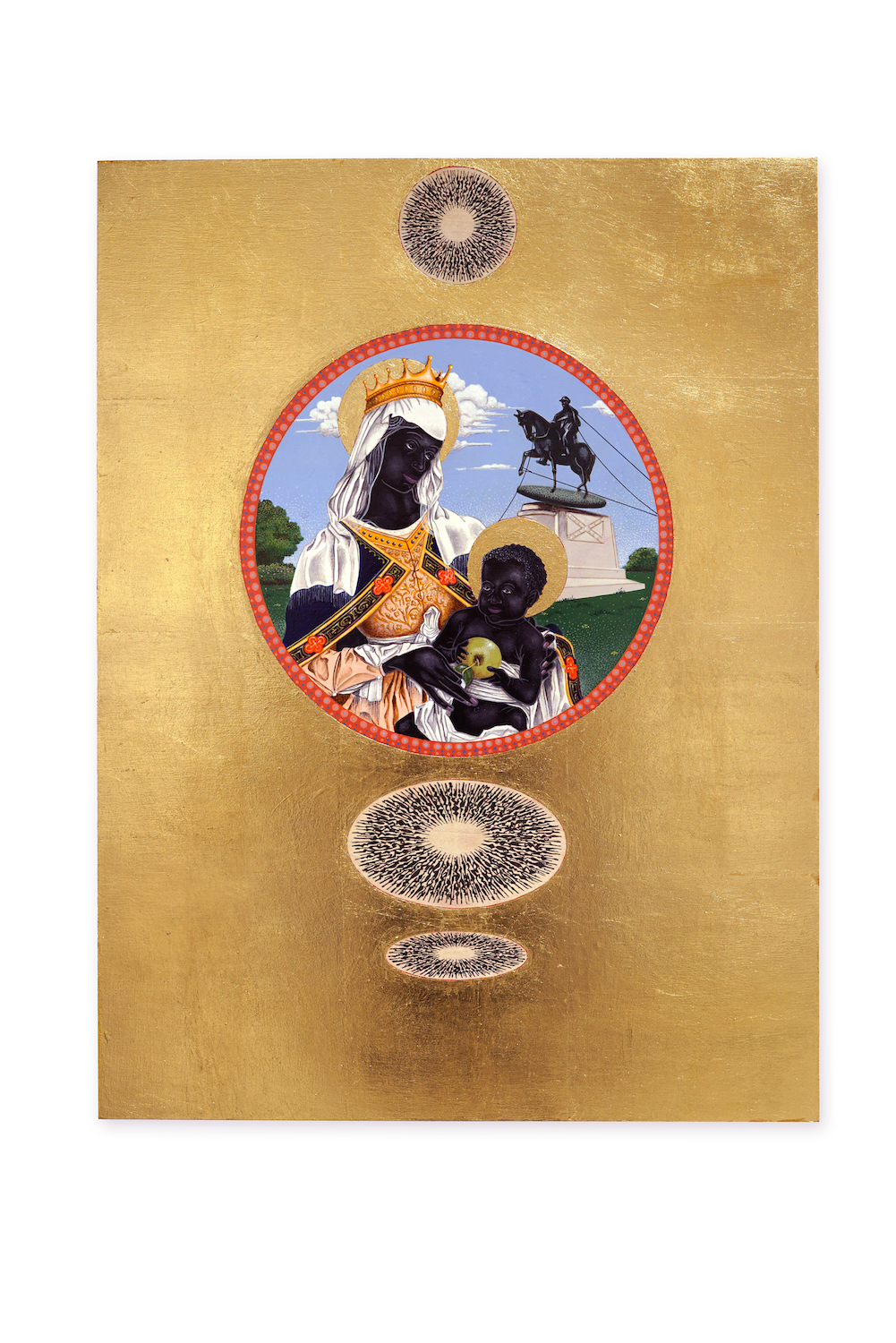

Toppling, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24” x 18”

Raised a Catholic and a long-time practitioner of meditation, Greenfield infuses his work with allusions to ritual, ceremony and spirituality. Painting images of Black and brown persons on gilded panels in a meticulous narrative, representational style, “Black Madonna” and “HALO” become symbols of empowerment and unification. When Greenfield alludes to the protective and healing purposes of traditional religious icon art, he suggests his work is also meant to offer similar forms of protection. Both his series clearly respond to the killings of African Americans by the people who are supposed to keep our communities safe. Greenfield says of his recent paintings that they “conjure up memories of the church and the reverence once paid to statues and images of saints,” but are now redirected to those who have taken up the struggle for social justice. He adds, “I made the choice of honoring those little known heroes, martyrs and personages from whose stories we might gain strength.”

Escrava Anastacia, 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24″ X 24”

Greenfield’s art practice explores and illuminates the Black experience, focusing on the effects of stereotypes on American culture. Always provocative in an unexpected way, his work stimulates a much-needed and often long-overdue dialog on issues of race. His recent summer exhibition, “HALO,” has created another conversation. While “Black Madonna” played with the idea of role reversals—revering and worshiping a Black Virgin Mary and a Black Baby Jesus as symbols of love; what if white supremacists were the victims instead of the oppressors—“HALO” evolved as a next natural progression, highlighting historical Black figures. They have been chosen from the period of the slave trade during the 1400s–1800s. He wants his subjects—often legendary in their time yet now overlooked—to be rediscoverd. Greenfield’s use of gold as a material connotes value and importance, but also currency. Most of the people depicted in the series were enslaved and treated as commodities. His figurative painting is particularly striking. Greenfield explains,“The figures are rendered in ‘ultra-black’ in keeping with their political designation and not so much for their degree of melanin. It is the element in these paintings that unifies, regardless of association, wealth, class or prestige.” Almost all of the paintings have circular glyphs, a visual device that is a through line in much of Greenfield’s work. These evoke the mantras he uses as a vehicle in his daily meditations.

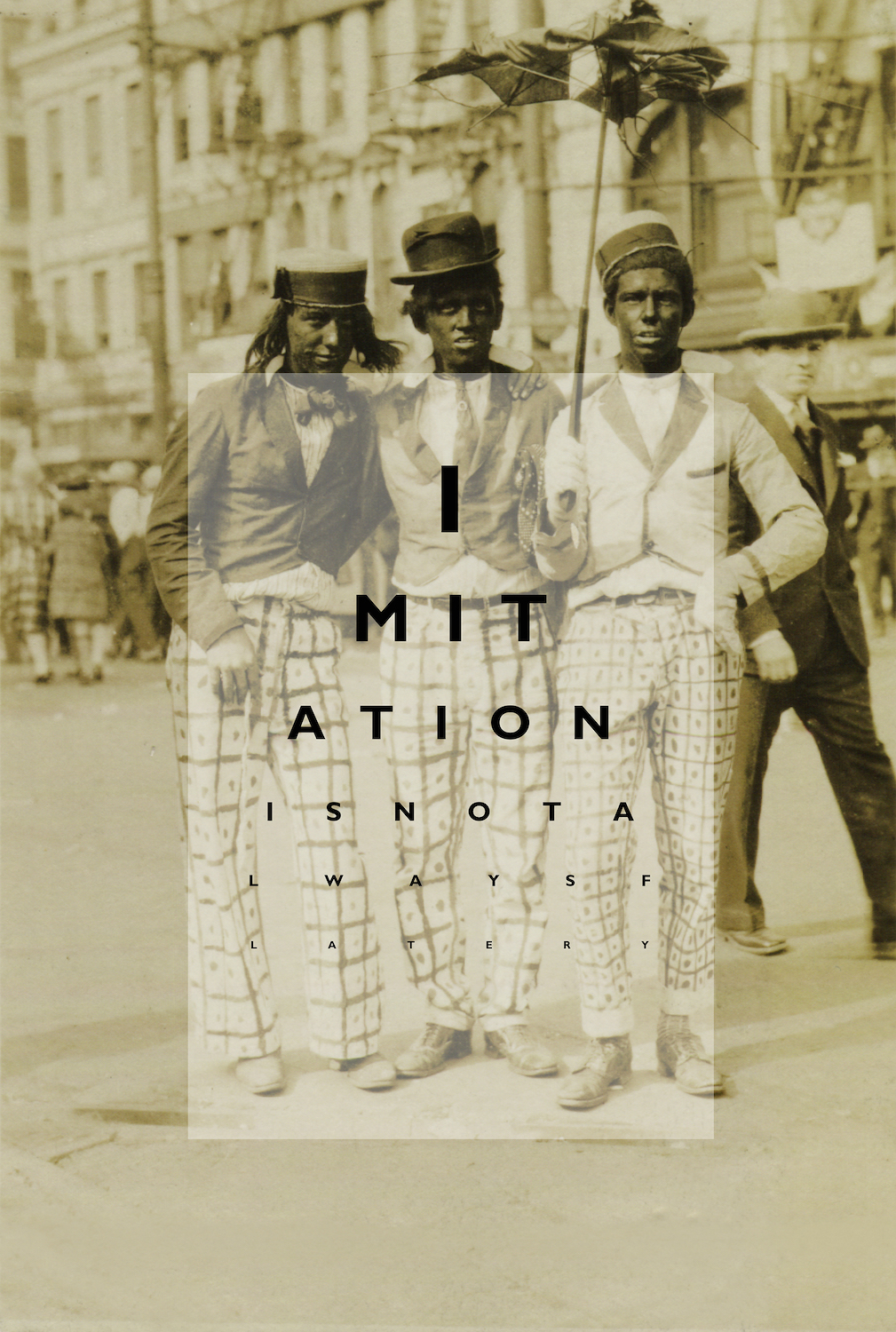

Lesson, 2002, Ink Jet Print, 37″ X 28″

In Greenfield’s work, each series has developed its own stylistic approach. For example, his 2007 exhibition “Incognegro,” at the 18th Street Arts Center, consisted of appropriated photographs. They are mainly of white people in black face, who in turn were appropriating African American culture. For this body of work, he made Iris prints and lenticular photographs. The mirror effect of lenticular photography heightened Greenfield’s intention to expose and dramatize the complexities surrounding issues of race, identity and perception. With the photos of turn-of-the-century black-face performers he superimposed a subversive message that looks like a optometrist’s office eye chart. They contain direct, challenging statements and questions about race and identity. “Incognegro” caused a stir about the use of Black stereotypes and whether they were helpful or hurtful. Mark says of this experience, “Work dealing with the indignities associated with black face has always been a messy proposition.” He believes that black-face images have haunted communities of color for a long time. His intention with this series was exorcising the demons that these images have conjured up; without that, he says, “We’ll never really be free. “Incognegro,” while problematic in 2007 for some segments of the Black community, is starting to impact whites, compelling some degree of introspection on their part. It has brought into focus the responsibilities associated with social justice and allyship. Both “Black Madonna” and “HALO” expand this conversation and engagement with a larger audience that is willing to listen and learn from the social reckoning occurring globally and locally. At a moment when many younger artists of color are gaining national attention for their identity-based work, Greenfield has always been creating conversations about racial reckoning, both as an artist and cultural producer. His unswerving commitment to self-examination and community has made him a change-maker in the best sense of the word.