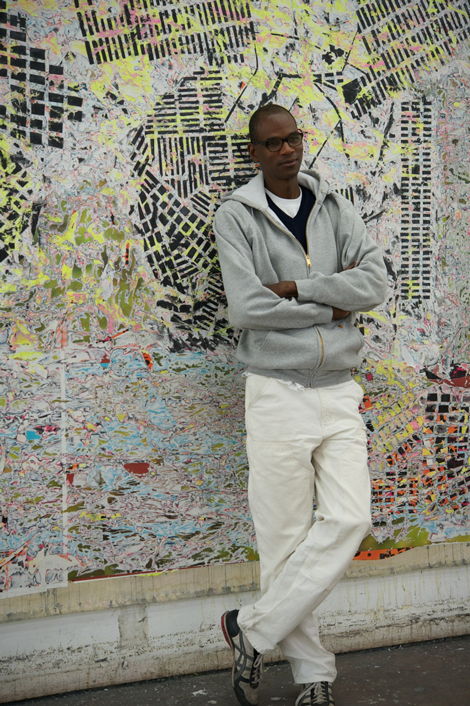

In the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, the anonymous unmarked storefront of Mark Bradford’s studio betrays nothing to passersby, but the large white security gate which rolls back to reveal a parking lot at the north east end of the property is an unusual flourish for the area. Inside, the multi-building space is organized and impeccably neat. Cocoon-like, it feels insulated from the traffic and continuous motion outside.

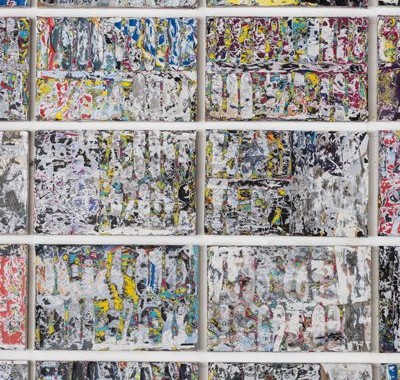

Bradford however, is inspired by the pace and the multiplicity of voices that compete for the public’s attention on the streets outside. The artist’s older works incorporate signs and posters scavenged from the surrounding neighborhoods, with the signage collaged onto his canvases. Although he says he almost exclusively purchases his paper now, he continues to use text from the “merchant posters” he encounters around the city, which advertise the services of lawyers, social services agencies and various other business ventures, reflecting the socio-economic realities of the city’s populace. His large scale canvases—which he very strategically calls paintings even though they are almost exclusively built up with layers of paper—are intensely process-oriented in a cycle of creation and destruction. He often outlines these texts on raw canvas using string or paint, then obfuscates by adding layers of paper, or obliterates by sanding, leaving only a trace when the painting is complete.

On a clear November afternoon, Bradford welcomes me into his office for the first of two studio visits. Over the course of our conversation, he meets my interest in discussing his youth living in Santa Monica and working in his mother’s hair salon in Leimert Park with a certain amount of reluctance. While he does offer some detail, most of his life story is drawn in broad strokes, and it is not until our second meeting that I come to understand, in its entirety, his practice of very clearly delimiting his biographical narrative.

Bradford credits his early experience with preparing him to navigate diverse environments. “I’ve been naturally hybrid,” he says, explaining that he has never belonged all to one community. Bradford’s mother was an orphan. “She didn’t come from a lineage of people,” he tells me. Bradford considers this early rupture one reason for his fluidity. Referring to the lack of an extended family, he says, “It was just my mother, and we”—Bradford, his mother, and his two sisters—“lived in a boarding house, which was still with people who were not living in a traditional family unit. So, I grew up in that, and I went from that to Santa Monica.”

Bradford attended CalArts, earning his BFA in 1995 and his MFA in 1997. “I thought about art-making—professional art-making— like everyone else,” he tells me, when I ask how his early development affected him as an artist. “I went to school, like everyone else, and I learned the same texts, and I learned the same structure, same rules of engagement. So I just assumed that you leave your past behind, and you begin to build a practice. So, I don’t think I was any different than anybody else, really. I didn’t bring much of my personal subjectivity into it.”

Bradford credits CalArts with opening him up. He quickly found his way into the cultural studies department and started reading writers like Homi Bhabha, Bell Hooks, and Cornell West, as well as Walter Benjamin, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. He became fascinated by the dynamism of emerging power structures, and observant of the way the world was changing. “I immediately understood that there was art theory, and that there was social anthropology. They were different departments, different people, and I also became very clear that it was a hierarchical relationship.”

At the same time, Bradford began encountering the hegemonic gaze. He found that his body was “constantly propelled forward,” he says; there was an expectation from others that his body was “supposed to be in the work.” Never before had he found his physicality “so forcefully brought to the table.” Even now, people fixate on his stature, commenting about his height, sometimes telling him, ‘if I were your size, I would…’ fill in the blank, most frequent being a reference to basketball. He quips, only half joking, “that should be the name of a piece, Well, If I were you.” A pause, then, “I’m six-foot-eight. My god,” he says, not letting writers off the hook either, “there’s very few articles that will not describe how I am.”

“So when I started to make abstract paintings, I’m sure that it was for me at the time—it was not a critique, quite yet—it was more trying to find an ideological framework that I felt would give me some space to figure it out.” Bradford was inspired by Malevich and the idea of not making images “for the people,” referring to the Russian painter’s refusal to make the Social Realist paintings encouraged by the Soviet regime. But his foray into using paint on canvas was short lived, since it seemed to him, too weighted with the history of painting, and “too heavy on the CV.”

“So I really just started working, and I just kind of came on to paper. I liked the idea that it engaged the cultural anthropology readings that I had read. It simply engaged immediately, that side, for me.”

Bradford’s interest in power structures, emergent when he was at CalArts, has continued to inform his painting, and how he conceptualizes his work. He has always been fascinated by the purity that is attributed to paint and that collage is considered lower than painting in the spectrum of media. “I was building a political framework in my head of how I wanted to engage, and what materials could push that. That is why I demand that they’re called paintings,” he says about his large scale paper-on-canvas works. “That is why people get unfurled when I call them paintings. That is why the purists stand up and say, ‘There is no paint.’” Bradford also notes the lack of African-American men and the lack of women throughout the history of painting. Finally, he points to the question of space. “Certain white men are allowed to be size-queens; they have big paintings, they can take up big spaces. It was about who was allowed to take up space, and who was allowed to not take up space. So I think for me, all this framework came out of being at CalArts and observing ideological frameworks and my relationship to them.”

While he was at CalArts, Bradford encountered the conceptual artist and professor, Charles Gaines. He took note, from a distance, thinking of Gaines as a mentor. Bradford adds that when he was growing up, while he knew many black women from the hair salon and the boarding house, he didn’t interact with many black men. But he knew from early on that he did not fit into a traditional role. What Bradford calls the narrowness of socially accepted roles for black men was not something he was comfortable with or wanted. The most prominent black male archetypes in American culture, he says, are the athlete, the rapper, the gangster, and the good pastor. Gaines was a compelling figure, “because he was a black man, who was non-traditional, and I had never been up close with that.”

Although the two artists’ modes of production are dissimilar, there is a confluence between Bradford’s thinking and Gaines’ 2008 video, Black Ghost Blues Redux, in which, Gaines explores identity constructs, examining how black men often are either culturally invisible or romanticized. In the catalog that accompanied Bradford’s survey at the Wexner Center for the Arts in 2010, Bradford is quoted as saying he has to continually “fight erasure and rigid identity constructs at the same time.” He explains, at length as we talk, the risk of being pigeonholed as an artist who tells the “real story based on race,” whenever any discourse of race or community is remotely attached to the work.

Rigid constructs can also affect the way communities see themselves or individuals within the community as much as they can affect how those outside see them. Niagara, a video Bradford made in 2006, follows a man in Bradford’s neighborhood walking down the street with an exaggerated gait. We discuss styles of walking and what they communicate. “It’s huge,” Bradford clarifies, and says it’s called “swag; he [the pedestrian] had such an identifiable brand that it made me uncomfortable to look at him. I was scared for him. He felt vulnerable and heroic at the same time. I knew that it could turn bad.”

“I understood the way in which this part of town has been historicized, politicized, romanticized,” Bradford tells me. “I love this one detail of this man that was just really breaking everything, crushing the idea of what it meant to be in South Central, with this ownership of this kind of promenade.” He continues, “You would never think of that imagery when you think of South Central. So I love to point to details that point to other conversations.”

Our conversation turns to Bradford’s new work, a sculpture that will be installed in the coming months for the opening of the Tom Bradley International Terminal at LAX. Bell Tower, which is modeled after a JumboTron screen, will be suspended over the TSA screening area of the terminal. He wanted to make something that referenced the way technology manages people, but also something atavistic. Historically the bell tower is simultaneously a site of surveillance and warning, as well as civic and cultural celebration. The maquette for the piece, which hangs from the ceiling of his studio, looks huge, yet it is only one-third scale. The interior is a spiral that creates the visual effect of a vortex.

On our second visit, Bradford suggests we drive to a new studio he has rented specifically to fabricate the panels for Bell Tower. It is in a small business park about a mile away. Inside the studio approximately six feet beyond the door is a temporary 2×6 frame wall. The opposite side which faces the interior of the studio is covered in weathered gray plywood and is angled out as if cantilevered, overhanging the floor. It looks like a giant JumboTron. Around the perimeter, stacks of plywood lean against the walls.

“We buy these boards from a guy who puts them up,” Bradford says. “They come just like this,” and he points to a weathered board with a coat of battleship-gray primer and advertising remnants. “We crow-bar off all the work.”

Two boards have matching posters of the rock band KISS, which Bradford says he’ll keep for his archive. “…this is so good,” he says under his breath, “they’re the best painting.” We line them up to view the posters in stereo.

“The paper’s really, really thick, though,” Bradford maintains, and he shows me a stack of salvaged advertisements in the corner.

Bradford discusses Bell Tower in the context of how societies use signals to organize, to move people, or to regulate behavior. “It’s the same thing at sporting events. I was at a Lakers game not too long ago,” he continues, describing how the JumboTron cued the crowd’s behavior as he watched a sea of people switch their attention from the floor to the JumboTron and back. “Watch the game, and now watch the kissing-cam. Whatever the technology is telling us to do, we do it.” Bradford draws the same comparison for airport arrival and departure screens. “You look up and it says gate number 37, and you just go to gate number 37. We’re so comfortable with being controlled,” Bradford concludes.

“The singular body is vulnerable in these spaces,” Bradford adds, “The singular body that looks up at these,” – the JumboTrons, airport displays, and TSA screening areas – “gets lost, and doesn’t know where to go.” He adds, “That’s why I wanted to use this,” and he raps his knuckle against a sheet of ply. “This has a very different relationship. It puts it down to street level,” he says, referring to the plywood’s function as construction barricades. “It all has to do with the ways in which our physicality can be so controlled.”

I ask Bradford if this is one of his reasons for resisting the pressure to make his body a subject of performance when he was at CalArts. “Absolutely! I just would not do it,” he tells me emphatically. We discuss the question of biography and his reluctance to speak about it. Bradford says that biographical narrative is expected from him, whereas, white male artists are not asked about their relationship to their community or the cultural mainstream. “That is not the case,” he says, “with the black body.” I suggest that biography can be compelling and refer to my own interest in it. He responds, “Hell, to be honest with you, its probably more damn interesting coming from you, because it’s like, you guys are the ones who don’t have to share it, so it’s more interesting coming from your side.” He laughs, adding, “Hell, we get it all the time. ‘Latina, tell it to me. Black man, tell it to me. Asian, tell it to me.’ And it’s more interesting when they don’t, and you do.”