The Marjorie Cameron exhibition arrives before one enters the gallery. It comes on the streets of West Hollywood. Banners hang from every other streetlight, advertising the MOCA show, featuring the artist’s self-portrait.

Cameron was the consummate Los Angeles insider-outsider. On the inside: married to Jack Parsons, a co-founder of JPL, an inventor of solid state rocket fuel, an occultist who ran a boarding house. His best known tenant was L. Ron Hubbard. On the inside: group sex with Bob Hope. On the inside: starred in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, was the subject of Curtis Harrington’s Wormwood Star and the defining presence in his Night Tide. On the inside: friends with Wallace Berman and part of the Semina circle. On the inside: hung around Samson de Brier’s salon on Barton Avenue.

On the outside: survived in a tiny bungalow on North Genesee near Santa Monica Boulevard. On the outside: only one solo show in her lifetime—a 1989 affair at Barnsdall Municipal Gallery. On the outside: Spencer Kansa’s 2011 biography gives the general impression that Cameron’s major struggle was profound mental illness. On the outside: died unknown and unconsidered, a footnote to the careers of men. In other word, a Muse. Another bullshit role for women.

So there, now, hangs her self-rendered visage in full reign over West Hollywood. Affixed to the light posts.

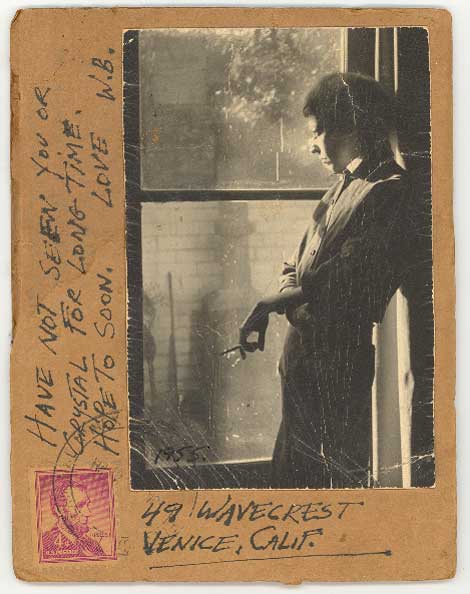

Cameron, Postcard sent by Wallace Berman to Cameron, 1955

Courtesy of the Cameron Parsons Foundation, Santa Monica.

It’s wonderful to see the artist received, to see her lauded. But it’s hard to escape the sense that it’s all too late, that the height of perversity is Cameron, almost 20 years after her death, used to celebrate the cultural splendor of a municipality that ignored her. The best artists are dead artists. All the interesting people are fêted two decades after their tongues have withered and they can no longer offer uncomfortable opinions.

Or make their own choices. Much of Cameron’s obscurity was the result of a systematic or accidental campaign to avoid the art world. Of the many works featured in Harrington’s Wormwood Star, only one remains. The others were destroyed by their creator. Burned in a fit of madness. Or an amphetamine haze. Your choice, you pick, same difference.

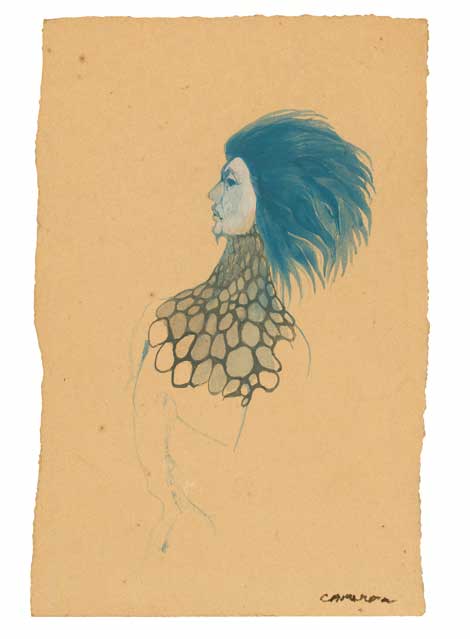

Cameron, Dark Angel, n.d.,

Courtesy of the Cameron Parsons Foundation, Santa Monica. Photo Credit: Alan Shaffer

For years, individuals with an interest in Cameron labored, literally, in the dark. Her oeuvre was unavailable, beyond assessment. One made do with scant imagery on the Internet or thumbnails reproduced in books about famous men, all overlaid with a tinge of the prurient, of the promise of Satanic Knowledge in black leather. A New York solo show in 2007, put on by the Nicole Klagsbrun gallery, was of minor drawings and gave no sense of the artist’s full output.

So a surprise comes when one enters the MOCA Pacific Design Center and sees the variety of extant work. It’s all there, from early canvases to late works. The vast majority is wonderful. Cameron had the juice, delivering a graphic genius for the line and a penchant for the fantastic. One sees a kinship with Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, every inch their equal.

The artwork reveals obvious physical traces of the artist’s life. Everything looks beat to crap, rendered on scraps of paper and pieces of cardboard, later salvaged from posthumous piles, the detritus of accumulated decades. (The Klagsbrun show also had this aspect, with the pieces looking as if they’d been pulled from a dusty floor 10 minutes before hanging.) The effect is wonderful, a reminder of the lost woman and her wild life, a unity of person and praxis.

In a world of mystical whimsy, where dreams come true, this kind of rehabilitation is where MOCA could focus its energies: On the countless forgotten and marginalized artists of California—some not even dead—not all as talented as Cameron. But surely there’s more to life than the twin polarities of CalArts and UCLA?

But everyone knows the score. One didn’t wait very long for Christopher Knight to sneer in the LA Times, employing the M-Word and praising only the most abstract of Cameron’s pieces; the boys club in full shudder, still terrified of the occult and ovaries.

There’s always hope. In the packed gallery, filled with the curious, I was the only man. You could reconcile all the conflicted feelings with an exhibition that attracted the right people. You could imagine the bright young people leaving Cameron, going out into the world, newly anointed with a previously unseen greatness. Ready to stoop, ready to conquer.

“Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman”

MOCA Pacific Design Center

Runs through January, 18 2015

Moca.org