The very model for a great photographer in the post-World War II era was Henri Cartier-Bresson, a cosmopolitan heir to a fortune who was a co-founder of the photographic cooperative Magnum and traveled the world taking photographs with his hand-held Leica camera. His is one of the best-remembered names in the history of photography. Mario Giacomelli was another photographer who rose to fame in the 20th century, making photographs with a 35-millimeter camera similar to Cartier-Bresson’s. But, that aside, he was completely unlike Cartier-Bresson because he spent his whole career photographing life in the little Italian hill town of Senigallia, where he was born.

Curator Virginia Heckert has organized a lifetime exhibition of Giacomelli’s work, on view at the Getty Museum until October 10. Despite his relative isolation in this town on the Adriatic coast, Giacomelli used photography as the kind of universal language it can be at its best. After his father had died when he was only nine years old, he left school in 1936, at age 11. Fortunately, a townsman later gave him the money to open his own printshop, with which he supported himself for the rest of his life.

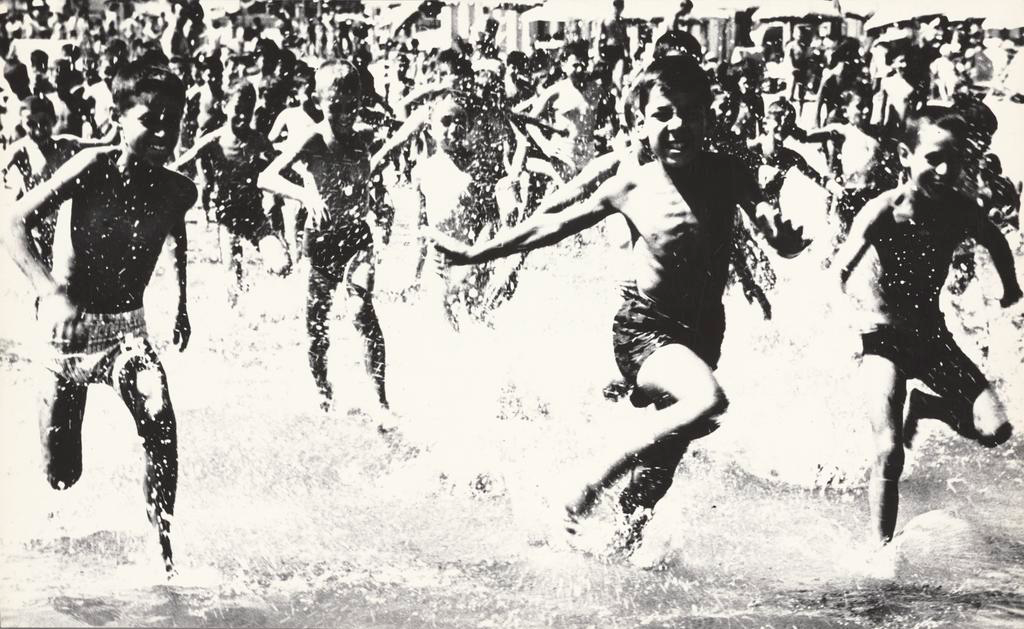

Mario Giacomelli, Children at the Sea, 1959, Courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum..png

He didn’t begin taking photographs until he was 30, in 1955, when he bought a used Kobell camera. While the fixed rituals of life in Senigallia went on as before, his life was changed once he had that camera in his hands. Nevertheless, Giacomelli’s career as a photographer was in some ways typical of the make-do solutions to problems that are characteristic of an isolated little town like Senigallia. Before he could use the second-hand Kobell camera, he had to adapt it to a Voigtländer lens. It was a unique camera that he had, as he put it, “cobbled up.”

In her wall texts for the exhibition, Heckert makes a great deal of Giacomelli’s relationship with Italy’s “postwar Neorealist film and Existentialist literature.” Did he acculturate himself in such postwar influences, or did the postwar intelligentsia just adopt him? Heckert makes a clear case for the former, despite which I’d like to believe the latter. Either way, with his raw, grainy photography he created a masterpiece appropriate to the harsh culture fixed in time that he documented.

0 Comments