Marilyn Minter’s is an art of amplification. This befits a painter and sometime photographer who came of age in New York in the 1970s; her frames of reference are feminism, the AIDS epidemic, photorealism and the Pictures Generation, equally. Minter’s work of the last quarter century synthesizes the critical but conflicted attitudes towards sex, consumption, marketing and image promulgated by the activist thinkers of the high-postmodern era. The arch observations of French deconstructionists echo, sometimes deafeningly, in Minter’s work. But the fraught attitude, now anguished, now giddy, that propels her art, exposes the urgency in that philosophy, and gives it, er, flesh. The gravity one discovers, perhaps unexpectedly, in Minter’s painting and camerawork substantiates the seeming frivolity of her subject matter, her method, and even her milieu.

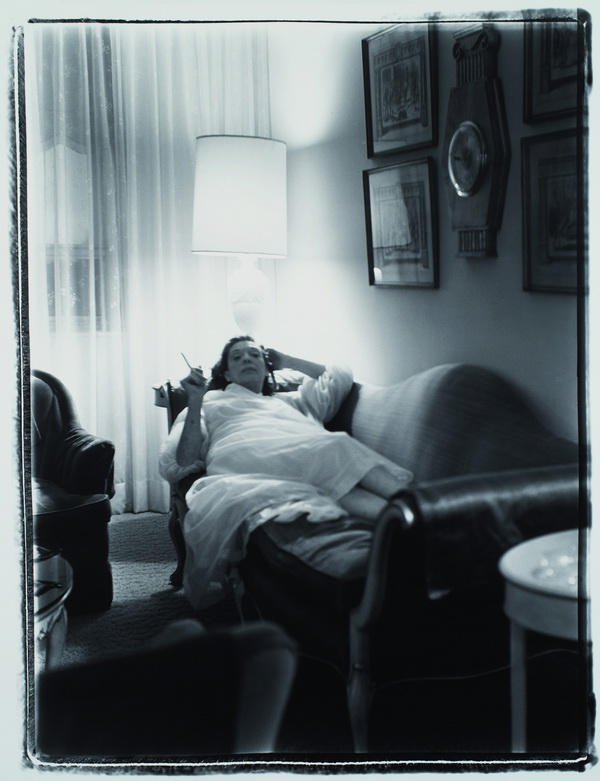

The survey, in Orange County (fittingly enough) through July 10, does not give the same weight to Minter’s work of the 1970s and ’80s as it does to her newer stuff, mostly because it can’t. She hit her stride around 1990, went big because the nature of her imagery and her message dictated doing so, and never looked back. But the pre-’90s work that is included is quite respectable and highly revealing. The show reaches back as far as 1969, to a series of photographs Minter made, while still an undergraduate, of her mother. The older lady is seen in her dimly lit Miami apartment, lounging about, putting on makeup, trying on jewelry, all in a state of disheveled half-dress. The pictures balance the weary intimacy of a daughter’s overly candid (and implicitly critical) gaze with Diane Arbus’ icy passion.

Redhead, 2015. Enamel on metal. Avenues the World School, Collection of Sherry & Douglas Oliver.

The abject claustrophobia of these photos carries over into what are presented as Minter’s earliest mature paintings, a series of hyper-realist still lifes—Vija Celmins meets Sylvia Plimack Mangold—which for the most part focus on kitchen detritus sitting on linoleum flooring. By the time she began her “Appetites” series, applying for the first time her now-signature drippy glossiness to all that skin and pulp, Minter had established that she was preoccupied with what preoccupies most women: food, fashion and sex.

Minter got into trouble for her early hetero-normative sexual images, but hindsight (as it were) now clarifies the discord built into these emphatically phallocentric porn paintings. Like Judith Bernstein and Betty Tompkins before her, Minter had to wait for the Sisterhood to catch up to her mocking appreciation of the looming Other. With that hurdle cleared, the Marilyn Minter we know and consume today could emerge, producing often immense paintings of remarkable optical complexity, paintings drenched in costumery and auto-erotica that oscillate between photo-realistic blur and glistery gesture. All the big works in the survey hold together remarkably well—a result of good curating, to be sure, but also of good composing and a knowing way with the camera after all these years. Minter’s videos are similarly deft, but they function as animated painting rather than as time-based art. She’s not a moviemaker; she’s a picture-maker. But there’s a lot of movin’ and shakin’ in those pictures.