Born in Bogotá, Colombia in 1982, María Berrío moved to the U.S. at the age of 18. Childhood recollections of exploring her family’s rural mountainside farm figure prominently in her large-scale collages depicting female figures inside vacant interiors and illusory landscapes. Appearing as symbolic daydreams of her motherland, the New York-based artist’s mythical scenes combine autobiography with ambiguous folkloric references from South America and beyond.

With an emphasis on pattern recalling that of Gustav Klimt, Berrío’s pictures are suffused with idealism tempered by mystery. Beautifully attired women with sober, dreamy miens inhabit otherworldly spaces where the patterns of their floral clothing alternately coincide and contrast with surrounding foliage, terrain and decor. Diverse motifs, including rituals of indigenous peoples of Colombia, betoken the multiculturalism of South America and the U.S.; yet these appear so general that anyone could relate to them.

Much of Berrío’s work lends visionary buoyancy to the sense of dislocation often faced by immigrants. The picture after which her Kohn Gallery exhibition was titled, A Cloud’s Roots (2018), portrays two girls leaning against the trunk of a fanciful tree modeled after an actual species, the dragon blood tree endemic to Socotra, an island off the coast of Yemen. Berrío posits that species, finely adapted for survival in a hardscrabble arid habitat, as an allegory of the figures’ potential for resiliently putting down roots in whatever harsh conditions they might encounter. The girls pose determinedly; but behind the tree is nothing but darkening firmament that seems to indicate an uncertain future.

Pieced together of painted paper and some printed material on canvas, Berrío’s works are technically collages; yet her imaginative compositions are unified so harmoniously that each canvas has the presence of a painting. Impact is added by the unexpected textures of her piebald materials: walls are suggested by wrinkled paper glued to canvas; skies are evoked by broad passages of watercolor-stained Japanese paper. A remarkable sense of depth unfolds as you approach each collage and stark expanses give way to minute areas of detail, such as a tiny framed portrait atop the nightstand in Flower Mirror Water Moon (2019). The patchwork composition of these scenes seems an apt metaphor for a transplant’s reconceived memories and restructured notions of belonging.

In fact, Berrío’s portrayed spaces are so exquisitely evocative that occasionally her relatively stiff figures fall flat in comparison. More development of her animal and human protagonists would have better served The Paradise of Others (2019), where an expressionless group of children and ibises detracts from the fascination of a strange house on stilts, denuded forest and pot of livid roses.

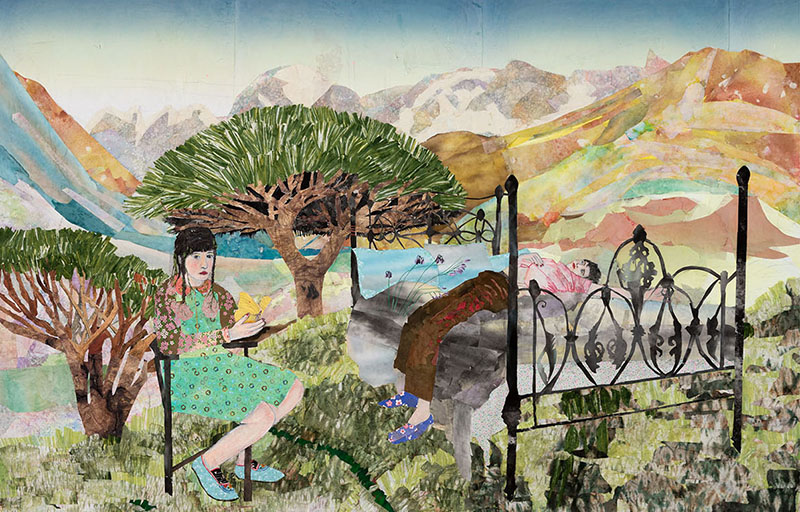

Anemochory (2019), whose title refers to seed dispersal by wind, sparkles with quiet emotion. Dragon blood trees reappear in the background of this absorbing scene portraying two figures improbably marooned in an outdoor setting. One disheveled girl is flopped width-wise on a four-poster bed as though impatiently exhausted by the interminable wait for something interesting to happen. On a nearby chair, her more neatly garbed companion sits gingerly holding a large butterfly, her sidelong gaze betraying wistfulness. The children’s nervous sense of anticipation is palpable: Like dandelion seeds, where will they go?