It’s cold. He looks even larger in his winter coat. He is a large man. Tall and broad-shouldered. In football, he might be a tight end; I’ve stood next to several players for the Bears. He would not seem out of place among such large men except that the hair on his head and beard is flecked with gray. He has just arrived at his studio—a swift bike ride from Soldier Field (yes, Chicagoans ride their bikes in winter, even in weather this cold)—and hasn’t even taken off his coat.

The Bears’ season was over a long time ago, but the season of Kerry James Marshall—from its home opener at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art to its blowout performance at New York City’s Met Breuer, to the eagerly anticipated matchup at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles—has been an unqualified success. Yet the schedule has been exhausting, and the long, successful season has taken him away from the studio. Marshall seems delighted with the weather, though. He was a Californian in his youth but has shed that skin; after enduring two-dozen Chicago winters he is made of sterner stuff. “It actually warmed up today,” he says. “Yesterday was really cold, but you know what it’s like.” As a Chicagoan for 30 years, I do. He continues, “19 degrees is like a heat wave because it was nine below zero the other night. Now it’s actually going to be in the mid-30s for the rest of the week.” Still, I’m glad this is a video chat.

Today is a studio day. Marshall and I are going to talk about painting. Not the painting that most of the recent articles—and there have been many—have focused upon, not about the refusal to paint any more white people. That is by now too easy a journalistic hook and it doesn’t delve into the complexity of his motivation and means. We are talking about the artist in the studio and the research, physical labor, experimentation, failure and invention that takes place there. “In a way, the studio’s a kind of refuge,” Marshall tells me, “It’s the one place where you have a certain amount of control over whether people can get at you or not. I go into the studio every single day. If I’m in Chicago, I’m in there. After taking care of some of the mundane everyday things you have to take care of, you take care of your stuff at home. And then I get to the studio; and for the most part, once I’m in there, then it really is like a sanctuary. I can do any of 100 things that I might want to do. The less contact I have with people while I’m in there, the better.”

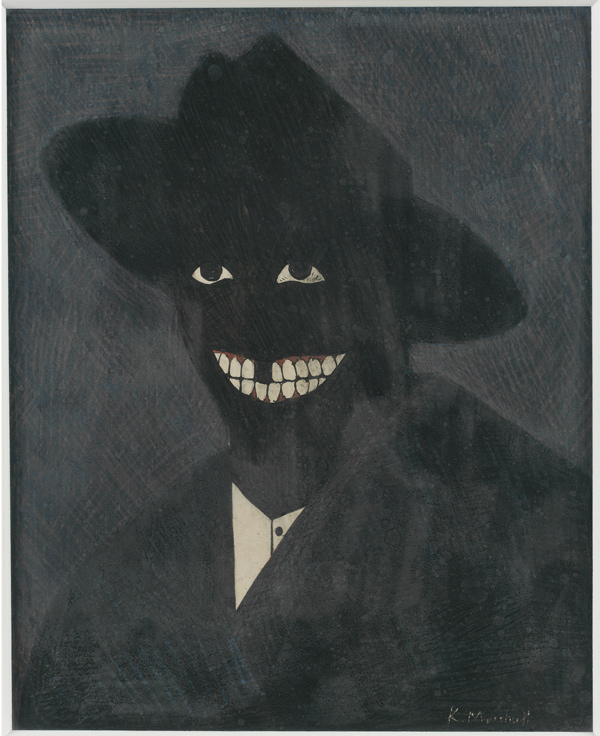

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980, egg

tempera on paper, 8 x 6.5 in., Steven and Deborah Lebowitz, photo by Matthew Fried, © MCA Chicago

Marshall’s studio is in Bronzeville, a section of Chicago’s Black Belt, a region of the city that has since the Nixon administration been home to a nearly undiluted concentration of black people. There are pockets of whiteness though: The Illinois Institute of Technology, home of Mies van der Rohe; and the University of Chicago, home of Leopold & Loeb. According to Steve Bogira of the Chicago Reader, “This African-American subdivision of Chicago includes 18 contiguous community areas, each with black populations above 90 percent, most of them well above that.” The blackness of Chicago’s Black Belt would seem impenetrable. It has, however, been nibbled at its edges. The University of Illinois-Chicago, where Marshall was a professor until seven years ago, has enveloped its surroundings including the notable Maxwell Street area, refuge for Eastern European Jews and Dixie-fleeing Bluesmen—it produced Benny Goodman and Jack Ruby. The South Loop, the neighborhood of Marshall’s old studio, featured light industry and SRO hotels. It now has macrobiotic brew pubs, sushi bars and million-dollar condominiums. Marshall’s new, purpose-built studio is now more than 20 blocks south of this relentless creep.

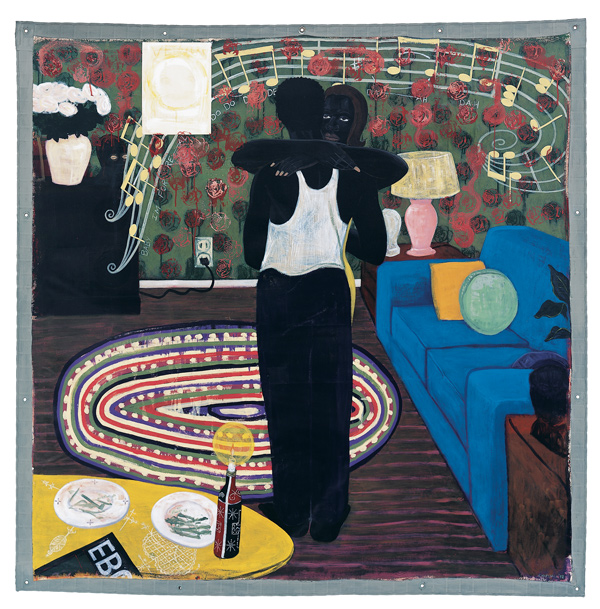

Like these neighborhoods, the population of Marshall’s paintings has been resolutely black. Yet if one considers the complexion of all the people in the paintings of Fairfield Porter it hardly bears mentioning. We are talking mainly about form now, not content. How though, I ask, does one go about the representation of figures that, pictorially, have both absence and presence, in both form and content, and how does the form engender the content? Marshall explains, “I tried to figure out how much of a suggestion of volume you could get out of a thing that was essentially flat without any modeling in it that required you to do a light and dark value scale. I was trying to preserve an essential flatness in the images, and by using a variety of textured marks while I was making the painting, try to figure out if there was a way I could suggest there was volume in the thing. I worked that until I felt like I reached the limit of where I started to think I needed more definition—because the silhouettes by themselves just never quite got to the place where I wanted the image, the way I wanted the image to resonate.”

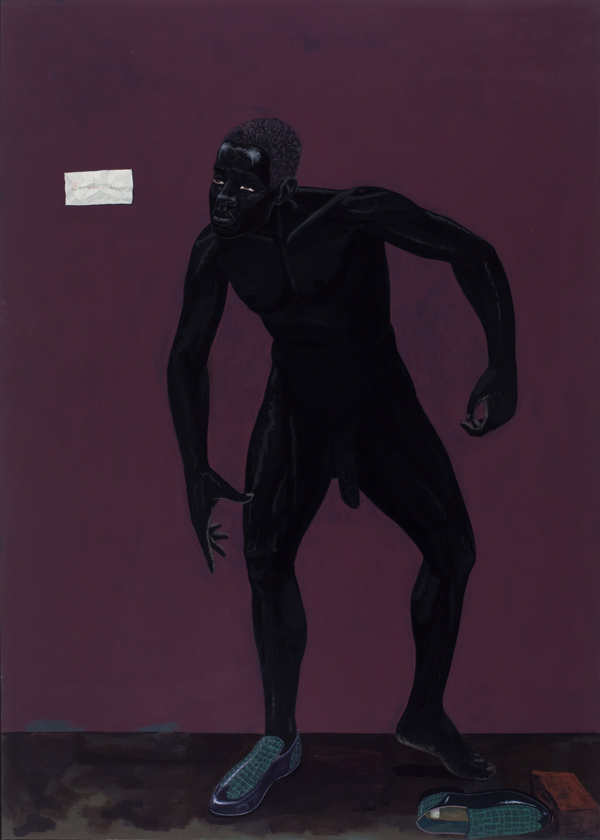

Kerry James Marshall, Frankenstein, 2009, Acrylic on pvc, 85 x 61 inches, ©Kerry James Marshall, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Marshall micromanages the tension between hard-edged shape and illusory volume: “That’s almost the way I started out, trying to do a simultaneity where you have simultaneous presence and absence, but with an emphatic presence. This has to do with lighting. I started trying to figure out a way to not compromise the fundamental blackness of the figure but create enough density and volume so that the thing seems solid as opposed to simply a kind of cut-out. By really exploiting what you could get from the already available three different colors of black, from the Mars black, which is iron oxide, to bone black, which they call ivory black, to a carbon black. They look the same in the jar basically, but they’re really different from each other, especially when you stack them on top. Then I started further modifying those by adding a cobalt blue into the carbon black and then adding a yellow ochre and then adding alizarin turquoise, so that gave me six or seven different value and chromatic changes that I could work with.”

Ambivalent flatness creates much of the visual tension in his work. While the subtleties of his blacks can make a Barnett Newman seem garish, his placement of very warm colors in the background often forces his figures aggressively toward the picture plane, requiring the viewer to feel equally observed.

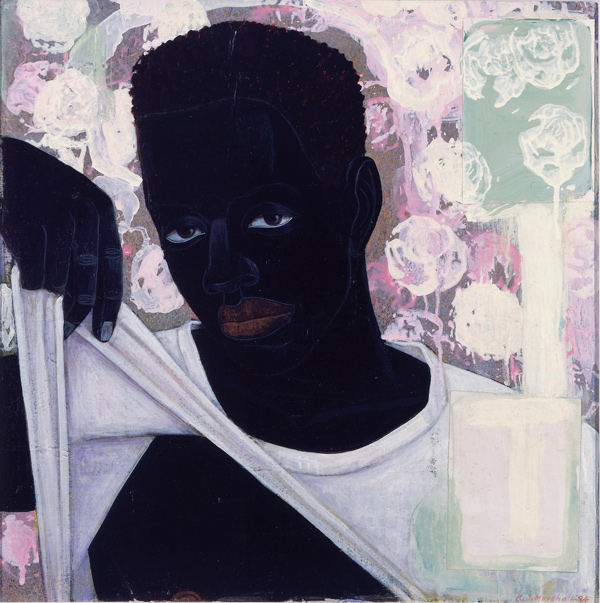

Kerry James Marshall, Supermodel, 1994, acrylic and mixed media on canvas on board, 25 x 25 inches, ©Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Two images, painted 15 years apart, vividly illustrate the stylistic change in Marshall’s approach to rendering portraits as dexterously black as the pearlescent dermatological surrealism of Ingres. Supermodel (1994) and Frankenstein (2009) both possess a Kool-Moe-Dee-How-You-Like-Me-Now brazenness, but the former is linearly defined, pressed against the window, framed in high contrast by his funereal nimbus. The latter, however, grippingly modeled as if carved from obsidian, maintains a spatial détente. He doesn’t expose his wound, Christ-like, as does Supermodel; Frankenstein, in all his nakedness, is not standoffish but indifferent because he has no fucks left to give. Yet these figures, now blacker, often glossier, exist and perform within a defined picture box. In this way Marshall becomes a director and set designer, deciding what goes in the scene and what remains offstage. Those figures must also be costumed.

“I [was] building on those [Garden Project] paintings almost like…doing a collage, but once I started working on the comic strip project [Rythm Mastr], a whole series of challenges started to present themselves that made it really hard to do. I needed to find solutions to that, and where I found the solution was actually something I had experienced while doing production design for [the 1991 independent film] Daughters of the Dust.”

Marshall struggled at first to do that comic strip, but soon realized that the problem was being unsure of how to place these various objects and characters in a manipulated yet believable space. Studying set design and perspective drawing for theater taught him the formulas. “You have to have locations, scenery, interiors that are dressed and decorated,” he tells me. “And then you have to have costumes for your characters.” His initial searches through photographic sources were inadequate, so he turned to creating the costumes himself.

At the time Marshall had a studio assistant who helped him make the tiny costumes, but the process became so elaborate she went back to college to study fashion design. After completing her degree, he turned over all of the costume design to her. He discovered there are patterns for those tiny doll clothes.

“I started using 12-inch action figures as mannequins. Then I started taking things that weren’t meant to be clothes and making them into clothes for these action-figure mannequins. When you see the figures wearing sweaters, a lot of those sweaters, in the beginning, started out as socks.” The artist learned from another artist: “Tintoretto used to set up stage settings with little wax figurines and use those as a compositional tool to develop his paintings. He would light them; that’s how he got that dramatic lighting he used with candles through a small-scale model set with wax figurines draped with cloth.”

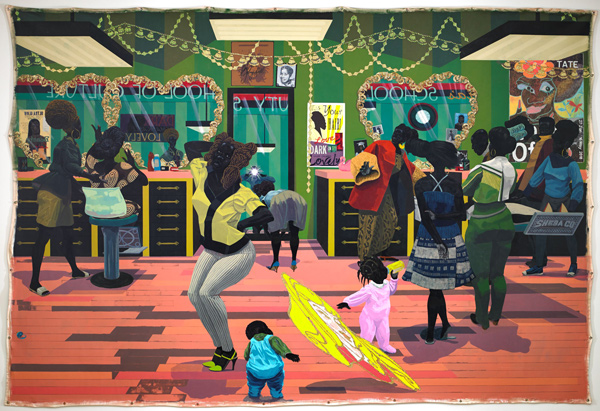

Kerry James Marshall, Vignette, 2003,acrylic on fiberglass in artist’s frame, 72 x 108 in., Defares Collection, photo courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London.

This attention to detail, this mise-en-scène deftness is particularly visible in the “Vignettes,” 2003–07 series where in five paintings a man joyously lifts and twirls a woman. The action is a 360-degree sequence, but the setting is different in each of the five images. It is as if one is witnessing the climactic scene in five different productions of the same musical. The lovers are bordered by the word “LOVE” in outsized letters and the artist’s florid signature. These subliminal prompts suggest 19th-century illustrators denoting 18th-century paintings referencing early cinematic melodramas. These repurposed motifs—still carrying their birthmarks—visually connect these tableaux to the revered canon in not simply an art-historical sense but in an artist-to-artist-how-did-you-devise-this-solution sense. “If you accept that the canon has any value at all,” Marshall elaborates, “that the baseline foundation of the whole idea of progress and development and mastery in our history, that upends our relationship to the narrative and to the museums and things like that… That always appealed to me—being able to deploy a classical technique for contemporary purposes, perfectly.”

Kerry James Marshall, Slow Dance, 1992-93, ©2015 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago.

Although he stopped teaching years ago he continues to be generous to artists seeking advice. “I still talk to a lot of people. As far as going forward, I think if I have any influence on anybody’s perception on what they want to do as an artist, I think it’s to reinforce the idea that you can be more in control than you think you can be. If you want to reach a certain level or certain place, you shouldn’t think that being programmatic is a problem—that being programmatic is a limitation. Being programmatic is just the strategy that will help you be clearer about what you think your objectives are and whether or not you get there.

“I never miss a chance to say to anybody who feels like they’re not sure if they’re being understood or insufficiently recognized: If you pick clear objectives, go for those one at a time. When you get to one place then that will tell you whether you should zig left or zag right. It’s clearer than people think it is, I believe. As human beings, we don’t really do anything that’s really incomprehensible to other human beings because we’re operating within cultures that have history and precedent.” Marshall seems really concerned with your success in your lifetime.

Kerry James Marshall, Many Mansions, 1994, acrylic on paper mounted on canvas, 114 x135 in., The Art Institute of Chicago, Max V. Kohnstamm Fund, photography ˝The Art Institute of Chicago”

Years ago, he had his first retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. He felt he wasn’t ready, that the body of work was not yet deep enough, so he used the opportunity to experiment with his work—sculpture, photography, installation—and he invited other artists to participate as well. He was fully hands-on in the planning and installation. For this current exhibition, “Mastry,” this coast-to-coast survey, his participation in the planning and curating was minimal. On this occasion, he submitted to being curated: apotheosis complete.

Yet there are two developments that belie this apparent anointing; The Image of the Black in Western Art and the Chicago Cubs. The Image of the Black in Western Art is a 50-year project of Reconquista against erasure. Its 10 weighty volumes are not a secret. They are, after all, published by Harvard University Press—no small imprint. The Chicago Cubs have now, after a 108-year period of futility, won the World Series. The first is a reckoning. A recognition of something we knew but ignored because, let’s face it, we considered it of tertiary value. The second is merely the end of a statistical aberration. Yet we cleave to our prejudices, vile and tender, until they become as undeniable as physics.

Kerry James Marshall has been here all the time, busy in his studio all along.

“Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” is on view at MOCA Grand Avenue in Los Angeles March 12–July 3; moca.org.