Having followed Gabriel Kahane’s songwriting career for some time, I was primed for a terrific show this past Saturday evening at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse. Kahane has the dual gift of an innate musical talent and extraordinary musicianship wedded to a peerless gift for story and narrative. He’s the kind of songwriter completely unabashed about showing his influences, both songwriting or purely musical and literary, because his own voice is so strikingly original and effortlessly dominant. Just in case I might have forgotten, Bill Raden’s L.A. Weekly piece reminded me that Kahane’s staged presentation of The Ambassador, his album of L.A.-inspired songs released last summer, might be a must. (The Los Angeles Times followed with a feature of its own the following day.

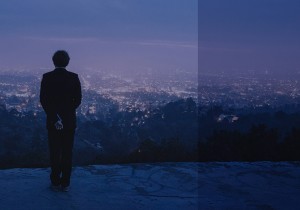

Hollywood looms large over Kahane’s vision—from film noir to disaster movies to sci-fi, to, still more specifically (directly quoting here), “action movies of the 1980s.” Even literary (e.g., Chandler) and architectural references (iconic monuments of mid-century domestic architecture doubling as film locations) are filtered through a motion picture lens. But there was a performative quality to this song cycle long before Kahane ever actually performed (as far as I’m aware) any of them publicly—something of the troubadour’s loosely connected narrative-in-song of a pilgrimage; or a passion play strung between eccentrically placed stations. The Ambassador is something of a throwback to a time when songwriters and musicians consciously shaped collections of songs into albums that, even without a strict conceptual frame, cohered into a unified vision. (Unsurprisingly, these include some of the songwriters whose influence is most apparent.)

Hollywood looms large over Kahane’s vision—from film noir to disaster movies to sci-fi, to, still more specifically (directly quoting here), “action movies of the 1980s.” Even literary (e.g., Chandler) and architectural references (iconic monuments of mid-century domestic architecture doubling as film locations) are filtered through a motion picture lens. But there was a performative quality to this song cycle long before Kahane ever actually performed (as far as I’m aware) any of them publicly—something of the troubadour’s loosely connected narrative-in-song of a pilgrimage; or a passion play strung between eccentrically placed stations. The Ambassador is something of a throwback to a time when songwriters and musicians consciously shaped collections of songs into albums that, even without a strict conceptual frame, cohered into a unified vision. (Unsurprisingly, these include some of the songwriters whose influence is most apparent.)

What this brilliantly conceived and executed staging by John Tiffany and his fabulous production team captured was the magic lantern quality of film images and the movies themselves (as originally produced for the darkened ‘magic box’ of the movie house) in their analogue relation to the space of personal memory, dreams and the intersections of both in the real world of events played out in public and private spaces. But this is above all a personal journey—a mapping of that interior space onto physical and historical space. It begins in the smallest space—for all Kahane knows, it could be the womb—the backseat of an automobile, an elevator car. Behind all the dread and foreboding is a vague suspicion that it’s all foreordained—bred in the bone—as narrated in one song (“Empire Liquor Mart”) by the lovely bones of one of the youngest victims of the 1992 post-Rodney King riots. It’s a vision that’s both anarchic and almost claustrophobic. You don’t necessarily need a native voice to articulate this dread (e.g., Joan Didion). We brought it with us—whether we were traveling by prairie schooner or jet plane, Santa Fe Railway or Route 66.

The challenge for the stage production is in connecting those finely observed fragments of micro-memory (e.g., a mother’s “earrings” and father’s “sunburn,” the “old man” in a “Westin Bonaventure Hotel” elevator) into the larger journey limned by the song cycle—to the places where memory goes from ‘faded to forgotten.’ (I thought it just slightly ironic that Kahane should see the end here, under a ‘sea splitting the pilasters,’ when New York’s Grand Central is no less likely to find itself submerged; a no less ironic but fitting coincidence that Kahane should set this envoi in “Union Station,” where scarcely more than a year ago, The Industry staged the Christopher Cerrone opera, Invisible Cities.) But I also heard the song cycle as a mission of rescue and retrieval—“The Ambassador” referring not only to the late Ambassador Hotel, but a sort of Jamesian anti-hero, desperate to retrieve not necessarily a lost ‘self,’ but an idealized vision of life’s possibilities.

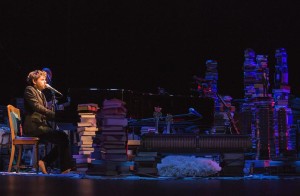

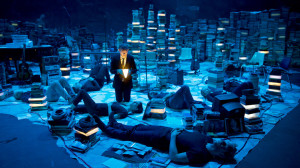

With a view toward keeping those small moments alive, while surveying the broad desert-to-sea basin floor range of the journey, Kahane and Tiffany trace the elusive connections with a spare but richly atmospheric setting, both in terms of the staging (props, placement, lighting) and the musical ensemble (eight musicians, including Kahane, beautifully deployed). At one point, the strings (violin, viola and cello) continued bowing while rolling on their backs in a slightly fetal curl. Alex Sopp did triple (or quadruple?) duty in a long, very geometrically cut skirt and cropped top, providing sustained back-up on keyboards, interrupted only by her own vocalizing, flute solos, and choreographed movement amongst props and fellow players. Stacks of books, CDs, old VHS cassette tapes, and the odd lightbox made a city of high-rise detritus, alternately flickering in the shadows and set aflame on cue by Christine Jones’ excellent lighting, and further enhanced and enriched by audio and visuals from obsolete technology: reel-to-reel tape deck, photo slide transparency carousel, etc. These provided a kind of connective tissue to the production (though the architectural model—of the (I think) Neutra Lovell “Health” House—was a bit of a stretch). It was wonderful to hear Bogart in a bit from The Big Sleep; a voice I think was James Ellroy’s reading from either one of his own novels (Perfidia?) or Mike Davis’s City of Quartz, I can’t be sure—which may be one more proof of Kahane’s larger point.

I thought the ending was magical, with its serene recessional of the musicians (a kind of ‘farewell’ elegy) punctuated by Kahane’s epiphanal opening of a light ‘book.’ It takes a certain willfulness to ‘drown history,’ suspend motion, confront the “anguish, anger and aspirations,” and take the long view through the sunlit haze bathing L.A.’s bleak basin—and perhaps a certain faith to, as Didion’s Maria Wyeth put it, “go on playing.” Our ‘Manifest Destiny’ is fueled by our manifest desperation. But the song, the story, the journey create their own reward. What isn’t lost ‘like tears in rain’ (Kahane nods to the power of that transfigured cinematic moment) is the power of Kahane’s musical voice—richly textured, rhythmically and harmonically inventive—and lyrical gift—both impossible to categorize; and a vision to equal that scope.

I thought the ending was magical, with its serene recessional of the musicians (a kind of ‘farewell’ elegy) punctuated by Kahane’s epiphanal opening of a light ‘book.’ It takes a certain willfulness to ‘drown history,’ suspend motion, confront the “anguish, anger and aspirations,” and take the long view through the sunlit haze bathing L.A.’s bleak basin—and perhaps a certain faith to, as Didion’s Maria Wyeth put it, “go on playing.” Our ‘Manifest Destiny’ is fueled by our manifest desperation. But the song, the story, the journey create their own reward. What isn’t lost ‘like tears in rain’ (Kahane nods to the power of that transfigured cinematic moment) is the power of Kahane’s musical voice—richly textured, rhythmically and harmonically inventive—and lyrical gift—both impossible to categorize; and a vision to equal that scope.