Upon entering the gallery it is hard not to do a double-take. Seated, hunched over on the railing that parallels the entrance is a life-sized figure, the artist’s doppelganger. This crocheted replica dressed in his signature clothing— a blue t-shirt, black Levi’s jeans, and Vans shoes— gazes across the threshold at a projected video Prende la Luz Que Tengo Miedo, (all works 2019). Throughout the ten minute loop, a woman (the artist’s wife) slowly shaves his head and face with an electric razor while Luis Flores stares intently into the camera. He goes from having a full head of hair and a long beard to being clean-shaven and bald. At the end of the sequence, he sheds tears. As his visual appearance drastically changes, Flores exposes his vulnerability, perhaps letting go of a certain image of himself (and his crocheted representation). This moment permeates the exhibition.

Flores’ life-size figures are always dressed in store-bought clothes, yet have crocheted hands, arms, and faces. While in previous bodies of work the sculptures were posed as wrestlers and showed off their masculinity in contrast to their material, in this new body of work, they are also lovingly engaged with family. Conscious of the connotations associated with crocheting as women’s work, Flores subverts this stereotype using yarn as a material for sculptures. For this exhibition, Flores has created soft, life-sized, doll-like forms that demonstrate their love as well as their strength. In Pull Up, the figure is suspended off the floor, hanging from a high door jam in the midst of a pull-up. While the persona in Pull Up is showing off, the sentiment expressed in Papa’s Baby Bear is one of compassion and love. Flores is a new father and in Papa’s Baby Bear he depicts his child, who is actually named Bear, like a crocheted teddy bear about to be embraced.

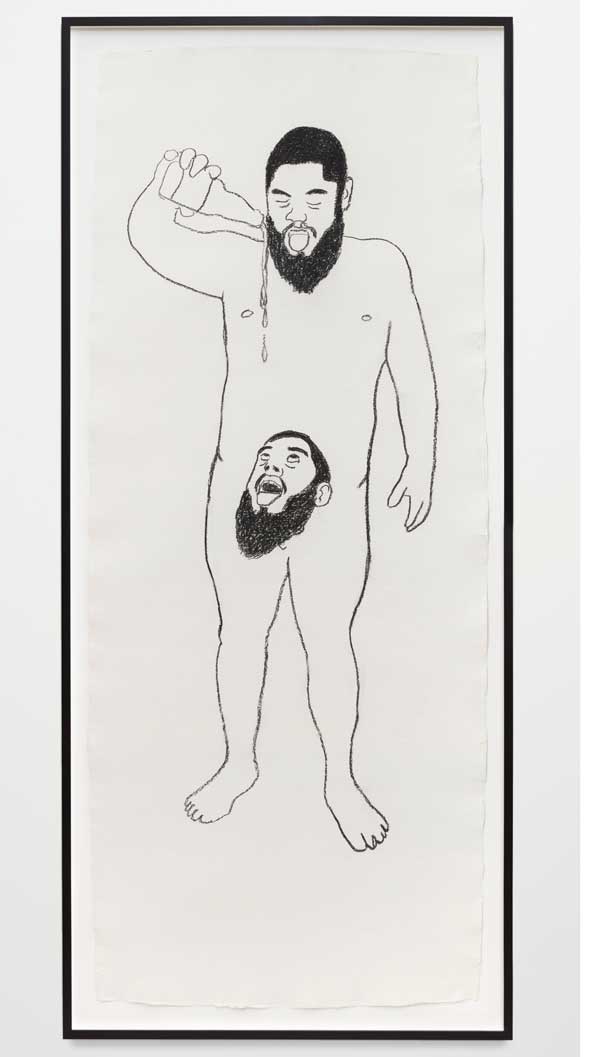

Flores further perpetuates the illusion (of sculpted forms signing for actual human beings) in a series of photographs, where he poses his doppelganger with his pregnant wife. The four images entitled Family Portrait are large-scale photographs of the couple standing on a gray-colored cloth backdrop in varying poses of affection. His soft yarn hands delicately touch his wife’s expectant belly. In addition to the photographs and sculptures, Flores includes large-scale charcoal on paper works from his Dickhead Series. Each of the eight drawings features a minimally rendered, naked representation of Flores› body with a more elaborately defined face. In place of his genitals, Flores draws a second full-sized head and the two interact, engaging in both masculine and absurd activities. For example, in Dickhead (Beer), the upper head looks down at the lower whose outstretched tongue waits for a trail of beer to fall into its mouth from a bottle he is holding. Though disconcerting, there is something satisfying about these crude and humorous pieces.

Flores employs self-representation to explore issues related to gender and identity. He creates sculptures using a traditionally feminine medium—crochet— and in doing so has positioned himself as an artist who is not afraid to make works that express machismo, as well as intimacy and sensitivity. As seen in the video that opens the exhibition, by exposing his real self, he gives his stand-in strength and complexity.