“Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else,” wrote Italo Calvino in Invisible Cities. In an “Alternative Guide to the Universe” there are many fabulous cities; creations somewhere between Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and William Blake’s Jerusalem. What unites these fictional spaces, which include Marcel Storr’s elaborate Megalopolis drawings with their sky-scrapping ziggurats and minarets in jewel-like washes of color, William Scott’s utopian, gospel-driven re-imagings of San Francisco and Bodys Isek Kingelez’s visionary Congolese cities, is the artists’ desire to understand the universe in ways that will not only unlock its secrets but propose new and more meaningful ways of organizing how we live.

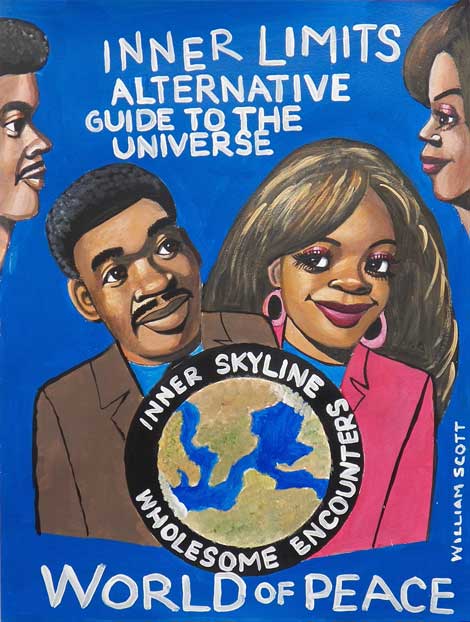

William Scott

SFOs The Skyline People of Wholesome Encounters Of A New Science Fiction Future (2013)

© Creative Growth Art Center

Courtesy of Creative Growth Art Center

Most of the artists are outsiders in some form or another—autodidacts, fringe physicists, poetic engineers and dreamers—who have developed their “practices” and obsessions outside official institutions and beyond established disciplines. Breaking free from the strictures of conventional thought they have created the sort of parallel universe experienced by children or scientists working on the very edge of what is known.

What they have in common is a desire to make sense of the seemingly random and unknowable. Number systems abound. George Widener predicts that someday his work will be understood by super-intelligent machines. While Alfred Jensen’s grids, with their interplay of Mayan number systems, Pythagorean thinking, and ideas borrowed from Ancient Chinese and Egyptian culture, make arcane connections between number theories, color principles, philosophy, astronomy, the I Ching and religion. The complexity of his colored numerical grids seems quite arbitrary and mad until one remembers the endless pages and ribbons of numbers of the recently decoded Human Genome Project, which identifies all the 20,000-25,000 genes in human DN and determines the sequences of the 3 billion chemical base pairs that go to make it up. To a non- scientist these dense lists look just as impenetrable as Jensen’s grids, though one is defined as outsider thinking, while the other is now mainstream science.

Installation view of works by ALFRED JENSEN at ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’ exhibition, Hayward Gallery 2013

©ARS, NY and DACS, London 2013, Photo: Linda Nylind

Here we are constantly reminded that the ideas of savants, the autistic, the visionary and the genius all sit along a moveable scale. As Paul Laffoley wrote in his 1991 publication The Bauharoque: “Religions, morality, mysticism and technology converge…” His Thanaton III is more than just a painting. After an apparent series of encounters with an extraterrestrial named Quazgaa Klaatu, the alien showed him how to make the painting into a phsyochtronic or mind-matter interactive devise for “balancing the forces of life and spirit; human and alien.” Mad? Who is to say? But Laffoley, grew up in Cambridge, Mass, and had a conventional enough education studying art history, philosophy and classics at Brown University, before a brief spell pursuing architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Canadian Richard Greaves, who lives in Quebec, studied theology and hotel management (is there a clue in this eclectic educational pairing with his chosen path’?) Now he lives in the remote Beauce forest creating vertiginous Babel-like structures from found materials held together with knotted string. As opposed to the right angel, which is based on reason, Greaves architecture is one of the instincts and emotions. His constructs might be the remains of a lost civilization, an apocalyptic vision or simply a series of eccentric playhouses for children. As he says, “It is my own story. Each house is a child I have made.”

Installation view of works by GUO FENGYI at ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’ exhibition, Hayward Gallery 2013

© the artist

Photo: Linda Nylind

Within this alternative universe are a number of maverick photographers. The homeless Lee Godie’s poignant, yet somehow triumphant, photo-booth self-portraits stand out in their assurance and pre-figure the work of Cindy Sherman. While there are a number of woman artists, including Guo Fengyi, with her schematic drawings that chart the flow of energies, the majority are men. Given that aspergers, autism and OCD are more prevalent among males, this is perhaps not surprising.

But to dismiss these brilliant mavericks as simply insane would be a mistake. Farfetched, outlandish and eccentric as their work may seem much of their thinking rivals that of scientists working on the wildest shore of science. We are invited to see the imagination as the jewel in the human crown. Art, mysticism and reason come together to create a visionary space beyond normal experience. For some of these artists their work may be a sane way of dealing with their demons but who are we to say that their visions are so different to those of Albert Einstein or Leonardo Da Vinci?

Sue Hubbard is an award winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic. Her recent books include her novel Girl in White (Cinnamon Press) and a new poetry collection The Forgetting and Remembering of Air (Salt)