“To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it the way it really was,” wrote Walter Benjamin. “It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” Dexter Dalwood, a previous nominee for the Turner Prize, examines in this new exhibition how history is constructed, interpreted and remembered through the making of paintings and how it might continue to be painted. London provides a topos for this exercise in representation. It has long been a setting and subject matter for the artist but here he gives an idiosyncratic take on the city as specific sites and locations are reconstructed from a collage of personal, as well as cultural memories, and political history.

Born in Bristol, UK, in 1960, he was a member of the Cortinas, a punk band, before studying at Central St. Martins and the Royal College of Art. Many of his past images have been culled from popular culture, including Kurt Cobain’s greenhouse and Lord Lucan’s hideout. The “London Paintings” signal something of a shift from a rather formal stance to one that is more fluid and interpretive. From the first there are interwoven quotes from art history; from Picasso, Walter Sickert and the Camden Town painters, as well as Patrick Caufield. The Thames below Waterloo (all works mentioned are 2014) not only nods at Monet’s paintings of London but, with the inclusion of the area of bright swimming-pool-blue at the bottom of the canvas, to David Hockney’s California paintings. To walk around Dalwood’s exhibition is a bit like a game of painterly charades or guess the artist. There are hints, references and seductive clues that make demands of the viewer in an unstable and slightly inchoate world. Interpretation is never quite within reach. In Half Moon Street, a bunch of flowers in a vase on a small round table in a predominantly blue room seems to suggest late Picasso, while the seedy Interior at Paddington, with its cheap brocade-red glow from a lamp, might be a brothel as well as a reference to the Camden Town painters and a bow to Patrick Caufield. One of the most beautiful paintings (if that’s a word that Dalwood would accept about work that remains in its fluidity and eclecticism relentlessly postmodern) is Old Thames. The outline of a black barge against the gray river suggests not only Whistler in its unassuming intensity but, in the repetition of the small waves, something of the mark-making of a Japanese woodcut.

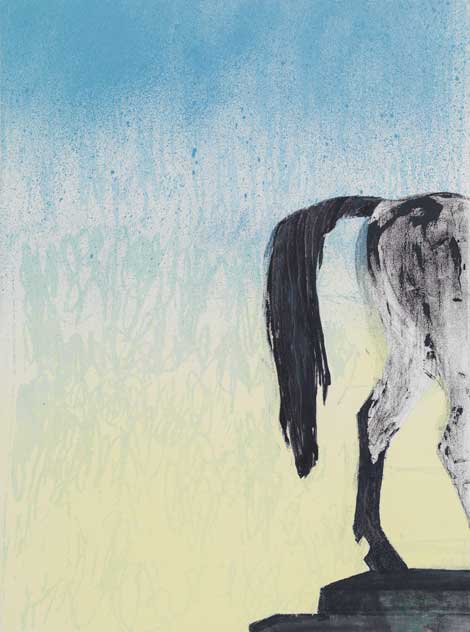

Typically Dalwood’s works depict imagined or fabricated interiors devoid of the human figure. His canvas of the Old Bailey shows the high court emptied of both the accused and the judiciary. Suggested by the recent Murdoch phone-hacking scandal, its fiery hell-furnace reds and seat like a biblical throne of judgment, seem all the more potent. Another version of the court is depicted at night in black and white. Not only does this appear to make reference to newsprint and something rather filmic and Hitchcockian but suggests, with its flat areas of impenetrable darkness, the hidden shenanigans that go on in high places. There is humor too—as in 1989—Dalwood is not afraid to take on big and controversial subjects. Here the tail-end of a statue of a horse on a stone plinth is set against a pale London sky.

The date is the clue, for it refers to the Poll Tax riots, when miners and anarchists climbed on scaffolding and sculptures during the protests that affected British towns and cities during dissent against the poll tax (a local tax officially known as the “Community Charge”) introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. There’s a certain wit and irony that the backend of a horse, a conventional 19th-century statue of a General or member of the establishment set on a pedestal high above a London street, depicts the rump of the ruling class in retreat.

There is a persistent loneliness and sense of alienation at the heart of Dalwood’s work in these atmospheric, silent interiors devoid of human presence. They are dreamscapes; romantic, melancholic and enigmatic. Poetic intensity is continually undercut with the work’s postmodern rawness and insouciance of assembly, the flat, often scruffy and casual-looking surfaces and areas of color.

Dalwood is concerned about finding meaning in lived and shared experience, a sort of social realism that creates mythical narratives though the appropriation of different viewpoints and sources of knowledge. Unusually for an artist influenced by and steeped in our transient consumerist society, he has said that “by making connections between all areas of visual culture I find that there is the possibility of presenting a worldview which prioritizes what is important, while at the same time including, or making space for the insignificant.” To return to Walter Benjamin, he “seize(s) hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” Past and present coalesce in transformative scenarios that not only question the processes of memory and our relationship to the past but continually scrutinize the power of painting to examine these themes.

All images courtesy of the Simon Lee Gallery and the artist.