Martin Creed’s new exhibition—he of the 2001-Turner-prize-winning-light-bulb-turning-on-and-off-fame—is witty, playful, occasionally insightful and often very irritating.

The exhibition spans the entire Hayward gallery and ranges from a spot of barely noticeable Blu-Tack indented with a thumbprint, to a solid brick wall built outside on the roof. Creed likes things that move. There’s a vast revolving neon sign à la Bruce Nauman in the first gallery that says, with what might or might not be Freudian intent: “MOTHERS.” Then there’s a car that flaps its doors as the wipers swish back and forth and a grand piano where the lid springs open every 15 minutes. Also, out on the roof, is a large black-and-white video of a penis becoming erect and then gradually wilting. The day I went it was very cold and wet and it looked rather forlorn; a very bored gallery assistant was playing endless single notes on a piano.

Even the title “What’s the point of it?” cleverly preempts criticism. Creed is big on ambiguity: “I find it difficult to make judgements, to decide that one thing is more important than the other. So what I try and do is to choose without having to make decisions.” At the same time, he insists, “a non-decision is still a decision, and to choose everything is still to decide.” Just as well he’s not running the country then.

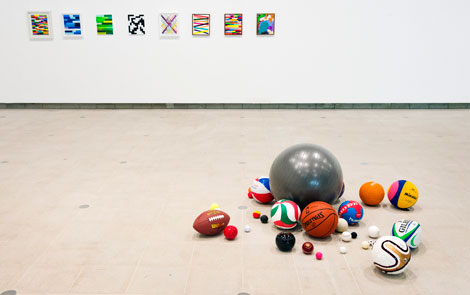

Martin Creed, “What’s the point of it,” installation view,work no. 1092,2011, Hayward Gallery. © the artist. Photo Linda Nylind

Creed doesn’t have a signature style. He works across a vast array of media using cardboard boxes, masking tape, film, sculpture and marker pens to create an array of work from stylish minimalist drawings, including a wall of prints made with halved heads of broccoli, to a room filled to the point of claustrophobia with white balloons. He treads a precarious line between the considered, the amusing and the downright annoying. There is a screwed up ball of paper in a glass case, a row of nails banged into the walls that cast shadows, and the famous light that goes on and off. If being a contemporary artist is about making the viewer see the world differently then he passes muster. But what he asks us to see isn’t always worth the effort. The video of the defecating woman—as he so sagely puts it “shit [is] the first solid thing any of us makes;”and the vomiting man who is expressing “horrible feelings” that “you can’t paint”—is that they are not very interesting either visually or conceptually. There’s a sense that he’s made it simply because he can. That he’s having a gas. The trouble is that much of the work is reminiscent of something else. The collapsing piano was executed with greater flair by the German artist Rebecca Horn some years ago at Tate Britain, and the pregnant protrusions of the white gallery walls were previously rendered by Anish Kapoor. On a single sheet of framed white paper, written in small type, are the words “fuck off.” It’s as if Creed wants it both ways. To be taken seriously but to laugh at us if we do try to “make sense” of the work.

Martin Creed, “What’s the point of it,” installation view,work no. 1092,2011, Hayward Gallery. © the artist. Photo Linda Nylind

Some have called him a conceptual artist, to which his response is: “I don’t believe in conceptual art. I don’t know what it is. I can’t separate ideas from feelings… work comes from feelings and goes towards or ends up as feelings. It is a feeling sandwich, with ideas in the middle.” This, of course, means nothing. And that surely is the point. He doesn’t want to be pinned down. He doesn’t want us to be able to say whether something is good or bad. He wants to keep us guessing. When Duchamp stuck his urinal in a gallery in 1917, that was a statement. The allusion to bodily fluid must have been shocking to polite society. Piero Manzoni tinned his shit in 1961 and in 1987 Andres Serrano placed a small crucifix in his urine and called it Piss Christ. We’ve seen it all before and the joke and the shock value have worn a bit thin.

Creed doesn’t necessarily like the word “artist.” He’d rather be known as a bloke who makes things. It’s just that in a world of potential climate change and war, famine and fundamentalism, what he makes and asks us to consider is so very slight. Creed likes crosses “because they are neither horizontal nor vertical, and because they are like kisses.” Really? You can’t imagine a scientist, a philosopher or even a politician getting away with something so intellectually flimsy, of “choosing without having to make decisions.” But there seems to be a special clemency at work because he’s an artist.

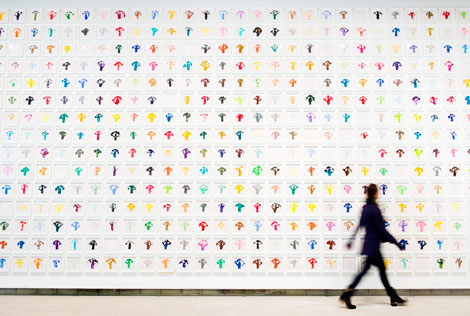

Martin Creed, “What’s the point of it,” installation view,work no. 1092,2011, Hayward Gallery. © the artist. Photo Linda Nylind

Martin Creed, “What’s the point of it,” installation view,work no. 1092,2011, Hayward Gallery. © the artist. Photo Linda Nylind