Artist Liz Glynn has been taking on increasingly ambitious projects by leaps and bounds, and lately more of it can be seen on the East Coast, where she’s from, than on the West Coast, where she is now based. In early 2017 she had an installation on a corner of Central Park in New York City, “Open House,” in which sofas and armchairs from the Gilded Age were replicated in concrete, and posited in public for all to ponder and to place their tired bodies upon. In October she unveiled “The Archaeology of Another Possible Future” (through Sept. 2018) at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) in North Adams, Massachusetts, a former manufacturing town trying to remake itself as an arts destination. Hulking industrial buildings have been converted into 250,000 square feet of raw space, exhibiting mostly large-scaled works by artists such as James Turrell, Jenny Holzer, and Sol LeWitt. In 2015 museum curator Susan Cross invited Glynn to create artwork for Building 5, which is nearly a football field in length.

Liz Glynn, Moore’s Law, 2017, courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, photo by Steven Probert.

“Archaeology” is in five sections, a kind of fractured fairy-tale ride through a selective history of labor and manufacturing, and of our transition from a material to a digital culture. Entering from the second floor of the previous building, one has an overview from the top of a flight of stairs. The first section, “Analog,” is comprised of three monumental stacks of wooden pallets—the kind used in warehouses—arranged in pyramidal shapes. Inside each is a space evoking different senses—including smell (scents are placed in ceramic vessels) and touch (swaths of thick felt dangle from overhead). In section two, “The Shape of Progress,” the artist refers to a dozen ideas, including “The Fiscal Cliff” and “Ripple Effect.” In “Household Activities,” two stacks of colored blocks illustrate how much time men and women spent on daily domestic chores in 2015—with women, of course, still spending significantly more time sprucing up the home. In section three, “Speculations,” three shipping containers present yet more riffs on labor and manufacturing—in one, visitors might encounter a former factory worker (a real one) recounting what it was like in the days when people actually made things; another is filled with drawings of failed inventions; and the third has three videos which address Y2K doomsday predictions, performances in industrial spaces, and workers disappearing into thin air.

There’s a certain nostalgia embedded throughout this breathtakingly inventive opus, but I don’t think Glynn intends for us to retrace our steps back to the Industrial Revolution. As she said during our walkthrough, “Human progress in our economy is generated but at what cost is the question?”

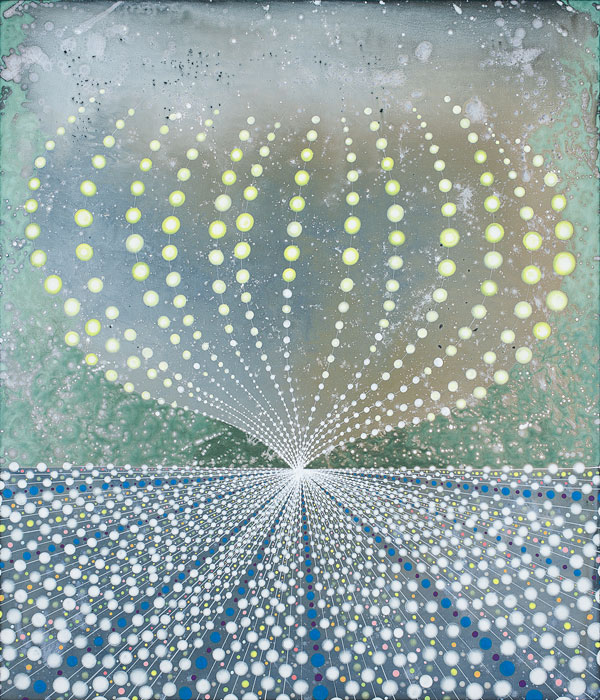

Barbara Takenaga, Green Light, 2013, courtesy of Williams College Museum of Art and Bruce and Donna Polichar.

While in that part of the world, I also had a chance to see Barbara Takenaga’s stunning retrospective at the Williams College Museum of Art (through Jan. 28, 2018) in Williamstown. Her meticulously painted canvases are as contemplative and cosmic as Glynn’s work is extroverted and rooted in current events and material realities. The Takenaga show begins two decades ago with her turn to a series of abstractions, and the 1998 painting Tortuca shows an array of spidery spirals overlaid on a background that shifts from light beige in the center to brown on the edges. The work was inspired by a cowlick on her dog, but she also understood that something so mundane was in the pattern of the universe. Takenaga’s body of work evokes cosmological phenomena—falling stars, the Milky Way, time-space vortices. Critics have suggested similarities to psychedelic art and Op Art, but it is completely singular. Over time her spirals were paired with dots, dots became orbs—made dimensional through color and shading—and then spirally strands of pearls would pass under and over one another. In this decade the horizon line has appeared in her work, perhaps, as exhibition curator Debra Bricker Balken has suggested, due to the death of the artist’s mother and the tragedy of 9/11, both in the same year. We see the limits of our existence, and it is the horizon.

Barbara Takenaga, Sphere Horizon, 2013, courtesy of Williams College Museum of Art and Bruce and Donna Polichar.

The artist paints with acrylic on linen, occasionally on wood panel, and it is astonishing work. How does she manage hundreds of dots/orbs the same size, or even more virtuosically, in ascending and descending sizes? How does she limn these perfect undulations that whip around and connect everything? In person you can see the slight irregularities of freehand painting, and more recently in such paintings such as Green Light (2013) and Night Painting (JFM) (2016), she lets the backgrounds bleed and splatter, and allows herself to experiment with happenstance. Over that she overlays her deliberate, rhythmic patterns, which must tap into the music of the cosmos—I say “must” because we are viscerally drawn to them, as if they were keyed into our DNA.