In the earliest days of his unlikely, unfortunate campaign for president, billionaire Donald Trump declared in 2015: “Sadly, the American dream is dead,” adding special emphasis on the last word, delivering the bad news like a judge slamming down a gavel. As in many things uttered by our gilded president, the truth lies somewhere in the opposite direction, with Americans still grasping for greater wealth or at least the illusion of prosperity. If anything, the American dream has only grown larger and more frantic the last quarter-century, and photographer Lauren Greenfield has been there to document the wild cultural shifts.

For many of those captured in the pictures of her “Generation Wealth”—both a career-spanning book and an exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography—conspicuous consumption is a lifestyle and a religion. What was once considered crass in these United States is now understood in the era of Trump and Keeping Up with the Kardashians as a sign of winning. Without flash and some glistening bling, you are simply a loser.

The exhibit begins with an image at the beach, and the same picture that was the cover of Greenfield’s 1997 book on modern youth, Fast Forward: young people are cruising in convertibles by the boardwalk in Santa Monica, carefree and affluent, vibrant bodies on display. It’s a classic Southern Californian scene, and the distance between the classes is less profound here.

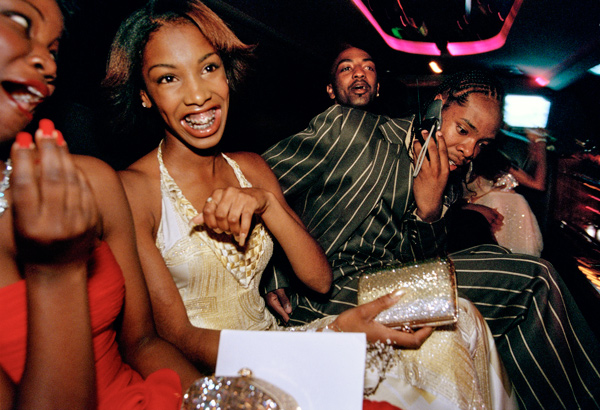

Crenshaw High School girls…Culver City, California, 2001

In other pictures, we meet adolescents with deep-pocket parents: a 13-year-old boy on the dance floor of an extravagant Bar Mitzvah at the Whisky a Go Go, leaning a little too close to a dancer’s prominent breasts; a girl at a July 4th pool party just days after her nose job sits peacefully with family, bandages covering the center of her face. In most cases here, people are thrilled to see the camera pointed at them, to strut their threads, their new faces and piles of cash.

The American upper classes have been documented before, including by the likes of Tina Barney, whose large pictures (often of her own well-off family members on the East Coast) are like romantic paintings. Greenfield is also from an upscale background and attended the same Los Angeles private school as some of her subjects, but she’s more of a classic documentary photographer, where the environment is an essential part of the whole. Like the book, her Annenberg show takes an encyclopedic approach, collecting a mountain of compelling photojournalism—with a clear emphasis on the journalism. It’s that approach that led her to a smooth transition into documentary filmmaking, delivering meaningful content and storytelling for HBO and elsewhere in work that shows a still-photographer’s eye. In “Generation Wealth,” Greenfield spends as much time exploring the yearning and struggles of people who at least want to appear to be living large. There is the teen who has learned to fake the affluence of his classmates, desperately scrimping to purchase bits of Cartier and Dior; a homeless woman at 67 beams next to her imitation Louis Vuitton bag; and a 17-year-old dude in pinstriped zoot suit picks pick up his prom date in a limo in South Central LA.

Photographer and former model Ilona in the mezzanine library of her home, Moscow, 2012

One video screen presents the Greenfield short film Kids + Money, as adolescents grapple with issues of finance and image. One teenage boy spends $700 to $800 a month on clothes and says, “Hopefully, I can give up this addiction.” Later, a precocious 12-year-old girl has become aware what “Made in Indonesia” means in terms of child labor, and what it should mean to her as a shopper. “I feel guilty for a minute,” she says; then adds, “These jeans are amazing. I’m going to buy them anyway.”

A side room at the Annenberg titled “Make It Rain” captures a scene of strippers and the flashy dudes who shower them with one-dollar bills, suggesting a level of performance on both sides of a very public transaction. The façade falls away in a large photograph of a nude stripper in stilettos on her knees clawing at a pile of singles on the floor.

A wall dedicated to “The Cult of Celebrity” announces itself with a huge, startling image of 6-year-old pageant winner Eden Wood, already practiced in the look of beauty and utter insincerity, gleamingly blonde and blue-eyed, her tongue curled upward suggestively. Barely out of her toddler years and dressed in frilly pink, she’s commodified and corrupted for modest fame and fortune, on her way to temporary stardom on reality TV’s Toddlers and Tiaras.

More lasting is the fame of Kim Kardashian, seen here in a 1992 picture as a 12-year-old girl at a Bel Air school dance, looking passively into the lens she will soon call home. She’s pampered but still far from becoming the ultimate consumer and narcissist she is today. (Her own book, Selfish, is 448 pages of selfies, starting with a cover showing her heaving breasts pressing toward the camera.) We also see her in an image from the more recent past, as the lucrative reality TV star stands serenely at the trunk of her car while surrounded by a pack of paparazzi (including a teenage boy).

Most of the pictures in “Generation Wealth” are from the United States, with occasional trips overseas to include the common ailments of mass foreclosures and dehumanizing greed, casualties along the way to emulating the unreachable American dream. We see people in countries and regions with proud, rich cultures (Asia, Europe, the Middle East, etc.) that are centuries older than the United States, turning westward to emulate the manners, styles and excessive consumerism of the Great Satan, funded by debt and shaky loans even in the richest of countries.

Lauren Greenfield, Russell Simmons, cofounder of Def Jam Recordings, and Brett Ratner, film director and producer, at L’Iguane restaurant, St. Barts, 1998

It’s an unwinnable battle for most. In the U.S., the early postwar years were a time of shared affluence, with unprecedented access to comfort and education in a swelling middle class, at least for families headed by white males. There was a new wave of home ownership and college degrees through the GI Bill. But by 2017, the executive class had left the working classes way behind. The disparity in compensation between top CEOs and workers is now 347 to 1—nearly six times the ratio in the Reagan ’80s. The resulting stress on the common American dreamer is easily charted through Greenfield’s work.

The morning after the crashes has been devastating internationally, with neighborhoods of foreclosed homes abandoned to the elements, and the broken people forced to leave their dreams behind. One notable exception shown by Greenfield is the Iceland fisherman-turned-banker who happily returned to working on a trawler at sea after the economy turned nasty. He is among the few heroes in “Generation Wealth.”

The style and point of view in these pictures and video content is consistent through the years, seamlessly moving from slide film to digital, from the early ’90s to now. But Greenfield’s work reached a new level of empathy with Thin, a 2006 film and photography essay that captured young women struggling with self-image and eating disorders, clouded by body dysmorphia and endless media depictions of perfection. It’s an ailment that transcends class, but not everyone can afford a solution. The exhibition includes a section called, “New Aging,” examining the horrors of plastic surgery, the pain and abuse it requires for a chance at approximating youth. (It is, after all, surgery.)

Lauren Greenfield, Jackie and friends with Versace handbags at a private opening

at the Versace store, Beverly Hills, California, 2007

The Annenberg show is sensory overload, with nearly 200 pictures and an infinite loop of video footage and more stills on a variety of high-tech screens. An accompanying exhibition across town at the Fahey/Klein Gallery is much more selective, offering a smaller show with an eye toward identifying single images that stand alone—not just as journalism but photography as collectable art.

One photograph there presents a row of fashion models backstage at a 2009 Prada show standing utterly blank and mannequin-like, looking as strange as a scene from David Lynch. There’s also an extreme close-up of a Jesus medallion, which has jewels for eyes and a crown of thorns transformed from a symbol of holy sacrifice into yet another layer of bling. The look of shock frozen on his golden face seems entirely appropriate.

©Lauren Greenfield. All photos ©Lauren Greenfield, from the exhibition “Generation Wealth,” courtesy the Annenberg Space for Photography.

Generation Wealth by Lauren Greenfield at Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, runs through August 13, 2017; annenbergphotospace.org