Laurie Lipton’s supremely detailed large-scale graphite drawings document the haphazardness of modern life as well as the darker more sinister underbelly of consumerist culture. Looking at these images, one can’t help but be reminded of how the proletariat is controlled and all human freedoms are denied in Orwell’s 1984. Lipton’s sardonic content connects with today’s bleak and unsettling political climate with imagery seeming to stem from a sense of hopelessness. Yet there is also a humorous aspect to these drawings. For example, in Off (2013), a woman who looks like she belongs in a 1950s issue of Good Housekeeping stands next to a refrigerator filled only with glass jars and old crumpled cans. The cupboards behind her are also stuffed with old cans, yet her smiling expression gives us the impression that all of this is completely normal. Perhaps she is a hoarder for the new millennium? Perhaps this is the status quo, the way things have always been? Either way, the image is vaguely unsettling.

Off, 92.25″ x 69.5,” charcoal & pencil on paper, ©LLipton

Death and the Maiden, 2005, 17′ x 13.4′ pencil on paper

Much of Lipton’s work deals with death, whether it be the demise of human consciousness—as in her most recent drawings wherein human beings appear to be controlled and brainwashed by various sundry electronic devices—or, more literally the skeletal figure presiding over the living world, as in Death and the Maiden (2005), where a little girl is seen lying in her bed, embracing a skeleton. As with her other drawings, the central figure appears oblivious to the situation, seemingly hopeful, gazing off into the distance, a smile at play across her face. Even in images where death is not explicitedly represented, there is the intimation—as in Celebrity (2006), where a beautiful young woman is seen standing in front of a phalanx of cameras. We cannot see the photographers’ faces; only the giant invading single eye of each camera. The woman turns away from the cameras, toward the viewer, her eyes pitch black—reflecting the same vacant stare of the camera lens. A mortal void is implied as the woman appears to be an empty vessel, staring out into space, her fingers like claws, grasping at air.

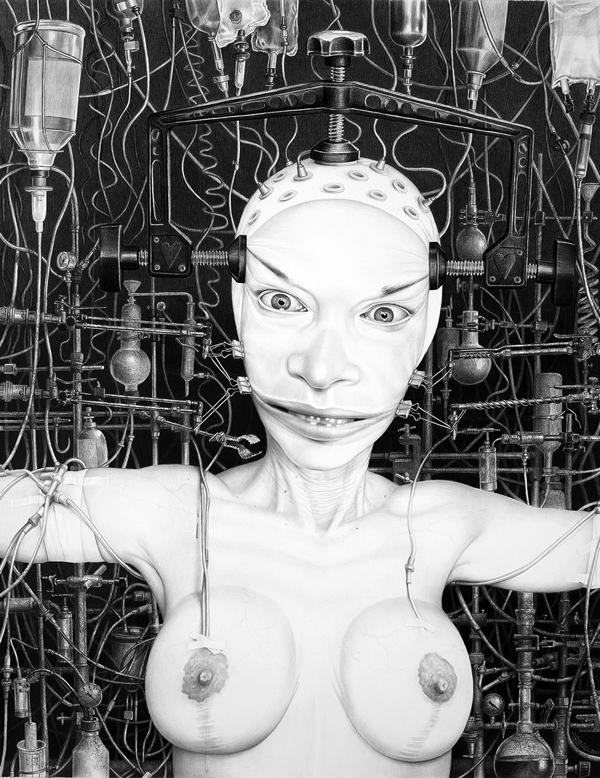

Enhanced, 2011, 38″ x 29,” charcoal & pencil on paper, ©LLipton

Lipton also links death to our obsession with youth and the measures we will take to cling on to it. In Enhanced (2011), a young woman is naked from the waist up, her face and breasts pulled and contorted by various electrodes, tubes and probes attached to her skin. Her eyes are wild and her face reflects again the same strange vacancy that informs Lipton’s other images as though the young woman was being transformed into a mechanized, programmable being; her humanity slipping away, not unlike the Stepford wife.

Whether these images deal directly with the notion of death and our place in the cosmos, or refer more indirectly to our pervasive lack of human responsibility as stewards for the planet, Lipton is keenly aware of our place in the world, with pencil in hand.