In order to kill time while waiting for John Waters to take the stage for a Conversation to celebrate the publication of his new book, Mr. Know-It-All, at the Renberg Theatre in Hollywood, I made the mistake of checking my phone. One email awaited me. It was from a prominent New York literary agent, responding to a 50,000-word slab of prose I’d sent him two weeks earlier. The brief note concluded with the words: “I’m afraid it’s a pass from me.”

I’d barely had time to read it when the lights dimmed and John Waters strode across the stage to massive applause from a sold-out house. I needed time to process this rejection. Against my better judgment, I had allowed myself to get my hopes up, and my spirits were now plummeting into abject dejection.

Mr. Know-It-All cover, 2019.

Waters was already on a roll, rattling off sparkling anecdotes and shrewd observations in response to Merrill Markoe’s thoughtful questions. He was putting forward the ingeniously subversive notion that gay men and gay women should start having sex with each other in order to really throw the straight world for a loop. He was poised, provocative and unpredictable. This, after all, is what he has been doing for years: writing books, then traveling around the globe regaling reverential audiences with his brilliantly polished anecdotes and opinions. As he said, he’s on a plane almost every day. He possesses great sharpness of mind, generosity of spirit, and he has a great attitude.

Of course he does, I thought, as I slumped further into my seat: a little appreciation makes all the difference, and a lot of it probably makes a lot of difference. I’m guessing that it’s hard to remain sour for very long when you’re at the mercy of so much love.

Divine, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole, David Lochary, John Waters, and Danny Mills on the set of Pink Flamingos, 1972.

Surrounded on all sides by adoring laughter, I brooded over the sudden, blunt rejection of the epic prose undertaking I’d been overextending for the last three years. After years of struggling with form, I finally acknowledged that I had no grasp of plot, character or dialogue, and decided to write a novel. It’s a somewhat intricate and multilayered work of ultra-metafiction, not exactly what I had in mind, but it’s all I’m capable of – hence the lengthiness of the extract I sent the Agent, to give him an idea of the labyrinthine extent of it. Hell, he had even said he was looking forward to reading it.

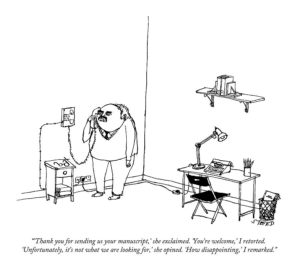

Edward Steed, “Thank You For Sending Us Your Manuscript,” 2016.

I couldn’t help getting my hopes up again. I have a certain amount of confidence in the work – until it’s squashed by the judgment of somebody in a position of power. Agents, after all, are the pivotal middlemen of the literary world, and this one (the introduction had been set up by a friend; there is no other way) had claimed, in an earlier email, that he was receptive to ‘misanthropic’ work. It was this statement that raised my hopes. But perhaps there were limits to his appreciation of (or tolerance for) misanthropy. I should never have checked my phone. Rarely did anything good come from succumbing to this insidiously-manipulated urge.

I now resented the honest assessment I’d asked for. In his brief and blunt note the Agent suggested that my endeavors didn’t add up to a novel but would be more effective if reworked into comic essays in the manner of David Sedaris. Perhaps my attempts at narrative had completely failed. Yet, in the Agent’s note, there was no indication that he had actually read the extract I’d sent him; there was nothing in those four lines that referred directly to the work itself. I suspected that he had cast it aside in disgust after suffering through a few random paragraphs. The oblique brevity of his response seemed to suggest that he recoiled from the prospect of being connected with something so distasteful.

Only too well did I know how tiresome it was to be drawn into a lot of back-and-forth with needy scribblers. I am frequently called upon to critique or edit the work of friends and acquaintances, and seldom do I find the experience—always gratis— to be gratifying. Usually, I take a cursory look at as much of it as I can stand, offer some half-assed encouragement, and hope that’s the end of it. Doubtless, the Agent just wanted to get me off his back as politely and painlessly as possible, and move on to dealing with something more saleable.

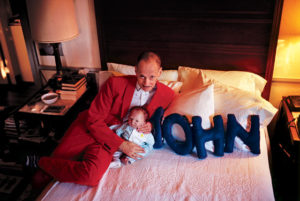

John Waters by Nan Goldin.

“Logjams… mudslides… gravy.” I emerged from my morbid slouching haze as Waters was lamenting how certain colorful phrases have fallen out of the gay vernacular in recent years – none of which left much to the imagination. “The only good thing about dying is that you’ll never have to shit again,” he remarked. I managed to grind out a few weak chuckles where, in better form, I would have laughed uncontrollably. Everyone loves John Waters. As they say, what’s not to love? The level of energy and engagement coming from a 73 year old was truly impressive. But, I reasoned, all the love and appreciation he receives must serve as a kind of fuel for vitality and charm.

As I sank back into the depths of despondency and assumed an ungainly slouching posture (there didn’t seem to be much point in sitting up straight now that I had tasted the bitter pangs of rejection), it occurred to me that Waters was one of those annoyingly admirable men whose lives seemed designed for the express purpose of reminding me that I haven’t lived fully enough or accomplished anything. And he has no qualms about enjoying his charmed existence. As he wrote in the book that we were gathered to celebrate the publication of: “Whatever you might have heard, there is absolutely no downside to being famous. None at all.”

John Waters, Eat Your Makeup (still), 1968.

Waters was talking about his family now, and how he reenacted the JFK assassination on his parents’ front lawn for one of his early films, Eat Your Makeup. But I couldn’t keep my mind on the stage for long, no matter how entertaining the conversation. I’m not one of those people who can easily brush off being brushed off, regardless of the credibility of the brusher-off. There are limits to the amount of rejection I can take. It discourages me and causes me to question myself. That’s why I don’t send my work out. A marginal member of the creative classes, loitering outside the gates of the literary establishment, I have always maintained a disrespectful distance from those who are best positioned to further my aspirations. But I’ve spent three years racking up over 100,000 carefully weighed words, so at this point it would be useful to receive some sort of feedback and encouragement, preferably from an influential stranger, in order to keep going and eventually close the deal.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t feign indifference to the discerning opinion of somebody who was clearly well-read and had what it took to rise to the top of his profession. Perhaps these last three years of pouring all my precious so-called creative juices into this dubious and ultimately flawed undertaking really had been a complete waste of time. But it was too late to stop now. Or was it? In any case, I certainly wasn’t going to break it down into palatable Sedaris-sized chunks.

It was seven o’clock, which made it 10 o’clock on the East Coast. It must have been a slow Saturday night in New York. Surely the Agent had better things to do. If not, I could imagine him resentfully resigning himself to the thankless task of reading my work.

I had been wondering how gently he would couch his rejection. “I liked your sardonic tone.” That was the consolatory bone he threw me. I derived no comfort from that. It doesn’t have a sardonic tone. If anything, it’s too heartfelt. But perhaps I wasn’t the best judge of my own work. I certainly wouldn’t be the ultimate judge of it. And there seemed to be something condescending about that “sardonic,” as if he was saying it to please me because he assumed it was something I strove for and took pride in. But maybe I was reading too much into it.

“Growing old, you have two choices: you either get fat or gaunt,” Waters was saying. Everything he said was quotable, but I was too distracted to take much of it in. “You know you’re old when you say that kids nowadays aren’t having as much fun as you did when you were young.” That was a good point. “Believe me,” he continued, “young people are having just as much fun hacking into other countries as we did dropping acid.”

Waters dropped acid last year, with another septuagenarian, Mink Stole, who advised: “If anybody sees God, please keep it to yourself.” Another eruption of genuine laughter shook the walls. (The description of this trip takes up a 25-page chapter in Mr. Know-It-All, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.) I wondered, cynically—“sardonically,” if you will—if Waters had deliberately embarked on this adventure knowing that he would be documenting it in a book that would be read by thousands of people.

John Waters, Mink Stole and Johnny Knoxville at the after party for the Los Angeles premiere of Hairspray, 2007.

We were into the Q&A now: Would he ever make another movie? Probably not. He’s already made 17, that’s enough. He has written six or seven books. The recent ones (Role Models, Carsick) have been bestsellers. He has no beef with Hollywood, they treated him fairly – and he certainly doesn’t have any beef with the publishing industry.

The convivial atmosphere of rejoicing in another writer’s latest success wasn’t the right climate in which to be soaking up my latest failure, and struggling to make sense of it. I had serious concerns that my novel-in-progress was unreadable. Perhaps when I looked at it, I saw only the ideal but not the actuality of what I was striving for – that which vividly exists in my head, but doesn’t necessarily manifest itself on paper. What was clear to me might not be so clear to a stranger. And now it had been assessed by an influential stranger and a negative verdict had been delivered.

Waters left the stage to thunderous applause. He would be taking a short break to hang out with his friends in the green room, before returning to the stage to sign books and have his photograph taken with about 200 people who were forming a line in the aisle.

I supposed that I had to craft a reply to the Agent. I considered the various ways of graciously framing my disappointment: “Thanks for taking a look, appreciate your thoughtful comments,” etc.. Or, gritting my teeth with rancorous self-pity: “Okay, here it is, here’s your David Sedaris-type essay. Hope you enjoy it.”