Double Horizon takes its title from Lia Halloran’s three-channel video installation composed from documentation of roughly thirty flights the artist made in the course of her training in air piloting and navigation and early aviation experiences over the greater Los Angeles area. In its play of continuous moving and transformed moving images, the work represents a significant departure from work that precedes and continues alongside it; but there is also continuity, as evidenced by the photographic C-prints from the artist’s Passage series, itself part of what the artist (who is also an accomplished skateboarding enthusiast) calls her Dark Skate work, exhibited in the adjoining galleries. Navigation and refraction are the commonalities between these bodies of work; and it might be said that Halloran has been juggling perceptual and phenomenological horizon lines throughout the course of her career.

For Halloran, no image seems perfectly static; merely like memory, imperfectly fixed. Attaching lights to her body, Halloran photographed herself on multiple skate runs through various popular skateboarding locations near or alongside the Los Angeles River, always at night, in peak darkness with the only light available emanating from structural illumination by way of built-in lighting elements or the surrounding urban environment at some distance or at least partially concealed from the site. With cameras set for long exposure (Halloran works with an assistant), Halloran’s skateboard trajectory registers as multiple strands of light variously leaping, looping, arcing, and skittering across the visual field, though not necessarily filling it. More than a trace or signature, it’s the architecture of an event rendered in line and light. In Bike Path (2018/2019, from the Passage / Dark Skate series), the trace begins in the left middle ground with light-lines converging into an enveloping arch that in turn becomes a portal to a triangulating loop ambling in a double parabolic leap to a small tempest of white sparks against an embankment as it winds toward a green border. The long exposure picks up and highlights location details in addition to Halloran’s careering lines: looming foliage and light standards, a couple of residential structures, the slick and briny surface of the Arroyo Seco channel, a tire that has rolled down the embankment to rest in the foreground, the serene grace of the more expansive parabola that forms the arch in the bridge that is the defining structure

For Halloran, no image seems perfectly static; merely like memory, imperfectly fixed. Attaching lights to her body, Halloran photographed herself on multiple skate runs through various popular skateboarding locations near or alongside the Los Angeles River, always at night, in peak darkness with the only light available emanating from structural illumination by way of built-in lighting elements or the surrounding urban environment at some distance or at least partially concealed from the site. With cameras set for long exposure (Halloran works with an assistant), Halloran’s skateboard trajectory registers as multiple strands of light variously leaping, looping, arcing, and skittering across the visual field, though not necessarily filling it. More than a trace or signature, it’s the architecture of an event rendered in line and light. In Bike Path (2018/2019, from the Passage / Dark Skate series), the trace begins in the left middle ground with light-lines converging into an enveloping arch that in turn becomes a portal to a triangulating loop ambling in a double parabolic leap to a small tempest of white sparks against an embankment as it winds toward a green border. The long exposure picks up and highlights location details in addition to Halloran’s careering lines: looming foliage and light standards, a couple of residential structures, the slick and briny surface of the Arroyo Seco channel, a tire that has rolled down the embankment to rest in the foreground, the serene grace of the more expansive parabola that forms the arch in the bridge that is the defining structure

It’s not all about the light lines (and flight lines—Halloran’s grace and virtuosity on the skateboard clearly play into the complexity of the ‘figures’ traced here). Halloran is sensitive to place and placement here, and has considered her locations thoughtfully. She finds the grace notes in industrial sites and civic infrastructure and knows how to play them. Foliage and riparian elements—even the Los Angeles River’s concrete ditch—soften this aspect.

Speed and stillness stand in stark contrast—in some locations more than others. A swan-diving line down an embankment in Bronson Canyon (2014/2019, Passage / Dark Skate) seems to ricochet as it descends into smoothly fluttering lines before rearing up cobra-like to fasten themselves to the other side. The gravity of the moving body seems more evident in the secondary light ‘shadows’ cast upon the ground beneath, while trees and landscape stand sentinel. Notwithstanding the signature flourish of the lines, we feel the actual imprint, the physical impact is elsewhere. Even in such a contained space, Halloran has a way of considering by inference a scope well beyond it.

Speed and stillness stand in stark contrast—in some locations more than others. A swan-diving line down an embankment in Bronson Canyon (2014/2019, Passage / Dark Skate) seems to ricochet as it descends into smoothly fluttering lines before rearing up cobra-like to fasten themselves to the other side. The gravity of the moving body seems more evident in the secondary light ‘shadows’ cast upon the ground beneath, while trees and landscape stand sentinel. Notwithstanding the signature flourish of the lines, we feel the actual imprint, the physical impact is elsewhere. Even in such a contained space, Halloran has a way of considering by inference a scope well beyond it.

The location elements are not always so still. Halloran manages to engage the elements as an action or event of extended duration assumes a choreographed aspect, as in the Griffith Park Wash (2017/2019, Passage / Dark Skate). There’s a rhythmic as well as architectural variety to the light inscription here, with a zig-zag of jagged leaps and sudden jumps settling into a momentary undulation; a sharp vertical leap and plunge over into a syncopation of arcs and sonic-wave flutter. The trees become a chorus here, registering, inclining, seemingly bending and weaving to the movement. This is a location I know well but which here seems entirely transformed.

The location elements are not always so still. Halloran manages to engage the elements as an action or event of extended duration assumes a choreographed aspect, as in the Griffith Park Wash (2017/2019, Passage / Dark Skate). There’s a rhythmic as well as architectural variety to the light inscription here, with a zig-zag of jagged leaps and sudden jumps settling into a momentary undulation; a sharp vertical leap and plunge over into a syncopation of arcs and sonic-wave flutter. The trees become a chorus here, registering, inclining, seemingly bending and weaving to the movement. This is a location I know well but which here seems entirely transformed.

The lighted bridge/walkway section of Sepulveda Dam (2014/2019, Passage / Dark Skate) Halloran shows us is not so easily transformed by one human’s intervention, whether performance or landscape photography. But Halloran makes the most of this stark counterpoint, contrasting the careering lines of the moving object (her body) that alternately tie themselves into knots near the embankment, or arc and disappear into the sky, against the stolid forward projection of the massive concrete piers and their light standards punctuating the horizon. There’s a kind of rhythmic contrast here, too, with the soft foreground meander of the ground shadow reflections offset by a spectacular arc into that seems to rear backward towards the viewer.

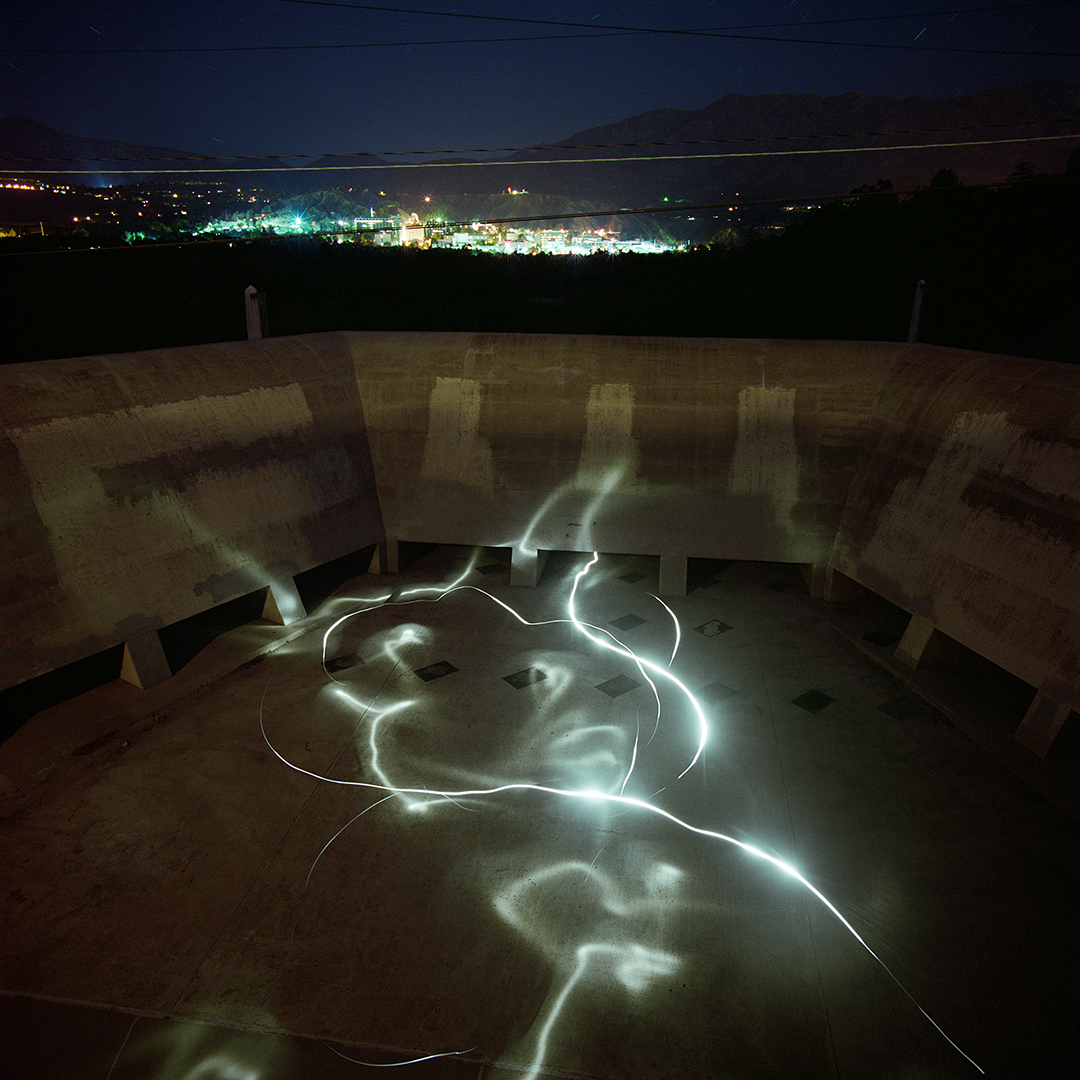

The Devil’s Gate section of the Arroyo Seco wash is a favorite location and it’s easy to see why Halloran returns to it frequently. Aesthetic and utilitarian aspects intersect and comfortably serve each other here. In Above Devil’s Gate (2014/2019), you could easily mistake the undulating lines on the floor of the basin or terrace here for those of a figure skater. The lines themselves seem to trace vessels more than figures (or possibly apples and pears—a still life out of moving light), as if to spell out the vessel of light Halloran has made of it. Above the walls of the dam or break, we see the ridge line and the shallow ellipse of another cluster of glittering lights below—the JPL campus. She reverses the setting and the aesthetic in the quasi-minimalist, intensely concentrated Devil’s Gate (2014/2019), where she turns three regular perforations in the dam wall into frames for a kind of stop-action trace of the moving figure. We can ‘read’ the image several ways. The softly fluttering ribbons of light seem to collide in the center frame sending off a starburst of arcs and loops. In the meantime, the mass of blackened wall set against the sapphire blue of the sky above it (itself striated with power lines) elicits a kind of Ellsworth Kelly elegance.

The Devil’s Gate section of the Arroyo Seco wash is a favorite location and it’s easy to see why Halloran returns to it frequently. Aesthetic and utilitarian aspects intersect and comfortably serve each other here. In Above Devil’s Gate (2014/2019), you could easily mistake the undulating lines on the floor of the basin or terrace here for those of a figure skater. The lines themselves seem to trace vessels more than figures (or possibly apples and pears—a still life out of moving light), as if to spell out the vessel of light Halloran has made of it. Above the walls of the dam or break, we see the ridge line and the shallow ellipse of another cluster of glittering lights below—the JPL campus. She reverses the setting and the aesthetic in the quasi-minimalist, intensely concentrated Devil’s Gate (2014/2019), where she turns three regular perforations in the dam wall into frames for a kind of stop-action trace of the moving figure. We can ‘read’ the image several ways. The softly fluttering ribbons of light seem to collide in the center frame sending off a starburst of arcs and loops. In the meantime, the mass of blackened wall set against the sapphire blue of the sky above it (itself striated with power lines) elicits a kind of Ellsworth Kelly elegance.

The career of the body (or as Halloran might put it, the ‘body that sees’) in space is a through-line in Halloran’s work; and she is no less conscious of the relations between moving bodies that characterize the physical actuality of our environment. So it almost seems inevitable that Halloran would at some point take to the sky (if not deep space) to explore these relations—and the traces bodies such as hers/ours have made. In Double Horizon, Halloran pilots her own plane, and the ‘three-frame stop-action’ of Devil’s Gate gives way to a three-channel video projection in which Halloran herself, seated in the cockpit of her plane, frequently occupies one of the frames. If Halloran cannot necessarily maneuver the plane quite as adroitly or stylishly as her skateboard, she can nevertheless show us something of her bisected consciousness as she navigates between the horizons of her flight path and what lies in her wake. In its four-camera photography, editing and digital manipulation it becomes a tri-sected landscape-performance of consciousness and place. It begins straightforwardly, almost conventionally, with Halloran’s plane taking off somewhere above the San Gabriel Valley veering over Hollywood, then moving outward through L.A.’s vast suburban wastelands, its beaches (as far as Catalina), and downtown; but then begins to fracture kaleidoscopically, as the plane finds its flying ghosts in shadows and birds, natural landmarks facing off their simulacra in human-engineered installations and developments, and the downtown skyline is flipped over to become downtown sky. At one point pieces of sky begin to converge in what might remind the viewer of one of the cyanotype tondos of heavenly bodies Halloran exhibited in a previous exhibition at the gallery. A reservoir (inevitable) becomes a prismatic jewel. ‘The projections start to converge on the viewer,’ (or something like that)—I began recalling bits of Ellen Page in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film, Inception.

The career of the body (or as Halloran might put it, the ‘body that sees’) in space is a through-line in Halloran’s work; and she is no less conscious of the relations between moving bodies that characterize the physical actuality of our environment. So it almost seems inevitable that Halloran would at some point take to the sky (if not deep space) to explore these relations—and the traces bodies such as hers/ours have made. In Double Horizon, Halloran pilots her own plane, and the ‘three-frame stop-action’ of Devil’s Gate gives way to a three-channel video projection in which Halloran herself, seated in the cockpit of her plane, frequently occupies one of the frames. If Halloran cannot necessarily maneuver the plane quite as adroitly or stylishly as her skateboard, she can nevertheless show us something of her bisected consciousness as she navigates between the horizons of her flight path and what lies in her wake. In its four-camera photography, editing and digital manipulation it becomes a tri-sected landscape-performance of consciousness and place. It begins straightforwardly, almost conventionally, with Halloran’s plane taking off somewhere above the San Gabriel Valley veering over Hollywood, then moving outward through L.A.’s vast suburban wastelands, its beaches (as far as Catalina), and downtown; but then begins to fracture kaleidoscopically, as the plane finds its flying ghosts in shadows and birds, natural landmarks facing off their simulacra in human-engineered installations and developments, and the downtown skyline is flipped over to become downtown sky. At one point pieces of sky begin to converge in what might remind the viewer of one of the cyanotype tondos of heavenly bodies Halloran exhibited in a previous exhibition at the gallery. A reservoir (inevitable) becomes a prismatic jewel. ‘The projections start to converge on the viewer,’ (or something like that)—I began recalling bits of Ellen Page in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film, Inception.

Then, too, there’s that other question Page (as Ariadne) asks in the Nolan film: “My question is what happens when you start messing with the physics of it all?”—a question Halloran poses on several levels through the course of this brilliant show.

0 Comments