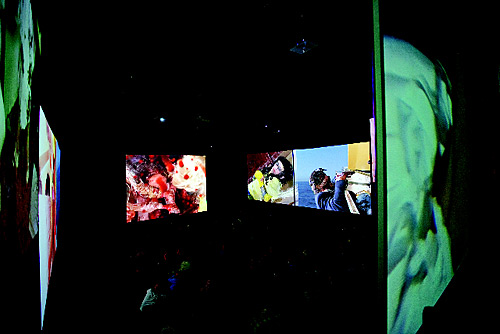

Pirates received its Los Angeles premiere at REDCAT recently: a visual and aural multi-screen feast/assault that covered all four walls of the theater. The audience, many of whom sat on the floor, were surrounded like the victims of the raid taking place onscreen(s). The only way out was through the exit door, which guilty-looking art lovers frequently resorted to, smiling awkwardly as they fled.Paul McCarthy, famed for his shit sculptures, chocolate butt plugs and other artistic inquiries that are lauded as forceful critiques of consumerism, has now plundered the pirate tradition in a style that is surely closer to the seafaring realities of yore than the Disneyland ride and movie franchise it cruelly parodies.As soon as the industrial-sized cans of Hershey’s chocolate syrup came crashing through the hatchway, the audience knew it was in for a McCarthy-style barrage of blood and shit on the high seas. Swollen-bellied, bulbous-nosed, giant-eared old salts squirted chocolate syrup from prosthetic phalluses, simulated masturbation with broom handles, sawed through noses and generally had a roaring good time. Blood was flying everywhere, pouring down the lens to a deafening soundtrack of drilling, screaming and obscene Yaaars and Aye-Ayes.

Upon any one of nine screens at any given moment one was greeted with such sights as a naked woman crawling around on a carpet in front of a ship-shaped bar, caressing herself with pained, imploring looks; a man with a freshly hacked-off leg being ridden by a droopy-nosed harpy in a blood-soaked scullery maid’s outfit; and the figure of the pegboy, famed in maritime lore, evoked by a sporty nautical gent in blazer and seaman’s cap who danced around a bottle of Morgan’s rum before frigging himself on a giant peg (the pegboy was a selected crew member who was obliged to keep his anus dilated in this fashion for the pleasure of his shipmates while on long voyages). Somewhere in there a parody of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was apparently being played out, but it was impossible to keep up with all the references. The playfully tasteless mayhem continued for the standard theatrical 90 minutes, descending eventually into such popular piratical pursuits as cannibalism and torture (despite their cartoonishness, the bone-splintering amputation scenes were not for the squeamish).

It was fun to watch and it was obviously fun to make. To those of us unfortunates unable to draw upon an arsenal of critical theory in order to make the work appropriately rigorous, it was an old-fashioned bloodbath, an unabashed extension of the work of Herschell Gordon Lewis. This was cinema divested of such tiresome niceties as plot, character and dialogue, focusing exclusively on filth and gore, which, after all, is what most people go to the movies for. Visually stimulating, it therefore possessed value as entertainment. Only the crowd, strangely, did not seem entertained.

One would think that such a scathingly visceral overload might provoke some sort of reaction. But looking around the audience — whose expressions it was easy to gauge as everybody was obliged to continually twist and crane around in order to view the different screens — there was no laughter, no smiling. It looked like an uncomfortable experience for many, especially those who were on dates. Most people wore looks of tolerant amusement or puzzled seriousness. Resistant to the notion of mere entertainment, they seemed unsure of how they were supposed to react. They knew they were supposed to like it because it was supposed to be art, but appeared uncertain about whether many of the depicted acts could be morally sanctioned.

It seems a shame that a work of such crazed vitality should be the exclusive province of an audience that insists upon extracting or impressing meaning upon it, when the multiplex crowd would surely get a lot more pleasure out of it. The average moviegoer, quite forgivably, might fail to interpret the sordid merrymaking on view as a critique of the Hollywood dream factory and a metaphor for the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In years to come, Caribbean Pirates will probably serve as a worthy corollary to these times, but the only people who are likely to make that connection now are the chosen art house set, who made up their minds about Abu Ghraib long before McCarthy went to such excessive lengths to tell them what they already knew.

This is a work that lends itself generously to the possibilities of audience participation. It isn’t being marketed properly. Why not release it to a less discerning audience: one that would actually enjoy it? ■