Let me talk. How often have I had to say that? Or wanted to say that? Or conversely, put it back to an interlocutor—‘no, go ahead—you talk; I want to hear what you have to say.’ Or in yet another mood or set of conditions, thought to myself, ‘let me hear this out.’ Sometimes—more often than not—the problem, the information vacuum, or alternatively the ‘noise’, is in what remains unsaid, the predicate to the subject at hand, the underlying assumptions and conditions to what is under discussion, or its unspoken (and frequently uncomfortable) implications.

Like a number of other shows over the last six months to a year or so, this was a show originally conceived partially in response to the conditions of the four or five years preceding late January of 2021, but delayed because of the SARS-CoV2 pandemic of the last couple of years (though to some extent, the “hateful environment” that curators Ada Pullini Brown and Jill Sykes reference as both conditioning and provoking artists represented here was undoubtedly amplified and aggravated by the often capricious tensions and isolations induced over the course of the virus variant surges).

Writing about art—or for that matter technology, politics, urban social or cultural issues—often seems more about writing about what I want to know rather than something I already know or can readily describe. But the scope of this show is almost beyond what any single artist—or even 24 of them—could hope to somehow encapsulate or apostrophize in one or two works, or conceivably even a substantial body of work. The multiple helices of global socio-political and power divides are on the order of the kind of ‘hyper-object’ some people refer to with respect to global climate change, artificial intelligence, augmented or parallel realities and parallel universes. In other words, the artists here are effectively in the same place, trying to ‘geo-locate’ something that can scarcely be described much less fully comprehended. “And yet,” as art historian and critic Betty Ann Brown writes in her foreword summary, “artists, who allow their life experiences to flow through them and emerge in aesthetic form, continue to create works that ‘speak’ to the volatile issues of contemporary culture.”

Catherine Ruane, “General Pico” (2021)

This is merely supplemental to the review that Genie Davis already wrote in this space and not intended as a further overview, but simply a response to some of the extraordinary works channeling and responding to that ‘volatility’. By far the greatest source of such volatility (even today, as humans find themselves in a battle for their freedom from authoritarianism and repression) is the destruction of the biosphere wrought by human predations across the entire planet. The best work here, both large and small, had a (not necessarily literal) immersive quality. It was appropriate, I thought, that viewers should be greeted by Catherine Ruane’s General Pico, which framed and seemed to almost spill into the entry into the main exhibition space. The subject tree—an ancient sycamore that has stood on the Irvine Ranch for centuries—has its own dark back-story of intra-species violence. Ruane explains in the exhibition’s accompanying text that the tree was used for multiple lynchings, including a pair by one of its principal ranchers, General Pico. Ruane’s beautiful articulation of light and shadow in the looming section of the tree’s bough eloquently set the mood for the exhibition.

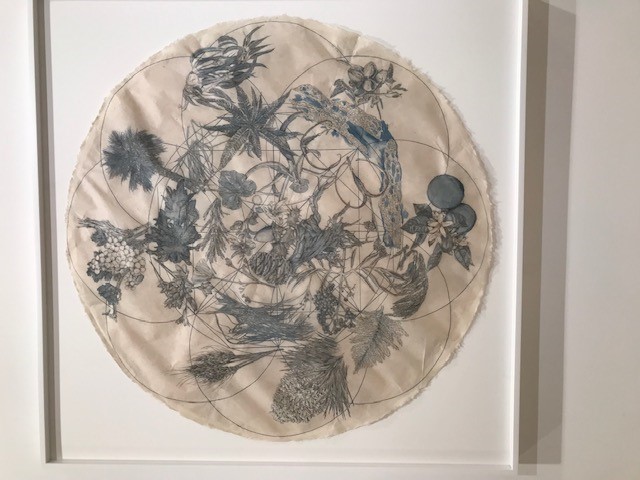

A sense of entrance, exit, and overhang permeates the exhibition—distance, departure, loss, migration loom in the shadows of much of the work here. Walk-through can seem to foreshadow a kind of walkabout in an almost aboriginal sense. (We’re in transition here and wherever we’re going near or far, we’re not all likely to survive.) Miyo Stevens-Gandara brilliantly uses the notion of the Japanese noren or doorway hanging (that many of us are familiar with in Japanese restaurants and noodle shops) to convey the sense of transitions from the micro-biome to the macro-cultural (in indigo-dyed fabric and embroidery). Then, in Dismal Cycle: California Flora, deliberately invoking a parallel to the ‘dismal science’ of human economic life, she traces on kozo paper a kind of devolution of California plant life—from its oldest native plant life at the center spiraling out to more recent native, non-native and the monocultured species of agriculture at its circumference—a delicate and poetic ‘bead’ on the strikingly indelicate impact of human life on plants. (Stevens-Gandara—with the help of Self-Help Graphics and 26 other artists—has also curated a fantastic portfolio of prints for the show, Utopia/Dystopia, that’s worth more than a black-jack flip.)

A sense of entrance, exit, and overhang permeates the exhibition—distance, departure, loss, migration loom in the shadows of much of the work here. Walk-through can seem to foreshadow a kind of walkabout in an almost aboriginal sense. (We’re in transition here and wherever we’re going near or far, we’re not all likely to survive.) Miyo Stevens-Gandara brilliantly uses the notion of the Japanese noren or doorway hanging (that many of us are familiar with in Japanese restaurants and noodle shops) to convey the sense of transitions from the micro-biome to the macro-cultural (in indigo-dyed fabric and embroidery). Then, in Dismal Cycle: California Flora, deliberately invoking a parallel to the ‘dismal science’ of human economic life, she traces on kozo paper a kind of devolution of California plant life—from its oldest native plant life at the center spiraling out to more recent native, non-native and the monocultured species of agriculture at its circumference—a delicate and poetic ‘bead’ on the strikingly indelicate impact of human life on plants. (Stevens-Gandara—with the help of Self-Help Graphics and 26 other artists—has also curated a fantastic portfolio of prints for the show, Utopia/Dystopia, that’s worth more than a black-jack flip.)

Sierra Pecheur, “Ghost Heart (humanity)” (2019)

Some of the most striking works on view were also the smallest—Sierra Pecheur’s porcelain Ghost Hearts, more or less human-scaled and modeled hearts, but variously distorted, mutated or simply scarred; or in one instance, Ghost Heart (humanity) nestling (or clotted with) other human hearts in progress. No need to wait for plaques and platelets to congeal into deadly obstructive blockages and emboli; mere procreation should do the trick. Pecheur characterizes the work (part of a series, related in turn to other interconnected bodies of work) as “a grieving,” which, absent color, seemingly drained of life force, makes sense. But she adds that the work is also partially “warning”—which makes even more sense. It is a sophisticated, highly efficient, yet vulnerable engine, destined to fail—its maturation synchronous with its scarring. The show has us looking at memory here on many levels—muscle memory, earth or geological memory.

Mark Steven Greenfield, “Incognegro” series (2005-07)

There is every kind of scarring, ‘inflammation’, and degradation available here—some of it left in our wake as residue, some of it impossible to really leave behind—carried forward generationally in one form or another and for all we know surviving the planet’s obliteration. (Can we hope those dark stars and black holes dispose of any of this in the astral domain?) With his Incognegro series (2005-07), Mark Steven Greenfield touches on a specific specimen of this dark cultural/historical stain in humanity’s scarrifying trajectory across the planet—specifically white actors and vaudevillians (or conceivably ‘costumed’ non-professionals) in blackface. Greenfield arranged his lozenge-framed lenticular images (blackface/blancface) into a similarly lozenged configuration of four, which heightened the tension in the dubious convergence of ‘double identities’—which aren’t really identities at all, or even masks. (It’s truly astonishing to realize how long ‘blackface’ minstrelsy and other entertainment forms persisted in Euro-American culture.) The shock lies not simply in the degradation of the ‘other’, but negation of the underlying identity—really identity altogether. It’s the dirtiest of psychological crimes at the diseased roots of paranoid authoritarian strains in American social and political culture.

Margaret Griffith, “101280” (2021)

Margaret Griffith’s magnificent melting ‘gates’, 15th, 17th, and Pennsylvania (2017)—as in Pennsylvania Avenue, or more specifically, the White House gates, in Washington, D.C., provided a signature ‘melt-down’ moment for the exhibition, exemplifying the illusion of entrance and exit, of barrier, (and as she puts it in her statement, “permanence”). Its political dimension can hardly be magnified—doubly ironic, given the ‘melt-down’ level confrontation between riot police and a throng of protestors in Lafayette Square three or so years later as the former president (already pressing to invoke the Insurrection Act!) was escorted to St. John’s Church for a photo-sitting that fell far short of its promotional objective. Griffith’s spiral of chain link fencing—in paper, 101280 was no less show-stopping, evoking the sanitized and stateless hell of migration.

Cynthia Minet, “Seconds to Last” (2021)

Cynthia Minet’s work has long concerned notions of passage, transition (and their mechanics), migration, duration (or even shifting notions of duration), the environment beyond the human domain, and throughout, significantly, sustainability. (I may be exaggerating, but almost all of her three-dimensional work has been made with recycled materials—frequently recycled/discarded plastic fragments, mechanical, and color and lighting elements.) Two of her 2016 gouache/watercolor Spoonbills—part of her Migrations series—were on view here. But above all, Minet’s work is alive to the pure drama of animal movement, from the avian to the canine; and here she filled an installation space with one of her most dramatic constructions to date, Seconds to Last (2021)—a single large rhinoceros (a Northern White, to be specific) constructed from beautifully articulated fragments of recycled camping tents, inflated, and lit from within by sequenced LEDs, which enhanced the multicolored fabric panels—the head and horn a pale amethyst color, the shoulders in buff, gray and chartreuse panels, the mid-sections in amber and umber, and rear in deeper green and umber. Unlike some of her previous motile animal figures, this rhinoceros was not specifically in motion. Then, too, there was only so far it could go—literally and figuratively: it’s not merely threatened, the species is nearly extinct; there are only two surviving Northern Whites on the planet. The effect, as the light moved through the gorgeous beast, modulating, and finally dimming to grayed-out, blacked-out darkness, was of a quiet, labored respiration fading to the last breath. Nothing further needed to be said—then or now (missiles fly and bombs fall on the other longitudinal hemisphere as I write this). It is a kind of conjuring by re-animation and witnessing as meditation. Just let me listen.

Let Me Talk — co-curated by Ada Pullini Brown & Jill Sykes — The Brand Library & Art Center – through March 19, 2022 (Including work by: Margaret Alarcon, Dawn Arrowsmith, Ada Ppullini Brown, Lavialle Campbell, Eileen Cowin, Bibi Davidson, Bianca Dorso, Mark Steven Greenfield, Margaret Griffith, Dean Larson, Laura Larson, Cynthia Minet, Sierra Pecheur, Serena Potter, Catherine Ruane, Shizu Saldamando, Leigh Salgado, Barbara T. Smith, Miyo Stevens-Gandara, Theodore Svenningsen, Jill Sykes, J. Michael Walker, Cathy Weiss, Nancy Youdelman, Self Help Graphics) The Brand Library & Art Center – 1601 West Mountain Street, Glendale 91201