The paintings of Lenz Geerk are unprepossessing and quietly sublime, his figures poised inside singular moments of divine inscrutability as they consider the world around them, whether it be a dying flower or the pointed edge of a table. This sense of veiled mystery could be said to denote a distinctly German sensibility as there are obvious connections with artists like Ludwig Kirchner and Rudolf Schlichter, yet it is Geerk’s celebration of the mundane—the passing moment, an ominous glance that lingers in place of a smile—that makes his work so memorable. There is a sense of timelessness at work here, as though each figure were cradled inside an ever-expanding universe of nothingness—a strange and incontrovertible paradise wherein a kitchen table becomes a makeshift stage onto which Geerk’s human narratives play out.

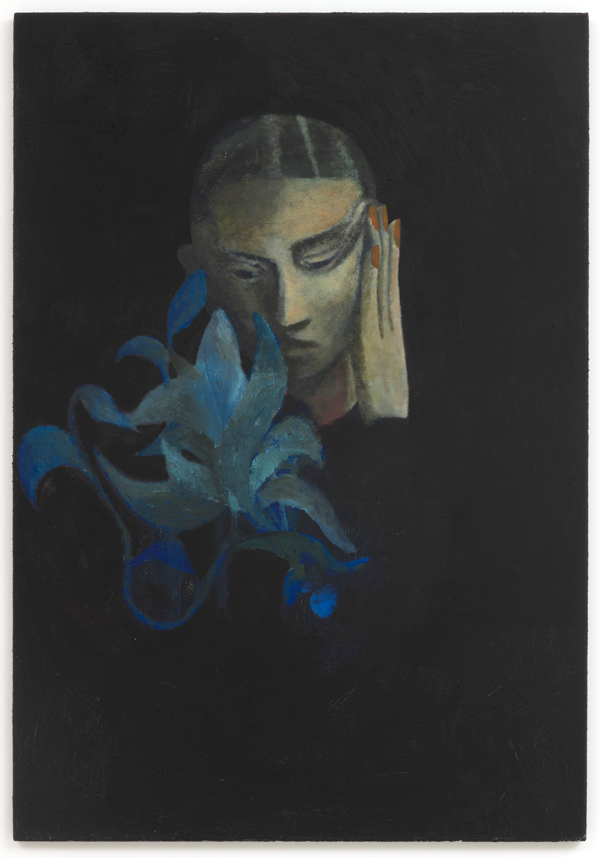

Boy with Blueberry, 2017, Acrylic on wool, 57.1 x 39.38 in, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, Photo Robert Wedemeyer

Born in Switzerland, Lenz Geerk lives and works in Dusseldorf. This makes sense when considering the opaque and sometimes unsettling content of his paintings. The hard-edged lines and darkly mutable atmosphere that is Germany fills his work, creating a sense of wonder but also a palpable sense of despair in the viewer.

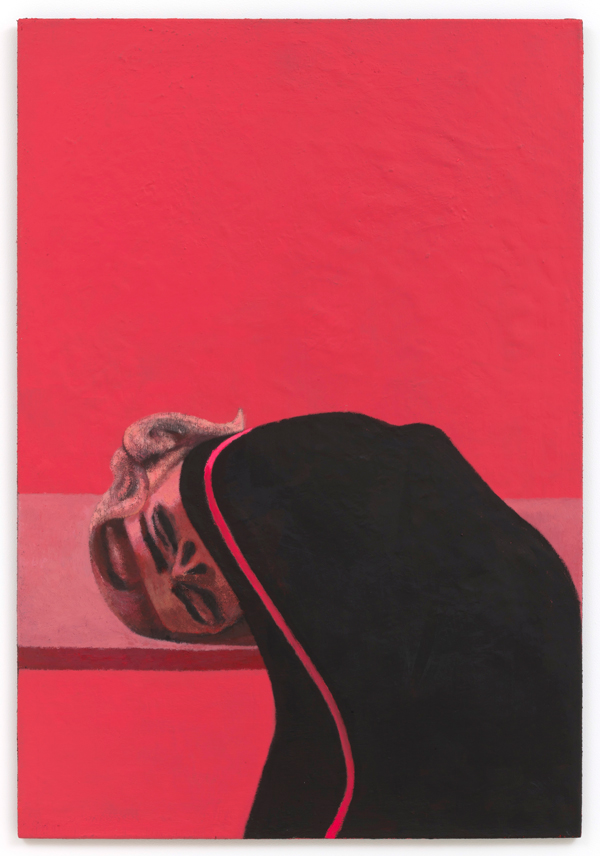

Geerk engages oppositional tensions within each of these paintings including hard versus soft and achromatic versus color, etc. Even the surfaces he paints on (acrylic on wool) reflect this sensibility as they retain the haziness and mutability of the materials he uses. This is most evident in the “table paintings,” where the softness of human flesh appears strangely at odds with the harsh reality of the table’s slick surfaces. In most of these images, Geerk’s figures appear to have no agency—their bodies limp and lifeless, draped as though they too were inanimate objects. This privileging of the single figure as the central object within the frame, and poised inside a moment of indecision or impossible self-reflection, is reminiscent of the work of Balthus. Like Balthus, the figures that populate Geerk’s paintings are as removed and disconnected from themselves as they are from the surrounding space, allowing the interiors they occupy to become passive characters within an already psychologically charged visual narrative. This is most evident in works like Table Portrait V in which the central figure’s face is half obscured, her eyes closed, her head twisted into her body at an oddly disconcerting angle as though she was somehow “placed” there against her will or without her knowledge. The table she rests on appears to be floating weightless in space, adding to the feeling of displacement; but what makes this painting so powerfully resonant is the single orange line that runs the length of the woman’s arm, further grounding her into the space and connecting her body to the orange background.

Table Portrait V, 2018, Acrylic on wool, 57.1 x 39.38 in, Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, Photo Robert Wedemeyer

Again, Geerk utilizes a single gesture to create an entire narrative. Who is this young woman? Is she dead or alive? Is she sleeping or completely overwhelmed with sadness? Perhaps none of these narratives apply here and she is simply—like the table she rests on—inertly occupying space and time. In practically all of the paintings in this series, the central figure is a woman who is seen as passive and completely unaware. In every case, the woman’s eyes are closed and her head appears to be resting on a blank surface wherein she becomes more an object to be studied and considered than representative of a living being. In essence, these women become still lifes, the subtle curves of their bodies reminiscent of Giorgio Morandi’s elegantly luminous paintings of sea shells, trees and vessels.

This same sense of displacement is repeated in other works. In Boy with Blueberry (2017), a young man is seen shrouded in darkness; the only other verifiable object being a small blue flowering plant into which he gazes. In keeping with the starkly reductive table paintings, the central figure is also oddly disfigured, his left hand pushing back the skin around his eyes. There is a discernible sense of longing at work here and the fact that the boy is wearing red nail polish also adds an element of mystery and tension. One can’t help but wonder how and why this young boy came to such intense focus on this darkly blooming creature.

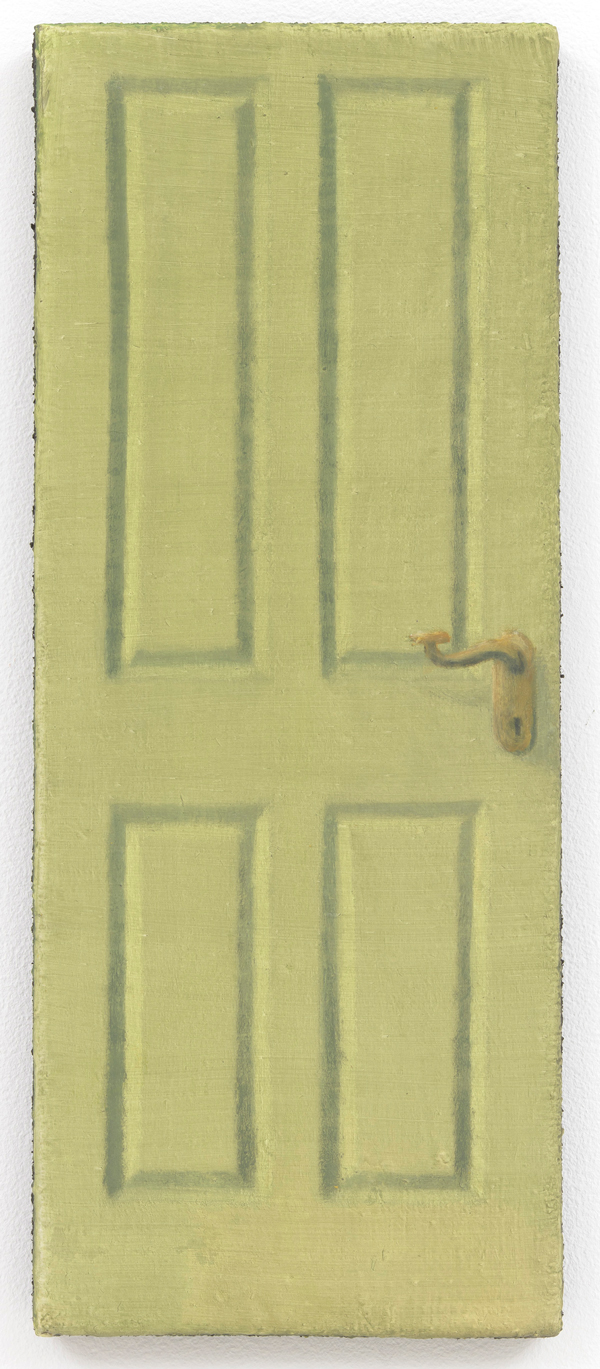

Green Door, 2018, Acrylic on wool, 19.7 x 7.9 in,

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, Photo Robert Wedemeyer

Geerk’s single object studies are also closely aligned with the work of Vija Celmins, most notably her photorealistic drawings and paintings of natural environments and phenomena. As with Celmins’ best work, Geerk’s subjects are more than stand-ins for the “real thing” but signify a deeper self-scrutiny within the person who has created the work, and deeper still, an awareness and identification on the part of the person who is viewing it. Works like the strangely enigmatic Green Door operate on multiple levels, both literally and associatively, as the door is a symbol of both what is and what could be, yet the object itself is a mirage, a fakery, a metaphor for the possibility of human experience, wherein the fantasy falls short of reality.

Finally, these paintings challenge our ideas of what constitutes reality, opting instead to expand that definition, or shatter it entirely. It does not seem to matter where we are in space, only that the forces that brought us there—to the edge of despair or to an equally singular moment of ecstasy—continue to act upon us subliminally, like magic, without our knowledge.