Jack Brogan, the legendary arts fabricator, quietly died at home on Wednesday, September 14 at 3:30 PM. He was 92 years old. His long life was exemplary.

Born in Tennessee in 1930, Brogan came home after serving in the Korean War. He drove a truck until the unions shut him down. Then he hauled produce. He studied engineering “here and there.”

His entrepreneurial drive bought him a concrete plant that would pour blocks in the morning, steam-cure them over noon and load for delivery by five. He cast custom architectural parts, invented machinery to produce concrete pipes and made the concrete pads that sit under a phone booth for Southern Bell. Debilitating neck surgery demanded that Brogan sell his concrete interest and move to a warmer climate.

Brogan arrived in Los Angeles in 1958 where he opened a cabinet and furniture finishing shop. He built models and prototypes for Knoll. He solved production problems that the Eames brothers could not configure for Herman Miller.

As real estate was voraciously developed across the Southland, Brogan was fabricating models, designing lobbies, logos and ephemera for the developers.

In postwar California, the aerospace and automotive industries were leading the charge for new materials and high-tech manufacturing processes. The always curious Brogan never missed an innovation.

In the mid-’60s, Robert Irwin asked Lucius Hudson, the legendary stretcher-bar maker, for help with a concept of a large silver disc. Hudson sent the visionary artist down the block to Brogan’s shop in Venice.

Having a blast, Jack Brogan began to work with many artists. His knowledge of new materials and his “can-do” creativity became an inspiration and valued resource. Brogan held many hands. The artists may have seen the Light, but Brogan knew how to create the Space. The Tennessean did not coin the term “Finish Fetish,” but everyone knew that Brogan was fetishistic about the perfection of the finish.

Christopher Knight, the LA Times art critic reminds us, “In the 1960s, fabricators working for artists were uncommon, while now the collaboration happens routinely.”

Was Jack Brogan an artist’s assistant, a fabricator, a collaborator or an artist? The opinion depends upon whom you are talking. Back then, the rowdy artists from Venice, all surfers, daredevils and motorcycle racers, were chest-thumpers. Many times, Brogan was never invited to an opening, lest the cat leap out of the bag.

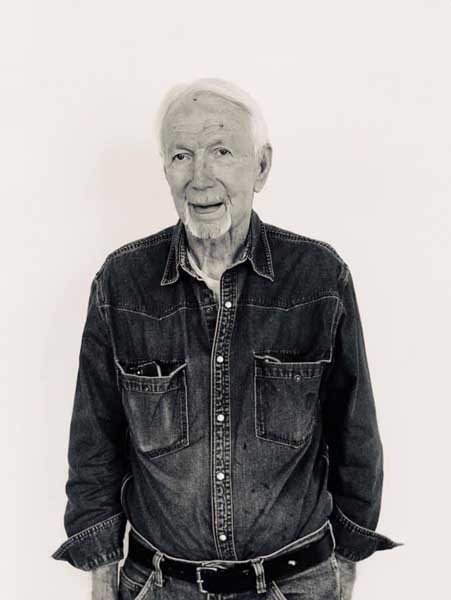

Photo by Eric Minh Swenson

Tall and lanky, Jack Brogan was always impeccably dressed and was meticulous in his appearance. Mark Schmidt, a Minimalist artist of the Custom Culture school, was doing some work at Jack’s house and recalls, “I used to watch Jack every morning wash, clean and polish his boots. Of course, he had all of the proper equipment.” The Tennessean was a Southern gentleman who took great pride in himself and his work. Schmidt says, “Jack had thoughtful manners. Gentility. His etiquette was impeccable. He liked to do things for people. So kind. That was Jack.”

Brogan was a fun guy with a boyish sense of humor. Schmidt, who considered Brogan as a mentor says, “He was the first guy to make a joke. He liked to laugh. Jack and his pal, the artist Cosimo Cavallaro, were like a Laurel and Hardy comedy team.”

As a gentleman, Jack was never afraid to come to the aid of a lady. There is a wild tale, after a James Turrell opening at the Stedelijk Museum, when a rude German gallerist was harassing a woman. Jack, politely and to no avail, made several recommendations for better behavior. Pushed to his limit, Brogan picked up the gallerist and tossed him in the Dutch canal. LA artist John Eden tells this story of gallantry and humor in great detail.

Brogan was a foodie. Schmidt tells us that he would carry a small spice shaker everywhere he went, filled with his ten herbs and spices. Jack would spread his dream flavors on everything he ate at a fast-food drive-thru, an off-the-alley Mexican café or a Beverly Hills brasserie. Case in point, artist Jan Taylor gives us the recipe for Jack Brogan Chili, which takes only 48 hours and 20 minutes to prepare.

L-R: Doug Edge, Jack and his wife, Edith Baumann; photo by Mark Schmidt.

Second to fine cuisine, Brogan loved fast cars. He was a NASCAR fan. Arriving in Southern California in 1958, Brogan found himself in the nucleus of automotive innovation. From speed to finishes, he was very involved in the industry, from paint producers to rod shops to pinstripers.

As his reputation grew and museum handlers continued to drop art objects, Brogan became busier than ever, repairing historically significant art, fabricating new works and freely dispensing advice. Brogan’s client list reads like a Who’s Who of the Blue Chip set. Irwin. Bell. Burden. Benglis. Gehry. Kaufmann. Pashgian. Turrell. McCracken. Moses. Valentine. And so many more.

Jack was a personal friend of mine and I asked him once, “What is your fondest accomplishment?” The answer defines the man. He was thoughtful and replied slowly, savoring the two words, “Irwin’s Prisms.” Robert Irwin’s original piece was four feet tall, but soon grew to sixteen. To create the new height, Brogan had to devise a method to join the clear acrylic pieces and hide the seam. Mortals would fail; Brogan triumphed. The connection is invisible. Most significantly, the joint proved stronger than the casting in a series of stress tests. Like an alchemist with a secret, Brogan smiled silently, rather than divulging the composition of his chemical creation.

Should anyone come close to Brogan’s creativity and knowledge, it would be artist Eric Johnson, a fabricator who created for Craig Kauffman and Tony DeLap. “It’s not only his secrets that are lost,” says Johnson, “it’s his analytical compounding and his circumstantial creativity. You have to remember: Every project is a new challenge.”

Brogan was a lone individual who became an institution. He was the magician who never divulged a secret. Over the last decade, many an artist and curator have wrung their hands, fearing a future without Jack, debating the many issues of succession, process and material. Brogan was an original. There has been no heir apparent. There is no successor. Careful now, don’t drop that Irwin!

Jack had many passions with elaborate cowboy boots being one of them. You can find a photograph of a stellar pair in the essay “The Alchemist: A Profile of Jack Brogan” by Lawrence Weschler, featured in the Brooklyn Rail. The subtitle says so much to the man’s character, “He is thoroughly sure of his expertise and his value. He is very much his own man.” Weschler’s detailed and compelling article is highly recommended.

Jack Brogan is survived by his longtime spouse, painter Edith Baumann, and several children.

GORDY GRUNDY is an artist and arts writer. He is the editor-in-chief of Art Report Today.com