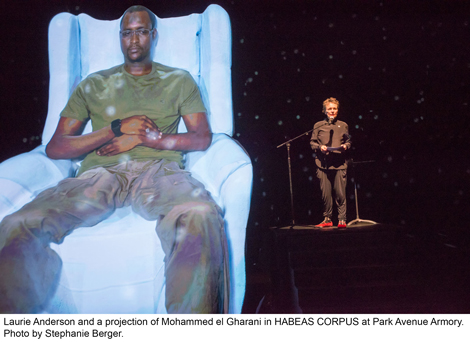

Laurie Anderson fairly disappeared in the gaping vastness of the darkened Park Avenue Armory. Standing, violin in hand, next to a Lincoln Memorial–sized plaster sculpture of an armchair, she told the story of Mohammed el Gharani.

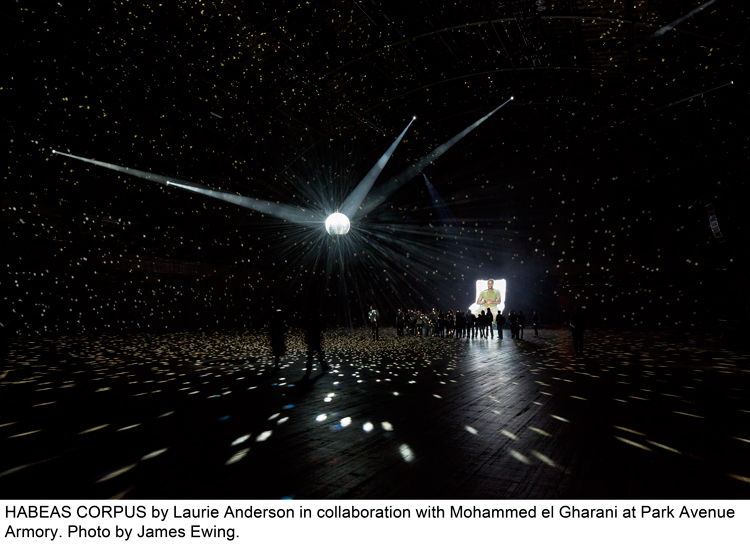

El Gharani—or rather his shimmering likeness, beamed live from West Africa for seven hours on each of three consecutive days in October—gazed over the thousand or so people sitting on the floorboards of the gargantuan drill hall as part of “Habeas Corpus,” Anderson’s New York performance on freedom, erasure and justice. As the audience milled about in the darkness, collaborators walked around the hall improvising on electronically distorted violins and performing parts of Feedback, a sound work by Lou Reed. Periodically the livestream would be interrupted by prerecorded segments in which the sitting man talked about his imprisonment in Guantanamo.

El Gharani, originally from Chad, spoke about being abducted by special forces, about being subjected to “enhanced interrogations,” and flown hooded by secret flight to Guantanamo by U.S. authorities who accused him of being an agent of al-Qaeda. He spoke of hunger strikes and forced feedings. When he spoke of Shaker Aamer, a fellow prisoner who took him under his wing and organized the prisoner resistance, and about the guilt he felt in leaving him behind, he often stopped and quietly cried.

For eight years, the now 28-year-old was tortured and interrogated in the Cuban prison camp. Then, almost as inexplicably as he had been captured, he was released for lack of evidence and—by inscrutable Kafkian fiat—sprung from the American gulag and sent back into the world. He was never charged nor given an apology but he was barred in perpetuity from entering the U.S., as are all ex-Guantanamo detainees.

“Habeas Corpus” was Anderson’s way to virtually “smuggle” him into the country that imprisoned and banished him, to “produce the body”—the legal meaning of the Latin habeas corpus—and confront our collective denial with his undeniable presence. Beaming the monumental image of one of the men who were physically removed to extrajudicial prisons and thus morally removed from our consciences back into Manhattan was also a monument to our guilt and to American perdition: a live transmission to the dark sites of our collective soul.

Anderson has experimented with the idea in previous works that beamed jailed prisoners into galleries (from Milan’s San Vittore jail for instance). “Habeas Corpus” is probably Anderson’s most overtly political work to date. The simple act of returning a voice and a likeness to one who had so violently been deprived of them—of re-appearing a disappeared—rendered almost superfluous the quotes on due process by Jefferson and Hamilton that hung at the entrance of the hall. The message was political, but it was effective mainly because of the intimacy of the encounter with el Gharani’s 3D-like telepresence projected onto the armchair sculpture.

Intimacy, incidentally, is also the prevalent tone of Anderson’s first feature-length film, Heart of a Dog, which will show on HBO following its limited release on the specialty circuit in November. The film is a first-person voice-over meditation on life and loss whose ostensible protagonist is the artist’s faithful rat terrier, Lolabelle.

The dog’s biography is a pretext for a stream-of-consciousness perambulation through the author’s own life and her practice of meditation, contemplation and art. It’s a free-associative film essay reminiscent in some ways of those of her quasi-namesake Thom Andersen, like LA Plays Itself and last year’s The Thoughts We Once Had. But where those are scholarly musings mostly on semiotics and film, Anderson’s film blends observations on personal experience, loss, tai chi and Buddhist meditation, the artist’s relationship with her mother and the emerging post-9/11 surveillance state.

The presence of Anderson’s companion Lou Reed (who died two years ago) obviously hovers over a film so concerned with death and loss (he also appears in music and has a brief cameo). “Lou’s spirit is very much in the film and I especially wanted to pay tribute to his fierceness,” said Anderson, when the film premiered at the Venice Festival back in September. “We talked a lot together about the force of expressing things simply.”

“Habeas Corpus” definitely also subscribed to that idea. Taken together, the two works testify to a new urgency, almost an impatience, to Anderson’s recent work. And that is not a bad thing.