Why, exactly, is Laura Owens’ art so compelling? This is a question I’ve been asking myself since I was in art school. Elusiveness seems intrinsic to her work’s magic, which in my mind boils down to two intertwined notions: possibility and freedom. Owens’ eclectic art exudes the liberating idea—perhaps not quite true for most painters but inspiring nonetheless—that a serious painting can depict any subject; a successful painter’s name need not become synonymous with a “brand identity” of executing the same things over and over.

Manifesting her oeuvre’s playful diversity, the LA artist’s mid-career survey at MOCA features about sixty paintings from the mid-1990s to the present. Since Owens often executes sets of related paintings with a mind towards how they will occupy a given space, the exhibition is organized less by chronology than around groupings of works that variably coalesce and contrast, such as a 2015 installation where five freestanding paintings align to form her son’s short composition beginning with the text, “There was a cat and an alien.”

On entering the show, one encounters a huge untitled 2014 painting (all her paintings are untitled) of a cartoon depicting a rope-swinging boy and his dog beside this bathetic sentence: “When you come to the end of your rope, make a knot and hang on.” In a classic Owens maneuver, the potentially deadening silliness of image and sentiment is rescued by visual intrigue: real collaged additions and phony trompe l’oeil ablations alternately accentuate and negate the painting’s flatness. Cutouts and drop shadows suggest shallow spatiality beyond the image’s surface, confounding the viewer’s notions of how this painting is formed and what it is supposed to depict. Jejunity is shattered.

A subsequent room harbors well-known 2002 and 2003 paintings inspired by 19th-century French decorative landscape painting. From afar, these pastel scenes of woodland creatures resemble textiles one might find in the children’s section at Ikea. Yet Owens’ mark-making is so intricate, her strange spatiality so complex, that such cutesy paintings can’t be faulted for lack of excellence.

The show’s layout imparts a sense of vagarious exploration; you never know what you’ll discover around the next corner. There are clever installations, monumental abstractions and alphabet paintings. Certain canvases incorporate real buttons, loops of yarn or even bicycle wheels. In one long gallery, a salon-style bevy portrays many denizens of fancy, some of which are floral textiles, pirates, horses, tigers and medieval soldiers. Owens isn’t afraid to come across as silly, girlish, decorative or unfashionable, yet her quirkily wrought paintings generally succeed.

Her unorthodox decisions often seem calculated to provoke reactions or elicit interactions. Throughout the gallery, the edges of drab gray museum benches’ upholstered seats are embroidered, at irregular intervals, with tiny vibrant motifs such as fruits and hearts; these are so inconspicuous that few patrons will notice. A 663-page exhibition catalog is ingeniously designed as a scrapbook archiving Owens’ personal ephemera, correspondences, influences and friendships. No two catalog covers are the same in an edition of 8,000 screen-printed in her studio. Such gestures read as the work of a relational artist as well as a painter, particularly in light of her interactive projects with 356 Mission.

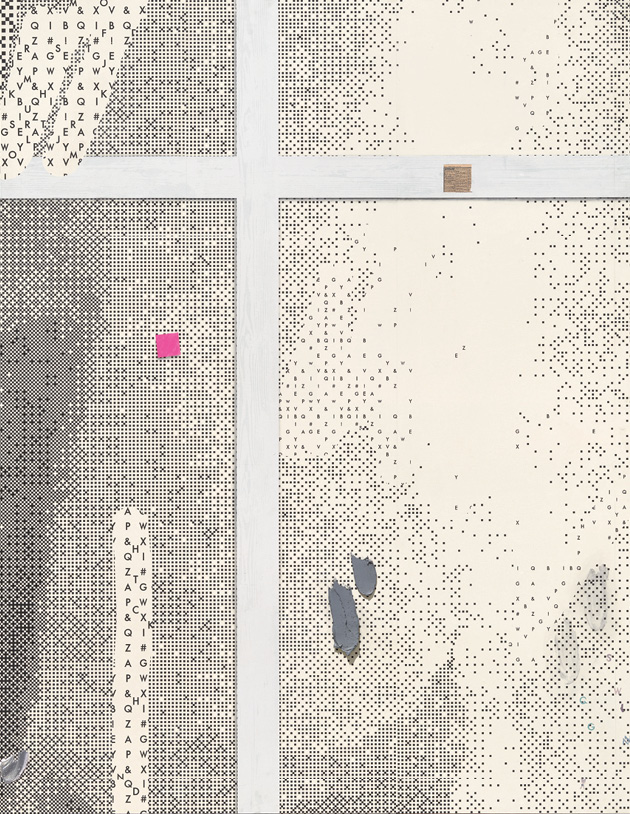

The survey culminates in several recent sets of abstractions condensing the spirit of her earlier work’s stylistic pluralism. Much of her painting since 2012 is defined by heterogeneous juxtapositions of loops, squiggles, screen-printed enlarged ephemera, and abstract forms that appear digitally collaged, with drop shadows imparting illusions of shallow depth. Evoking the feeling of zooming in on random parts of some inexplicable grandiose digital scheme, these colossal works appear as metaphors for painting itself, which, at its most fundamental, is about creating or isolating specific elements among potentially infinite iterations.

Constantly walking a tightrope of paradox, Owens employs deceptive simplicity to capture life’s complexity. Chaos belies calculation; cartoonishness gives way to existential seriousness. Her eclecticism imparts the sense of freedom inherent to painting; yet her glib veneers of casualness are generated by technical rigor.

A most amusing denouement overlooks the show’s egress: High above the threshold hang two neat rows of small kinetic paintings doubling as real timepieces. In typical Owens fashion, these whimsical painting-clocks are charged with deeper symbolism: the passage of time is literally registered by the movement of paintings supposed to be timeless and still. Sporting whimsical images such as cats and clowns, it almost feels as though these clocks are laughing at you. Would their mirth be directed at your mortality, your departure, or at the fact that you take them so seriously?