In two exhibitions spanning galleries some twenty-minutes apart depending on traffic, Larry Johnson presents his own work alongside that of two other gay artists of a certain age and a certain generation, who lived through the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and early ’90s—a traumatic period that not only shaped their lives but reshaped our society and culture. The works look to a common era, bending and queering found text and image. The work does not explain as much as it encourages contemplation and critical thinking.

At O-Town House, “Died and Gone to Hollywood,” an exhibition curated by Larry Johnson of the work of his friend and peer Joe Mama-Nitzberg, takes its name from a story about a gay man, hospitalized and dying of AIDS-related complications at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles. Sporadically conscious, he once woke up to a visit from Elizabeth Taylor. Later, when asked what it was like to awaken to an iconic movie star standing over his bed, the patient replied, “I thought I’d died and gone to Hollywood.” This act of snatching joy from the jaws of death sets the tone of an exhibition full of binaries.

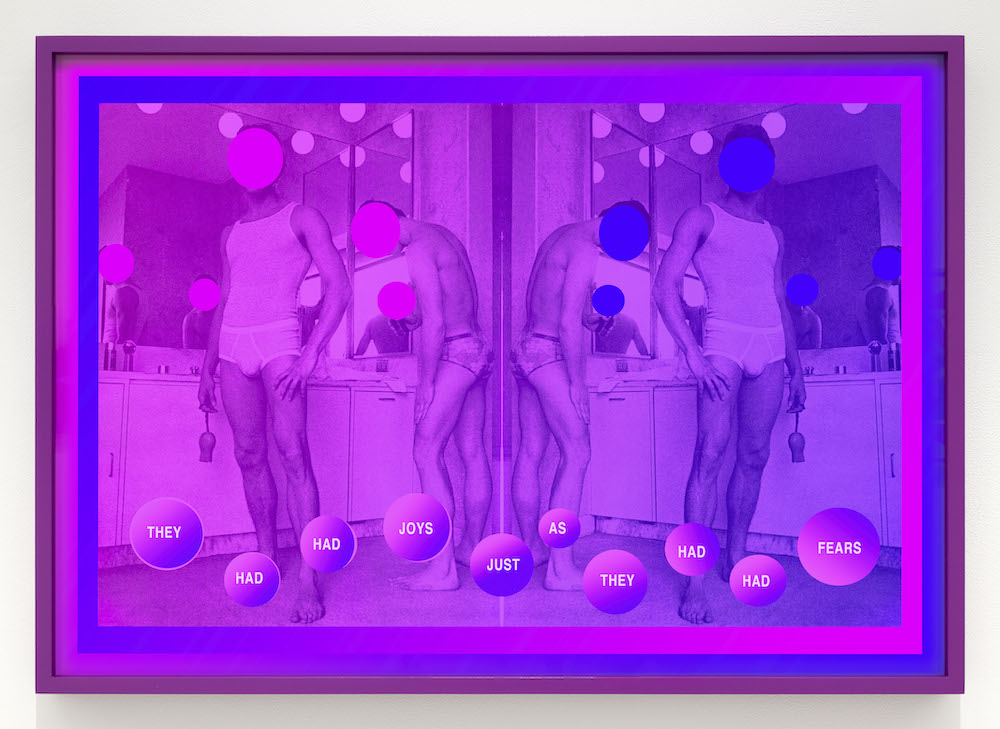

In Gay Semiotics: a photographic study of visual coding among homosexual men, theorist Hal Fischer writes, “In the gay semiotic the body is divided into sides, the left representing the aggressive, the right the passive. Any sign placed on the left side indicates that the wearer will always take an active role during sexual activity. Conversely, a sign on the right side of the body indicates passive behavior.” Mama-Nitzberg’s bifurcated compositions suggest the binaries of the AIDS epidemic: joy and pain, hope and fear, mass death and an outpouring creative output. They had had (2021) is a nod to John Baldessari’s use of dots; here they suggest bullet holes, obscuring the faces of two underwear-clad men. The composition is a split screen that flips the image horizontally, resulting in four figures. Pink dots obscure the men’s faces on the left side, while blue dots cover their faces on the right. The text superimposed on the left side of the image reads (in dots): “They had had joys …” The right side reads: “just as they had had fears”. While Fischer used the binary to articulate different means of signifying sexual preference, Nitzberg’s bifurcation defines the complexity of experience and emotions during the AIDS crisis.

Larry Johnson continues this theme of binaries via a visual conversation with Hedi El Kholti in a two-person show running concurrently at Reena Spaulings. Five of Johnson’s paste-up text works are exhibited alongside El Kholti’s collages. The press release describes the work and process in violent terms such as “surgery” and “dismemberment,” which makes the work seem less benign and more like savagery with an X-ACTO knife.

Yet for the suggestion of violence in these works, Johnson gets nostalgic with his subject matter and the return to the analog techniques he employed in the 1990s, adding to the retro vibe of these artworks. They all look back to queer history—especially queer Hollywood—whether it’s an obsession with true crime and murder houses in Untitled (Do Not Demo), 2024 or a double entendre referring to 1930s actress Kay Francis’s speech impediment that inspired the nickname “Wavishing Kay Fwancis” and also subtly references “gayspeak” in Untitled (Pasteup For Old Gay Men), 2024. While the work alludes to implicit signifiers of queerness, Untitled (Baskerville vs. Caslon) (2024) harnesses the explicit power of words via repetition, presenting the sentence TOM CRUISE DID NOT ATTEND GAY ARTIST PARTY WITH GAY COWBOY (an allusion to the numerous times the actor has denied being gay on record), first in Baskerville typeface and then in Caslon, resulting in a denial that uses the word “gay” four times, underscoring rather than refuting it.

In contrast to Johnson’s stark, text-only works is a series of colorful pop-culture-reference-filled collages by Moroccan-born semiotician Hedi El Kholti. The most imposing work, Untitled (Conquest), (2017) is a large-scale editioned image printed on vinyl that fills the entirety of a free-standing wall depicting a group of three men in swimsuits walking arm-and-arm into a hellscape, reminding me of the dualities of Mama-Nitzberg’s work at O-Town House. In a series of retooled book covers, the artist adds an image to a found travel guide to make a reference to his country of origin—also a legendary location for gay sex tourism—in Untitled (Fodor’s Morocco), (2013).

The binary code described by Hal Fisher was originally meant to enable gay men to function under a layer of secrecy. The AIDS epidemic was a period of exposure, forcing people to come out and become vocal and visible. Codes are still used for nostalgia and to reinforce group identity. The coded text and images found within the works by these three artists facilitates an ongoing conversation between the artists across two exhibitions about a shared experience that cannot be fully defined by historical accounts. The era needs to be felt, and the feeling is most effectively transmitted through art.