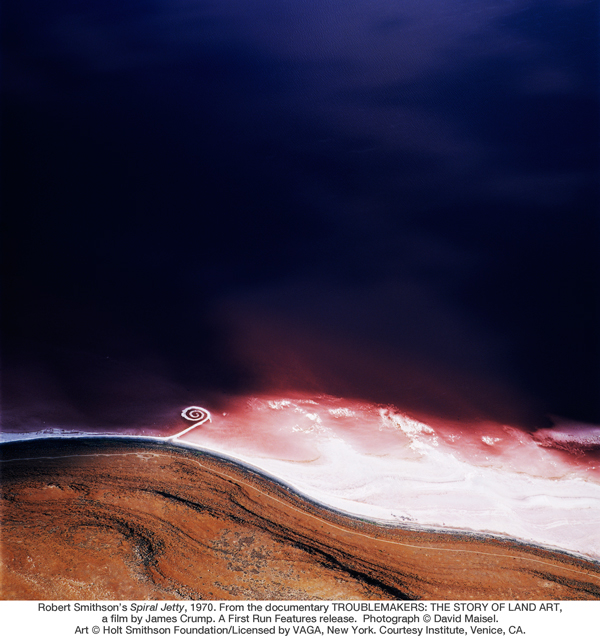

Land Art, also known as Earth Art, emerged in the period that was, with hindsight, clearly one of the most radical, innovative, experimental and groundbreaking periods in the history of art. The genre is part of a much wider trend that falls under the umbrella of conceptual art, and represented a shift away from art as a commodity and towards the dematerialization of the art object. Ironically, in these times in which art objects are being collected frenetically, the movement has finally received a proper documentary. Art historian, curator and filmmaker James Crump’s Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art is a long overdue tribute to this iconic era. Combining rare documentary footage from the epoch’s heyday in the 1960s and ’70s with contemporary interviews with artists who were active in that period (some key practitioners are now dead, including Robert Smithson, who died in a plane crash while working on Amarillo Ramp at the tender age of 35), the film manages to capture some of the wonder evoked by a visit to one of these sites.

The documentary is impressive because of its scholarly approach to the subject, carefully presenting it in the context of those tumultuous times, and clarifying the relationship between Earth Art and the myriad of conceptual activities that were happening concurrently. Testimonies from artists such as Minimalist Carl Andre and Conceptualists Vito Acconci and Lawrence Weiner along with filmed footage of the New York art scene help to capture the zeitgeist, one very different from that of today’s art world. Also of great interest are the sections devoted to Willoughby Sharp and Virginia Dwan, who both contributed to the movement by supporting it; Sharp through his short-lived, iconoclastic magazine Avalanche; and Dwan through her galleries in Los Angeles and New York, particularly through her direct financial support of Smithson and Michael Heizer (she was an heir to the 3M fortune). Recent interviews with Dwan are important additions to the Earth Art archive since she had such close associations with the principal artists.

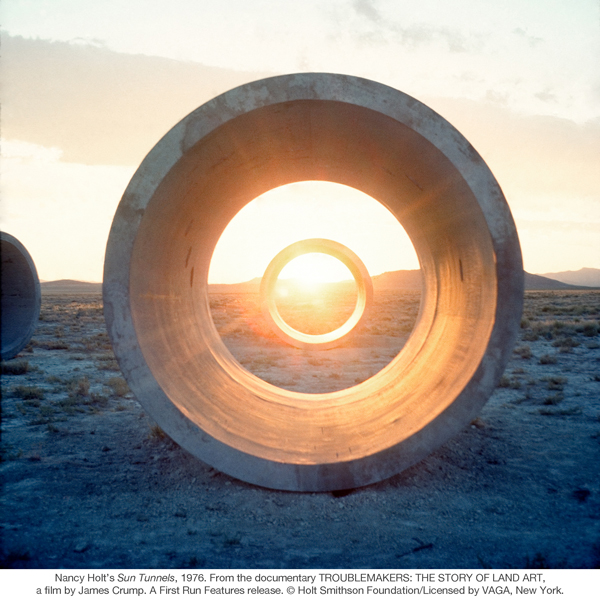

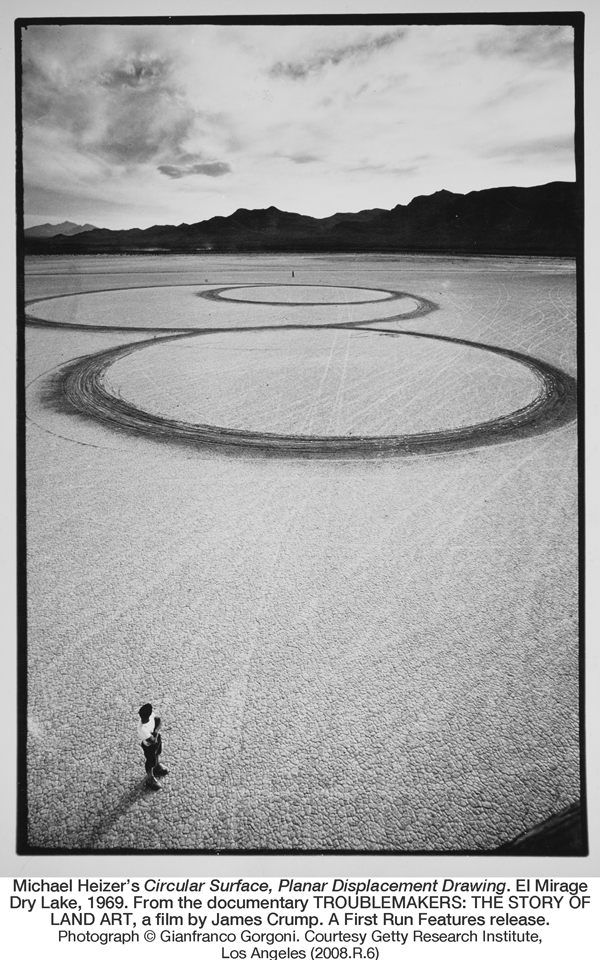

The film focuses primarily on Smithson, Heizer and Walter De Maria, the best-known artists for works in the landscape, but also includes Dennis Oppenheim, Charles Ross, Nancy Holt and James Turrell. Amongst the documentary’s highlights is the recent footage of Heizer’s Double Negative (1970), near Overton, Nevada. While keeping in mind that earth art can only be experienced firsthand (Heizer even forbade MOCA to exhibit photographs of his outdoor works for their “Ends of the Earth” exhibition in 2012), the extensive footage of this seminal work provides what must be the closest approximation yet to actually visiting such a site. Approaching the piece from every conceivable angle and from aerial views (the way these works are usually documented in photographs but seldom seen by most visitors) the film allows viewers to mentally assemble a complete gestalt of the work.

Although provocative, the film’s title, Troublemakers, does not really capture the true spirit of this singular kind of artwork. Yes, the artists were radically breaking away from the usual traditions of art-making and exhibiting, and many, such as Heizer, have reputations for being “difficult.” (Smithson is described as being “satanic” and having a “dark side.”) But the artists were clearly not out to create trouble for anyone, they simply had big ideas, huge ambitions and boundless energy. Far from creating trouble, the Earth Art experience puts us in touch with the divine, helping us to contemplate our place in the cosmos as we cling to the sphere we call planet Earth.

One of the overall concerns of this whole group of artists (which includes Conceptual and Performance artists) was to get away from the notion of artwork as a commodity. As Heizer remarked, “There are no values attached to something like this… it’s not worth anything; in fact, it’s an obligation.” Paradoxically, these works are only possible through the expenditure of vast sums of money, generally provided by wealthy visionaries like Virginia Dwan, Heiner Fredrick and the Dia Foundation. The end result is that we may experience them as works of art alone, unencumbered by associations of the staggering millions being paid currently for Rothkos, Bacons and Picassos. Can one ever look at a painting that sold for $140,000,000 without being influenced by that fact? Fortunately, Earthwork artists found a way to subvert this; the price we pay to experience them is not monetary but a journey akin to a religious pilgrimage. Troublemakers is an important historical document of a time when rather than embracing and manipulating the art market, artists actually chose to avoid it.