Your cart is currently empty!

Lancaster MOAH: : The Forest for the Trees

Although it was once relatively straightforward, the relationship between what we refer to as “Nature” and its inverted mirror-image “Culture” has become complicated and problematic. Indeed, the “default position” in the argument as to their reciprocal relationship is now defined by the idea that there is effectively no longer any such thing as “Nature” since, conceptually, any attempt at a definition must itself already be a cultural construct; while, physically, there is no longer any place on Earth where unadulterated Nature has not been overwritten by traces of human cultural activity. Some of the implications of this situation are explored by the artists represented in “The Forest for the Trees,” currently on view at the Museum of Art and History in Lancaster.

Although working from different conceptual premises, the idea that the world is something to be experienced in terms of movement through a fragmentary geography ties together the work of Timothy Robert Smith and Greg Rose. Smith’s multi-media, interactive installation takes the participant on a simulated rapid transit ride across a terrain that is defined by cultural activity; indeed, we are literally embedded in a constructed or a “cultured” world, out of which “Nature” erupts like an explosion of pigeons off a city street.

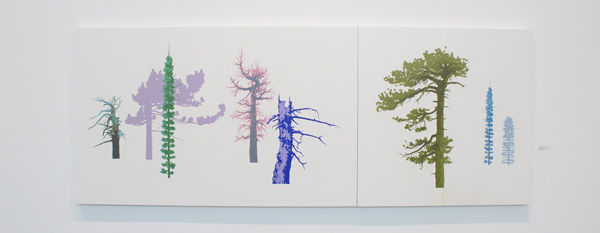

Rose, on the other hand, uses methods like mapping and “portraiture” to evoke the “historical” fiction constituted by his experience of individual trees over the course of repeated traverses of the San Gabriel Mountains. His chronicle of change and perceived interrelationships across an eight-year span can thus be seen as both an explicitly cultural artifact (like a novel) and a carefully crafted archive or (natural) history.

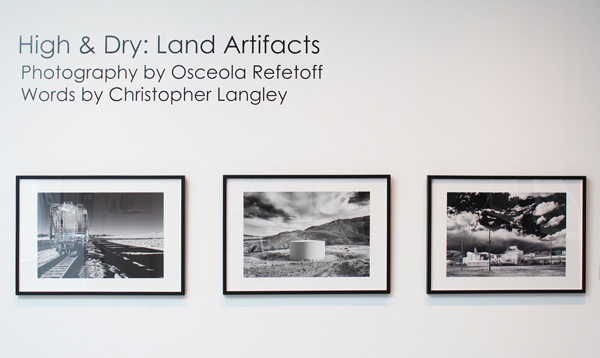

Although likewise radically dissimilar in appearance, both Constance Mallinson’s enormous and meticulously detailed still-life paintings and the augmented photo-installation from Osceola Refetoff and Chris Langley focus resonantly on the bits and pieces of material culture inevitably cast off on our transits across the natural world.

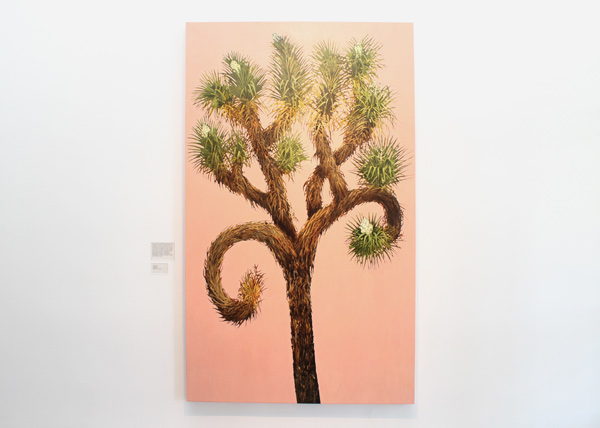

That leaves only Sant Khalsa’s Prana: Life with Trees, to my mind the high-point of the exhibition and in effect a mini-retrospective covering four decades of photographic and installation work, all bound up with the exploration of that deep Vedic energy binding us and those other living beings that we call “trees” together in a natural and spiritual eco-system. This is the hopeful heart of “Forest.” It is not without an acute awareness of the danger that we all face; but it also posits a strategy for transcending the anthropogenic “death of Nature” in favor of a new and reciprocally vivifying life within it.

Sant Khalsa, Constance Mallinson, Greg Rose, Timothy Robert Smith; High & Dry (Osceola Refetoff and Christopher Langely; Robert Dunahay, “The Forest for the Trees,” May 12 – July 15, 2018, at Lancaster Museum of Art and History, 665 W. Lancaster Boulevard, Lancaster, CA 93534. www.lancastermoah.org