With its third installment at the Hammer Museum, “Made in L.A.” has settled into its brand as a well-researched survey of current trends and practices in regional art. But there is never a “settling in” as far as expectations for a biennial, which raises the bar not only for curators and the artists involved, but also for those who experience it. Aiming to review the show, I spent one afternoon in the galleries and returned several times. Half of the projects inspired me; the other half left me confused.

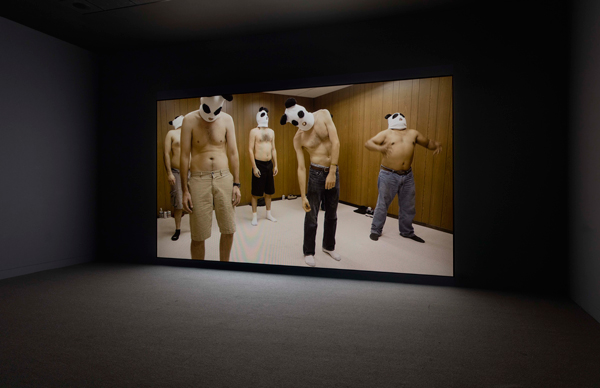

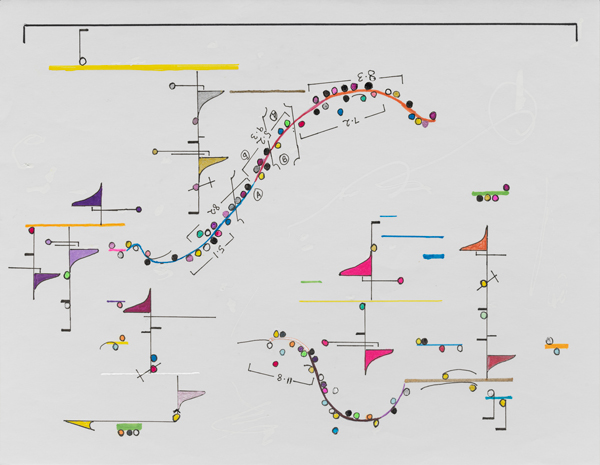

I gravitated to Kenneth Tam’s droll video about a group of men—total strangers—enlisted to participate in a social experiment of male bonding through absurd rituals; David R. Small’s “meta” project in which he took movie-set objects from The Ten Commandments (1923 version) literally unearthed from the film site and displayed them as ancient Egyptian artifacts; Wadada Leo Smith’s invented musical notation arranged within Kandinsky-like paintings on paper; Laida Lerxundi’s visually seductive films set in the Southern California landscape; Dena Yago’s veiled poetry as large letters tucked behind windows of translucent glass; Rafa Esparza’s labor-intensive installation of hand-made earthen bricks; Sterling Ruby’s found industrial tables covered in metal slag; Kenzi Shiokava’s rustic totems made of wood from his garden; and Adam Linder’s avant-garde production that rejects the emotionless perfection of modern dance.

Sterling Ruby, installation view, “Made in L.A. 2016, photo by Brian Forrest.

I had more difficulty with projects like cinematographer Arthur Jafa’s three-ring binder pages of clipped magazine images, which through juxtapositions present a personalized survey of black visual culture, and Labor Link TV’s videos of union activities revealing the plight of disenfranchised, mostly women and minority, workers. What these two examples have in common is that I wouldn’t have considered them art had I not experienced them in a gallery. Although Ruby’s found tables fit an art historical model of the “readymade,” Jafa’s found images, arranged in vitrines running the length of the gallery, fit a newer paradigm. Once I had read an interview in the exhibition catalog about Jafa’s practice of making the books as an outgrowth of his visual acuity as a filmmaker, I came to appreciate them. Labor Link TV’s amateur-quality footage of protests, strikes and arbitration hearings remained a tough sell. But led by artist and educator Fred Lonidier, who encouraged many of his UC San Diego students to participate, their activities could be comparable to Jafa’s when considered as an art practice.

Wadada Leo Smith, Vision, from Kosmic Music, n.d., one of four parts matted together, courtesy of the artist and Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago

Curious about my initial reaction to other projects that I felt were abstruse, I decided to conduct extensive research to see if knowing more could make a difference. I returned to the museum, checked things out online, and read the entire catalog. Clearly this is not a level of investment that most people put in. But it did generate what I’d call empathy. For example, learning about Lebanese artist Huguette Caland’s influence on the Venice Beach art scene as a kind of Gertrude Stein figure deepened my appreciation for her Paul Klee-like drawings and paintings. I had hoped that research would also turn around my reaction to Mark Verabioff’s cryptic installation of wall graphics. Why draw gang tears around the eyes of male rock stars, movie stars and politicians, whose portraits are arranged in rows? Without any explanation to help decode, I left it at that.

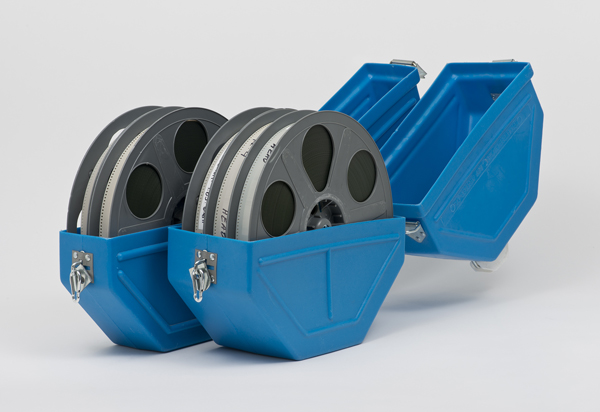

Margaret Honda, Cases and Reels for Color Correction, 2015, photo by Brian Forrest.

In contemporary art today, more often than not viewers are expected to educate themselves about artists and their work. There’s reward in that process, but it can also feel alienating. One issue I had with this show is that many works, at least on first encounter, felt needlessly inaccessible. This is often a challenge with performance and time-based works, a problem certainly not unique to this show. For example, seeing Margaret Honda’s 70mm and 35mm film reels and cases displayed on a pedestal made me wonder: “Is this it?” until I noticed the last sentence in the label about related film screenings. I was unable to attend, and could only rely on the catalog essay for any sense of her work.

My interest in Todd Gray’s restaging of a year-long performance in which he wore the clothes of his late friend Ray Manzarek of The Doors compelled me to search the Made in L.A. galleries, only to find a wall label. I was already aware of his performance through a concurrent exhibition at his LA gallery. I was disappointed to learn that the only way to experience his Hammer piece was to encounter the artist if he happened to be at the museum when I was. Letters that Gray wrote to Manzarek’s wife, which are part of the performance, are the best part of the piece. Reproduced in the Made in L.A. catalog and also read by Gray at an event I attended, they are well written, poignant and revelatory. I nevertheless couldn’t help but think of all this as a missed opportunity. One alternative approach to providing texts for ephemeral or time-based work may be to offer short videos of interviews and behind-the-scenes time with artists. There are several excellent ones on the exhibition website. Projects like Gray’s or Honda’s or Verabioff’s could have benefited from this type of engaging presentation.

Made in L.A. offers a unique opportunity for an onsite audience to voice a collective opinion by voting for their favorite artist or project. Whenever I was at the Hammer the voting kiosks appeared empty. If people do vote, I wondered, are only the most visually accessible works selected? Buying an expensive exhibition catalog shouldn’t be compulsory. Relating to contemporary art shouldn’t be this difficult.

But ultimately curators Aram Moshayedi and Hamza Walker created a thought-provoking exhibition. Although they eschewed overtly embracing themes, threads do exist that bind the diverse projects together and create a sense of context and continuity. Themes such as: artist as curator or archivist; artist as community activist; artists who critique or celebrate communities; online provocateurs; those who revel in language. The curators sought out artists from wide-ranging creative disciplines. Their focus on cross-disciplinary and community-driven art practices made this biennial consistent and smart. So my vote is cast for best Made in L.A.—with the qualifier that you get back only what you invest in.