Commandeering a mere 180,000 square feet the of the Los Angeles Convention Center’s 760,000, the LA Art Show Modern + Contemporary, resurrected after last year’s COVID cancellation, offers a brief glimpse of the offerings of more than 80 galleries—foreign, domestic, and spendy.

While up-to-the-minute ornaments are understandably present—NFTs (non-fungible tokens for those of us a few minutes behind) and flexing shapes in colorful digital video, there are others that are overexposed to the point of invisibility. A pair of tiny Banksy prints are virtually wallpaper, and a gallery full of Basquiat homages are exactly as vacuous as one might imagine.

At the Rebecca Hossack booth are two elegantly rendered and transparently layered drawings by Nikoleta Sekulovic, large-scale in acrylic and graphite. With an anatomical elegance that nods to the masterful Euan Uglow, a pair of nude female figures look toward and away from the viewer. Opposite these are the oversized book spines of David Morago at Pigment Gallery. Several works, about four-feet tall, are enlarged with horizontal titles that reveal an eclectic library, some volumes are spiral bound while others are clearly graphic novels; an overall tint of age suggests a collector’s obsession.

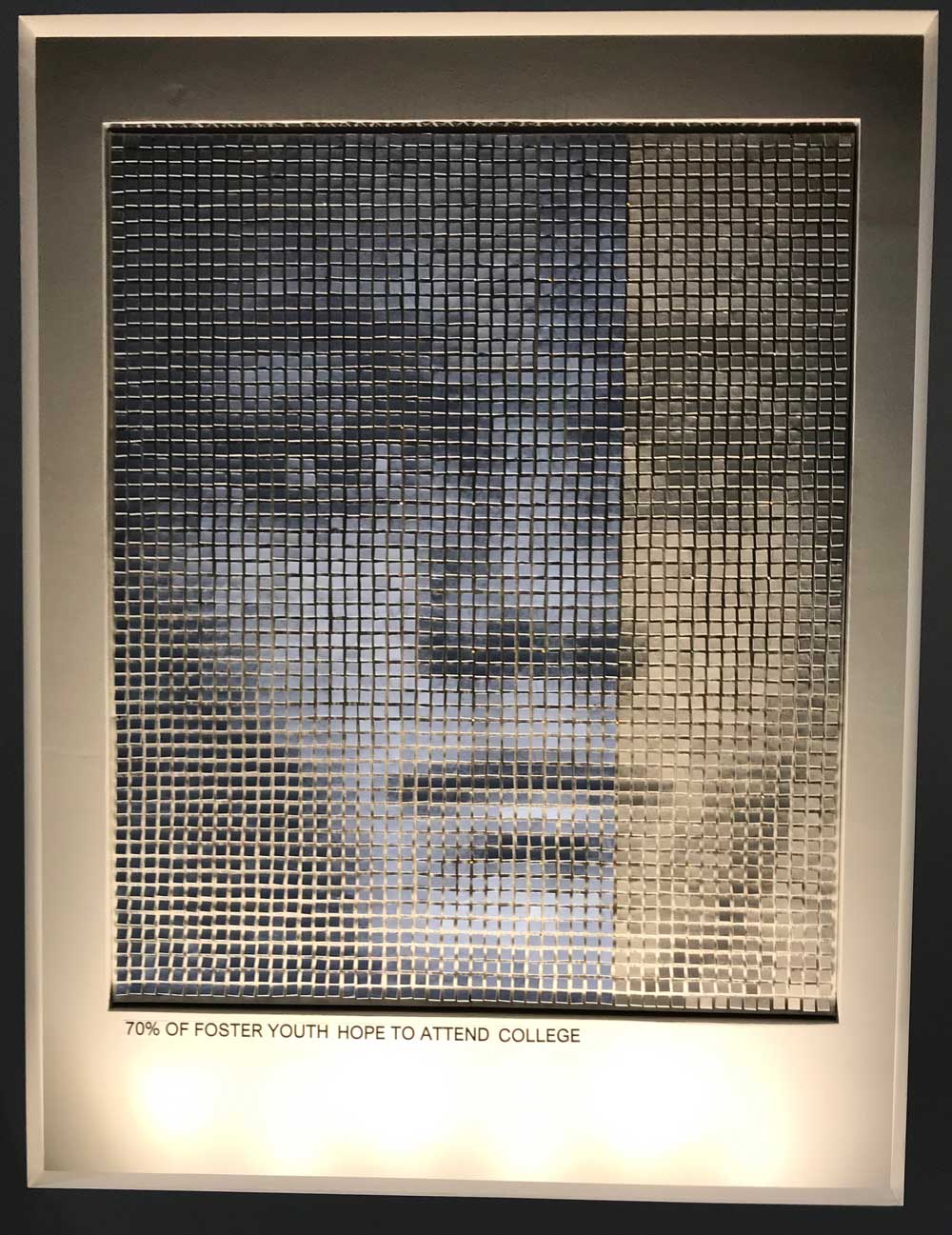

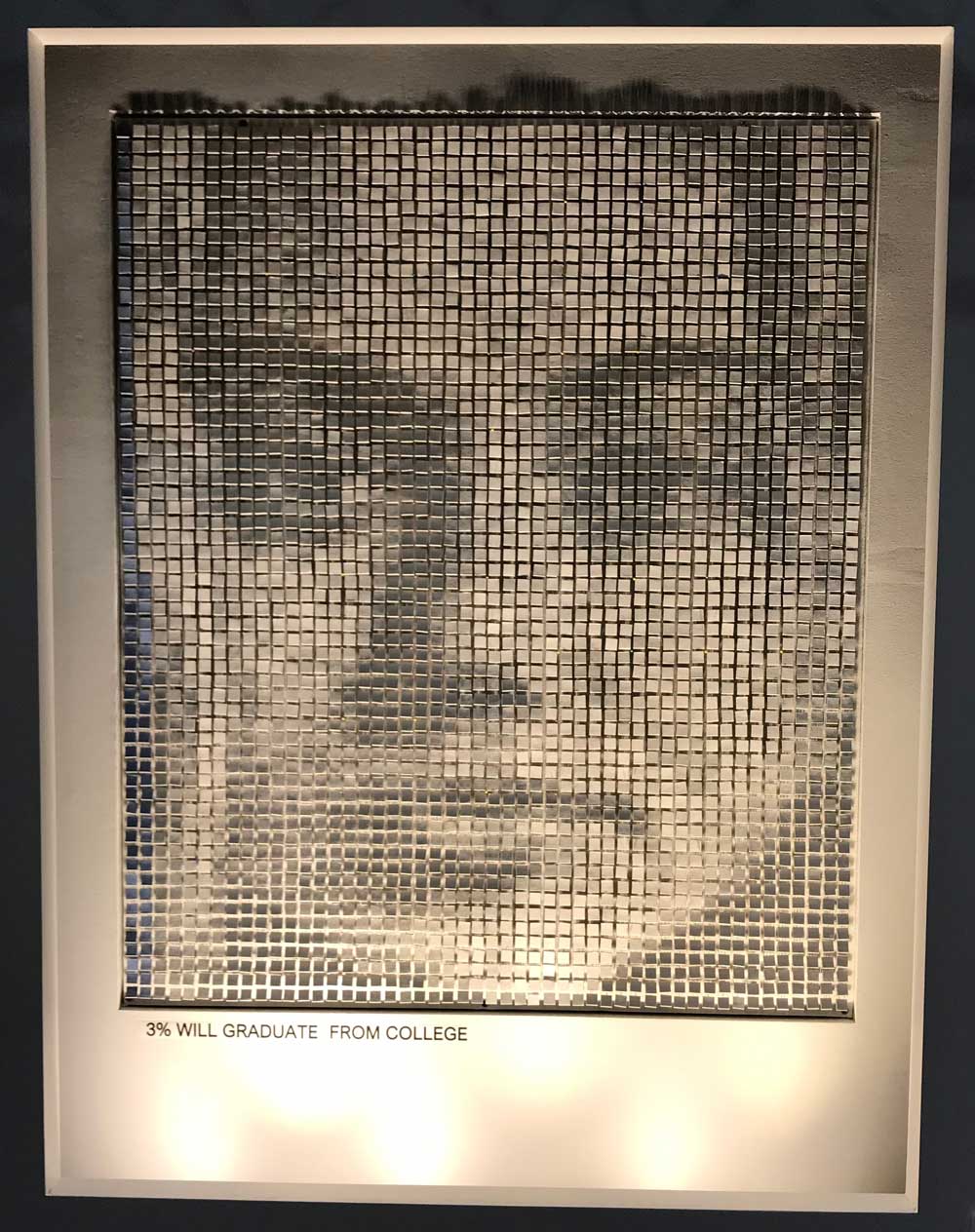

Antoaneta Hillman’s thickly encaustic abstractions, at Cinq Gallery, have the peculiar simultaneity of both age and immediacy. Slathered, scraped, and incised, the works nod to earlier postwar movements while remaining refreshingly current. More accessible viewing can be had at the Beatriz Esguerra booth—graphite and watercolor hauntings of pensive young girls show them with their heads lowered, examining invisible futures. Just south of them are girls and boys in authentic angst at Connect Contemporary, presented in immerging and disappearing split-flap portraits with hopes and consequences underlined. Beneath one portrait reads “70% OF FOSTER YOUTH HOPE TO ATTEND COLLEGE.” Below another, “3% WILL GRADUATE FROM COLLEGE.”

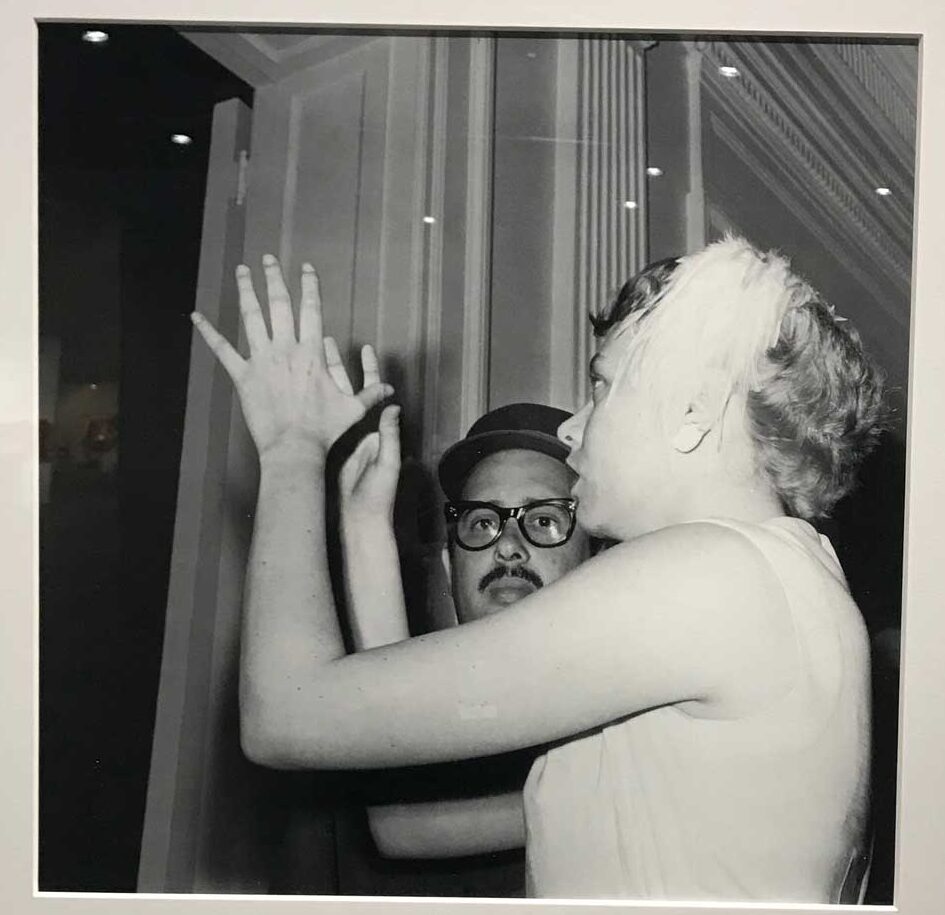

The photographic work of Reynier Leyva Novo at Lisa Sette Gallery is a rich reversal of damnatio memoriae, a traditional tool of tyrants to erase their competitors from history. The young Cuban artist (b. 1983) has turned the tables on the hagiography of Fidel Castro. In a series of old photographs, the artist has erased Fidel; in one image a blind woman attempts to touch the face of the revolutionary hero, she is left grabbing air. In another photo set in a conference room he is literally and figuratively out of the picture—Khrushchev is left talking to an empty chair. Another portrait, this one redemptively transcending the deliberate and racist mistreatment of one of America’s finest athletes, reveals Jack Johnson so ennobled that he appears ready for the Smithsonian. Tim O’Brien’s small painting, more richly and gallantly rendered than either of the Obama portraits, shows the heavyweight champ serene, confident, and fearless. It has the Americana richness of a Grant Wood or Elizabeth Catlett and is a rendering that will endure as a synonym for fighter—an urgent need in these turbulent times.