Do Ho Suh has a career that has yielded exhibitions at Tate Modern, the Serpentine Gallery, the Liverpool Biennial, the Gwangju Biennale, a retrospective show at the Seattle Art Museum, and the Venice Biennale where he represented his native South Korea. His practice is quite successful, in part because it is a revelatory prism through which to attend the great themes of art and humanities inquiry: home, space, history, (cultural) displacement, the body and monuments.

His piece at the Venice Biennale, Some/One (2003) consisted of an emperor’s vast and glittering robe comprised of thousands of soldiers’ dog tags. Another work, Floor (1997–2000), was formed of a room full of translucent floor tiles held up by a legion of tiny, human-shaped plastic figures bearing the weight of the gallery’s visitors. These works used the strategy of overwhelming accumulation to make the intuitive claim of our individuality seem both brittle and poignant.

However, in the last few years he has latched onto the idea of home, doggedly reworking it. Several other large installations, including “Home Within Home” (2009–11), “Net-Work” (2010) and “Fallen Star” (2012), follow this theme, seemingly examining the home as an architectural container for the self and simultaneously contained by the self. Suh’s obsessiveness with this theme is starkly manifested in his September show, “Rubbing/Loving Project” (2014) at Lehmann Maupin, with two simultaneous exhibitions in their galleries in Chelsea and on Chrystie Street, titled “Do Ho Suh: Drawings.”

Do Ho Suh Rubbing/Loving Project: Metal Jacket, 2014, Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

The Chelsea space featured Rubbing/Loving Project, 348 West 22nd Street, a recreation of elements of Suh’s former Manhattan apartment where entire walls and large fixtures—including doorknobs, wall sconces, telephone jacks, faucet handles, towel bars and smoke alarms—were enveloped in vellum and traced with pencils into a state of quasi-being by Suh and a crew of assistants. The main space showed the pieces done in blue-pencil and displayed them flat: tacked to a wall or laid out on the ground. These impressions were made on vellum, a spectral medium that holds the image transferred onto it, but being partially translucent, made the images float. When walking among these blue deflated forms undulating with the wind, one felt the gallery infused with lamentation. However, the works at the Chrystie location (representing structures in Gwangju, Korea) were far less compelling because the rubbings were affixed to actual structures. Thus they read simply as documentation of his process with a video showing the operation emphasizing this view.

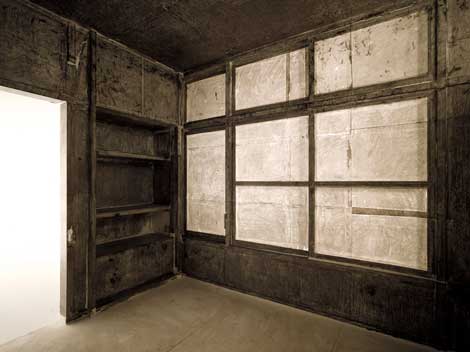

Do Ho Suh, Rubbing/Loving Project: Company Housing of Gwangju Theater, 2012 Commissioned by Gwangju Biennale 2012 Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

One feels safe waking in the dark knowing where the light switch is, but the loss of this familiarity does not seem so traumatic as to justify this keening memorialization. Since Suh actively avoids settling in one home—maintaining residences in London, Seoul and New York—this work begs to be read psychologically. It is nostalgic, but only in the term’s literal translation: the pain of home. The home haunts Suh—perhaps in its pliability, its refusal to remain solid and fixed. The repetition in his practice of this type of work suggests the unconscious recreation of a childhood trauma. Perhaps the home did not remain where he last left it. The vellum seems an apt analogy for the artist: the heavily imprinted, floating signifier.

Do Ho Suh: DRAWING 201 Chrystie Street, New York Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Suh undoubtedly will continue to trace the circuits that these great, insoluble themes have made in his psyche and being, reifying them, physicalizing them, making them monuments of self-articulation. One wonders what happens to Suh’s practice if the wounds he carries with him ever heal, or become less enthralling to explore. That likely will not occur because, at this stage, his practice has become coextensive with how he contemplates and faces new challenges—really an extension of him feeling his way through the dark.