With eight new oil-and-enamel paintings, Kirsten Everberg continues her practice of exploring filmic images as a means of exercising her interest in perception, memory and narrative. Visually, her paintings present an eerie absence. In Everberg’s hands, film scenes are stripped of human presence, and she creates works that appear like empty stage sets or unsettling simulacra. Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1975 film Mirror, the nexus of Everberg’s new work, proceeds with a loose narrative structure and imagines the life of the film’s mostly unseen protagonist as a series of fleeting memories and impressions.

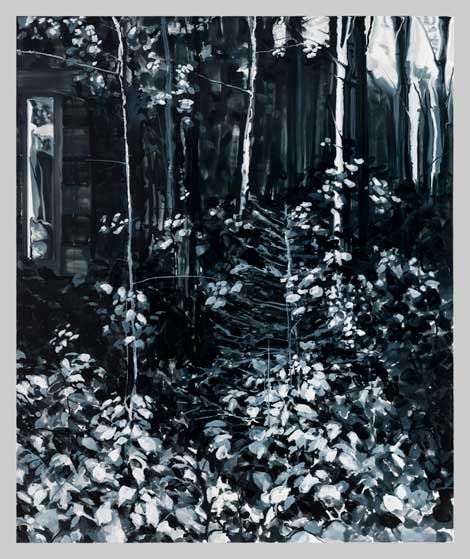

Everberg echoes Tarkovsky’s fascination with the shifting locus of memory and the blurring of reality with dreams as she mixes and reshuffles , juxtaposing multiple splices into synthesized representations. More signifiers than worlds onto themselves, her paintings offer entry into the limitless speculative possibilities encountered in Mirror. Everberg’s Come to Tomshino (Mirror) (2013) echoes a line spoken by a character who makes one brief appearance, musing enigmatically about roots and the perceptive capacity of plants.

Early this year, with four new paintings and drawings based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 masterpiece, Rashomon, Everberg explored similar territory with “In A Grove,” part of the project series at the Pomona College Museum. “Grove” placed the viewer squarely in the shoes of Kurosawa’s characters, as if seeing the forest through their eyes. What vivified this conceit was the paintings’ spatial ambiguity, which mirrored the elusiveness of the film’s narrative and the disorienting camera work of the forest scenes. Similarly, the paintings at 1301PE seem to place the viewer inside Everberg’s transmutation of Tarkovsky’s film, yet the presence of recognizable cues—a chair, a window or French door—eliminates the kind of shifting perspective that was so entrancing in her “Grove” exhibition.

Where Everberg’s painting is most successful, she abandons the structural rigidity of architecture as the support of her image and lets her paint mix and run, as it commingles in washes and colors coagulate, and where she allows for chance, setting up rivulets, color bleeds and capillary action. What was successful about “Grove” is also true for her treatment of The Mirror: the way her paintings at the Pomona College Museum danced between representation and abstraction fed Everberg’s paintings into a self-reflexive loop as convincing self-contained worlds, which strengthened the paintings as an analog to viewing Kurosawa’s film—or at least evoking the memory of it.

Without knowledge of her reference to Tarkovsky, the paintings become mysterious in a way that attenuates engagement. As much as Everberg promotes a conceptual link between her painting and the artifice of narrative and film, suggesting that the way we reinterpret, interpose and represent events, replaying them and examining them endlessly into the future is critical to our perspective on painting, in this case, it is the visual and tactile depth of her surfaces that allows us to suffuse the tide of mental elaboration with the sensuality of experience, as the paint runs and flows into a tidal basin of thought.