I threw a bit of ink (or the digital equivalent) around the topic of LACMA in the last post—its fabulous summer of art exhibitions, its fabulous trustees and director, and their plans for an even more fabulous east campus—perhaps inspired by that solar swimming pool Peter Zumthor has dreamed up for it. But regardless what takes shape there, one thing that won’t change is that slightly alien vessel designed by Bruce Goff and perched across from the Calder Quintains and the Bing Theatre. The Pavilion for Japanese Art may not always work perfectly as an exhibition space; but it is one of the most serene and perfectly lit spaces in the entire museum complex and never less than a pleasure to visit.

The current exhibition (up through October 19, 2014), Kimono for A Modern Age, is a case in point. Arranged in groups of three (all drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, and curated by Sharon Takeda) beginning on the upper level and descending along the ramp that spirals to the lower level, the viewer is occasionally positioned obliquely at a slightly awkward distance from the garments. The viewer can stop and move a bit closer behind the handrail, but the perspective and moment’s balance, the flow of the ‘narrative’ (which is not strictly chronological) is interrupted.

The current exhibition (up through October 19, 2014), Kimono for A Modern Age, is a case in point. Arranged in groups of three (all drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, and curated by Sharon Takeda) beginning on the upper level and descending along the ramp that spirals to the lower level, the viewer is occasionally positioned obliquely at a slightly awkward distance from the garments. The viewer can stop and move a bit closer behind the handrail, but the perspective and moment’s balance, the flow of the ‘narrative’ (which is not strictly chronological) is interrupted.

Still it doesn’t really matter because we hardly need to be persuaded to take a step back up the ramp for a closer look at these kimono. Designed and made between the late 19th century to mid-20th century, unlike their prototype garments, the kimono of the aristocracy (itself a slightly streamlined day/evening-wear rendition of the elaborate formal dress of the imperial court—in effect, a Japanese haute couture, governed by centuries of tradition, sumptuary custom and regulation), which were cut from heavy silk damasks and brocades, richly hand-embroidered, dyed and often painted, these kimono were constructed from silk crepe or plain-weave silk woven on industrial looms, and dyed and patterned using the stencil and rice-paste resist method known generally since the late 17th century as yuzen and further adapted to industrialized dyeing and printing processes. (Most of these kimono are described as ‘heiyo + kasuri’ meisen (plainweave silk), which I assume means that warp and weft twills or threads are separately stenciled before finally woven into the finished bolt of fabric. (The evolution of the design and manufacturing processes of these textiles and garments is rich and fascinating, criss-crossing east Asia and the Silk Route, but beyond my scope here.)

Still it doesn’t really matter because we hardly need to be persuaded to take a step back up the ramp for a closer look at these kimono. Designed and made between the late 19th century to mid-20th century, unlike their prototype garments, the kimono of the aristocracy (itself a slightly streamlined day/evening-wear rendition of the elaborate formal dress of the imperial court—in effect, a Japanese haute couture, governed by centuries of tradition, sumptuary custom and regulation), which were cut from heavy silk damasks and brocades, richly hand-embroidered, dyed and often painted, these kimono were constructed from silk crepe or plain-weave silk woven on industrial looms, and dyed and patterned using the stencil and rice-paste resist method known generally since the late 17th century as yuzen and further adapted to industrialized dyeing and printing processes. (Most of these kimono are described as ‘heiyo + kasuri’ meisen (plainweave silk), which I assume means that warp and weft twills or threads are separately stenciled before finally woven into the finished bolt of fabric. (The evolution of the design and manufacturing processes of these textiles and garments is rich and fascinating, criss-crossing east Asia and the Silk Route, but beyond my scope here.)

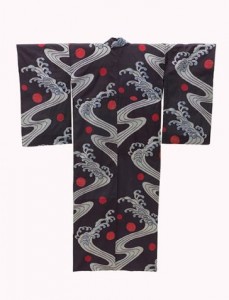

What’s immediately striking is just how contemporary the design of these garments looks. To judge simply from the designs and all-over patterns, these prints might have been executed anywhere from the latter part of the 20th century to today. (Memo to Pucci: Catch up!) The boldly expressive graphic lines, hard-edge abstract geometrics wedded to an adventurous palette, and optical effect geometries, stylized or abstracted representational patterns (sometimes in a demotic/schematic style that might have been drawn from painting of the last 15 years) not only pace the Western avant-garde, but leap ahead of it by a generation or more.

What’s immediately striking is just how contemporary the design of these garments looks. To judge simply from the designs and all-over patterns, these prints might have been executed anywhere from the latter part of the 20th century to today. (Memo to Pucci: Catch up!) The boldly expressive graphic lines, hard-edge abstract geometrics wedded to an adventurous palette, and optical effect geometries, stylized or abstracted representational patterns (sometimes in a demotic/schematic style that might have been drawn from painting of the last 15 years) not only pace the Western avant-garde, but leap ahead of it by a generation or more.

The non-chronological progression of the show emphasizes the bilateral aspect of the cultural exchange between Japan and Western Europe. Although we’re familiar with the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e prints on Van Gogh and the Post-Impressionists (as well as textile and garment design on contemporaneous fashion), it seems clear that these art currents reverberated into the East. From the Nabis through Cubism and later derivative post-Cubist movements (most prominently, the Orphism of Robert Delaunay and the art and textile design of Sonia Delaunay, but also Purism) there was an uncanny synchronicity among contemporaneous art and design ideas and impulses in both Japan and the West. Although only one example here directly acknowledges the influence of the Delaunays, there are kimono here that echo or anticipate everything from Expressionism, Cubism and De Stijl to post-painterly abstraction, to hard-edge geometric abstraction (e.g., Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin) to post-Op and post-Pop styles as diverse as Stella, Noland, Lictenstein, Bridget Riley, and still more contemporary styles. Among the highlights (besides the misty autumnal prisms of the ‘Delaunay’ kimono): a fractalized starburst design in blue and white with hints of yellow at the center that evokes the rising sun flag of pre-war Japan; a quasi-Pointillist butterfly patterned kimono; ‘watermelon’ quarter-discs that remind me a bit of Leger; candy-colored striped semi-discs that evoke both Stella and mille-fiori paperweights; a dancing double-helix design in lavender with touches of red and yellow; stylized cresting wave designs both Expressionistic and geometric; linear ‘streamline moderne’ patterns; and graphic and calligraphic prints evoking styles from Mondrian to Cy Twombly.

The non-chronological progression of the show emphasizes the bilateral aspect of the cultural exchange between Japan and Western Europe. Although we’re familiar with the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e prints on Van Gogh and the Post-Impressionists (as well as textile and garment design on contemporaneous fashion), it seems clear that these art currents reverberated into the East. From the Nabis through Cubism and later derivative post-Cubist movements (most prominently, the Orphism of Robert Delaunay and the art and textile design of Sonia Delaunay, but also Purism) there was an uncanny synchronicity among contemporaneous art and design ideas and impulses in both Japan and the West. Although only one example here directly acknowledges the influence of the Delaunays, there are kimono here that echo or anticipate everything from Expressionism, Cubism and De Stijl to post-painterly abstraction, to hard-edge geometric abstraction (e.g., Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin) to post-Op and post-Pop styles as diverse as Stella, Noland, Lictenstein, Bridget Riley, and still more contemporary styles. Among the highlights (besides the misty autumnal prisms of the ‘Delaunay’ kimono): a fractalized starburst design in blue and white with hints of yellow at the center that evokes the rising sun flag of pre-war Japan; a quasi-Pointillist butterfly patterned kimono; ‘watermelon’ quarter-discs that remind me a bit of Leger; candy-colored striped semi-discs that evoke both Stella and mille-fiori paperweights; a dancing double-helix design in lavender with touches of red and yellow; stylized cresting wave designs both Expressionistic and geometric; linear ‘streamline moderne’ patterns; and graphic and calligraphic prints evoking styles from Mondrian to Cy Twombly.

What is equally striking is how lightly and gracefully these very traditional Japanese garments bear their Western influences or reflect similar affinities. I found myself drawn back to the literature of Sei Shōnagon and Lady Murasaki, with their acute enveloping sense of the natural world and its resonance with court life—as well as the ceremonial styles of dress that celebrated their passage through it. Just as the written language of the imperial court was a kind of poetry (and as rigorously judged), there is a dual quality of precision and poetic compression here that both emphasizes the modernity of the design and integrates it organically into the precise cut, folds and drapery of the kimono. There’s a perspective here that bears closer consideration—an attitude towards both self and environment. We’ve lost something of this dual sense of organic evolution and diurnal ceremony as we’ve laid waste to the natural world. Kimono for A Modern Age offers us a few golden moments in which to reclaim that perspective.

What is equally striking is how lightly and gracefully these very traditional Japanese garments bear their Western influences or reflect similar affinities. I found myself drawn back to the literature of Sei Shōnagon and Lady Murasaki, with their acute enveloping sense of the natural world and its resonance with court life—as well as the ceremonial styles of dress that celebrated their passage through it. Just as the written language of the imperial court was a kind of poetry (and as rigorously judged), there is a dual quality of precision and poetic compression here that both emphasizes the modernity of the design and integrates it organically into the precise cut, folds and drapery of the kimono. There’s a perspective here that bears closer consideration—an attitude towards both self and environment. We’ve lost something of this dual sense of organic evolution and diurnal ceremony as we’ve laid waste to the natural world. Kimono for A Modern Age offers us a few golden moments in which to reclaim that perspective.