This article originally appeared in our November/December 2008 issue on Everyday Politics:

Nov/Dec 2008 Artillery cover.

In a text written for this show and displayed on one of the gallery walls, Kerry James Marshall says “I am working on paintings that address the theme of LOVE.” “Love” is less a theme than a pretext for Marshall’s real subject, which is history. There is nothing of the “idyll” in any of these paintings — and “wistful” is not a word that can be easily attached to their calculated bits of romantic fancy. At the risk of sounding either latently racist or completely loony, as I was looking at the paintings, a line from an old Sondheim show tune ran through my head: “Liaisons – what’s happened to them?”

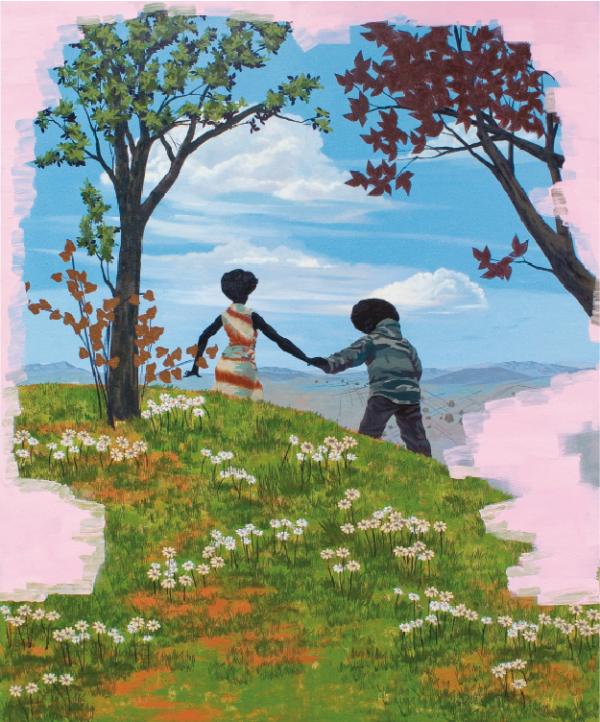

Like the undercurrent of disillusionment and desperation that runs just beneath the flirtation and frolic of the Bergman/Sondheim vehicle, there is a kind of sadness and not a little anger beneath these “Rococo” motives (e.g., a woman’s body sinuously stretched out in the grass of a clearing — singly or in a couple; a couple hiking or chasing over a dune or hilltop) that, today, are a stock of kitsch imagery. Marshall alludes to the kitsch in the more schematic passages of his “pastoral” settings (fields and bluffs of grasses and wildflowers). Marshall conveys a kind of impatience through abstraction — or obliteration — for his own apparent pseudo-nostalgia. The landscapes aren’t lost in the miasma of gossamer fabrics and the rosy filtered light of wooded parkland or sunsets, but deliberately whittled away at the edges, brushed out in broad, flat pink strokes. This is about historical revisionism and displacement; also, simply power.

Africans or (African-French) don’t begin to appear in French painting until approximately the early 19th century. They appear somewhat earlier in Italian and Spanish painting in the late Renaissance. So what? How many Africans were there in France at the time? And just how many Africans made it to the European royal courts — where these paintings took their inspiration — anyway? Inspiration might be overstating it. The kind of pastoral fantasy worked by Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher was exactly that. It was sheerly escapist fare even for the aristocracy for whom it was intended. The vast majority of white provincial French people were similarly closed off from this world.

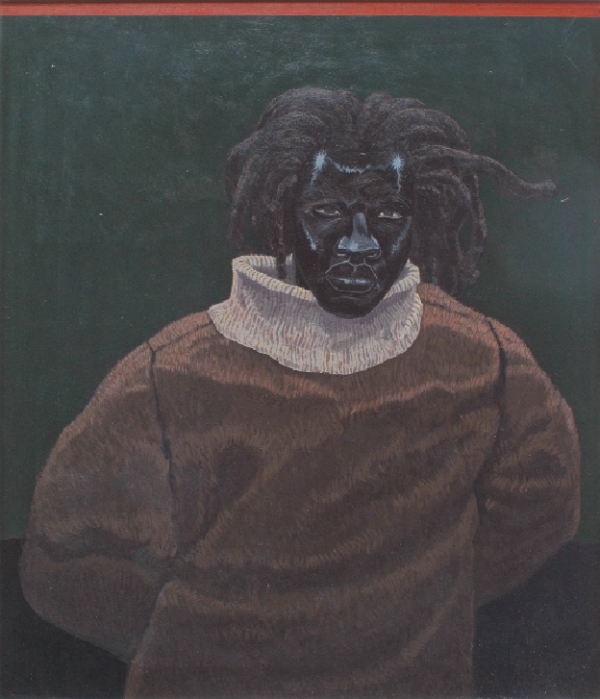

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of John Punch (Angry Black May 1646), 2008.

Even before we view Marshall’s “love” pastorales, though, we have a sense of this confrontation with Eurocentric ideals of beauty or nobility in a series of portraits hanging in the front gallery. They’re formal portraits of beautiful people. One, a proud, somber, distinctly African and very black face sporting a thick mane of dreads, in a sable-colored sweater has a lion’s bearing that has nothing to do with the over-sized cowl neck of his sweater. African or not, this could be the mien of an Elizabethan lord — or conceivably an urban intellectual from anywhere.

Directly across from this portrait is another, somewhat angrier, lordly black man, this one swagged in gold chains — much as he would have been had he been painted by, say, Titian. Titian never painted a black aristocrat, but he might have if there were any to be found in Venice.

Marshall is doing more here than simply confronting European notions and traditions, though. He’s claiming them for his own — which, as for any late 20th- to 21st-century American artist, they are. But is there really a point to photoshopping (in painterly fashion) black people in or “pink-washing” the fantasy out? It’s as if Marshall wants a rewrite of art history. Africans are noticeably absent from European painting until well into the 19th century — an implacable historical fact that is pointless to argue with.

Marshall’s portraits are undeniably beautiful; but the most interesting work here by far are the comic panels in the last gallery from Marshall’s “RHYTHM MASTR” series — a very contemporary order of cultural and historical confrontation — where past and present collide in the kind of gritty, multi-cultural, polyglot urban tide pools ubiquitous in cities like Los Angeles. In one panel, a voodoo idol or ceremonial figure is seemingly conjured by a contemporary figure in the foreground with a bongo drum. In another, titled Ho’s Stroll, the sense of anywhere/everywhere is explicit: “What is this place?” A cloud of Asian characters issue from a van, while the protagonist takes on the 20th century: “If Lincoln supposta freed our asses in 1865, why the fuck was we gittin our heads cracked tryin to vote, in 1965?” This is where it gets interesting: at the divide (or not) between cultural and political disenfranchisement. Why do I have the feeling we’ll be asking similar questions this year in states like Ohio and Florida?

Kerry James Marshall: PORTRAITS, PIN-UPS And Wistful Romantic Idylls, Exhibition Dates: September 6- October 24, 2008, at Koplin Del Rio, Culver City, CA. Images courtesy Koplin Del Rio Gallery, Culver Ctiy, CA